The Oldest Cookbooks From Libraries Around the World

Vintage recipes include flaming peacocks and kangaroo brains.

For as long as libraries have been repositories of wisdom and knowledge, there has been a place on the shelf for cookbooks. In fact, many early cookbooks were more than just recipe collections—instructions for concocting medicine often jostled with dinner ideas for page space. Atlas Obscura has previously displayed ancient recipe collections, such as the Yale Peabody Museum’s Babylonian tablets, which contain the oldest known recorded recipes, and the New York Academy of Medicine’s 9th-century De re culinaria, the oldest surviving cookbook in the West.

Cookbooks were once intended mainly for upper-class households. Only relatively recently did printing and educational advances make them more democratic. Today’s versions tend to hold well-lit photographs and elegant prose. But humanity has long turned to cookbooks for inspiration and entertainment, and whether sauce-stained or Gothic-lettered, cookbooks offer glimpses of humanity’s food history. Here is a collection of some of the oldest cookbooks from libraries around the world.

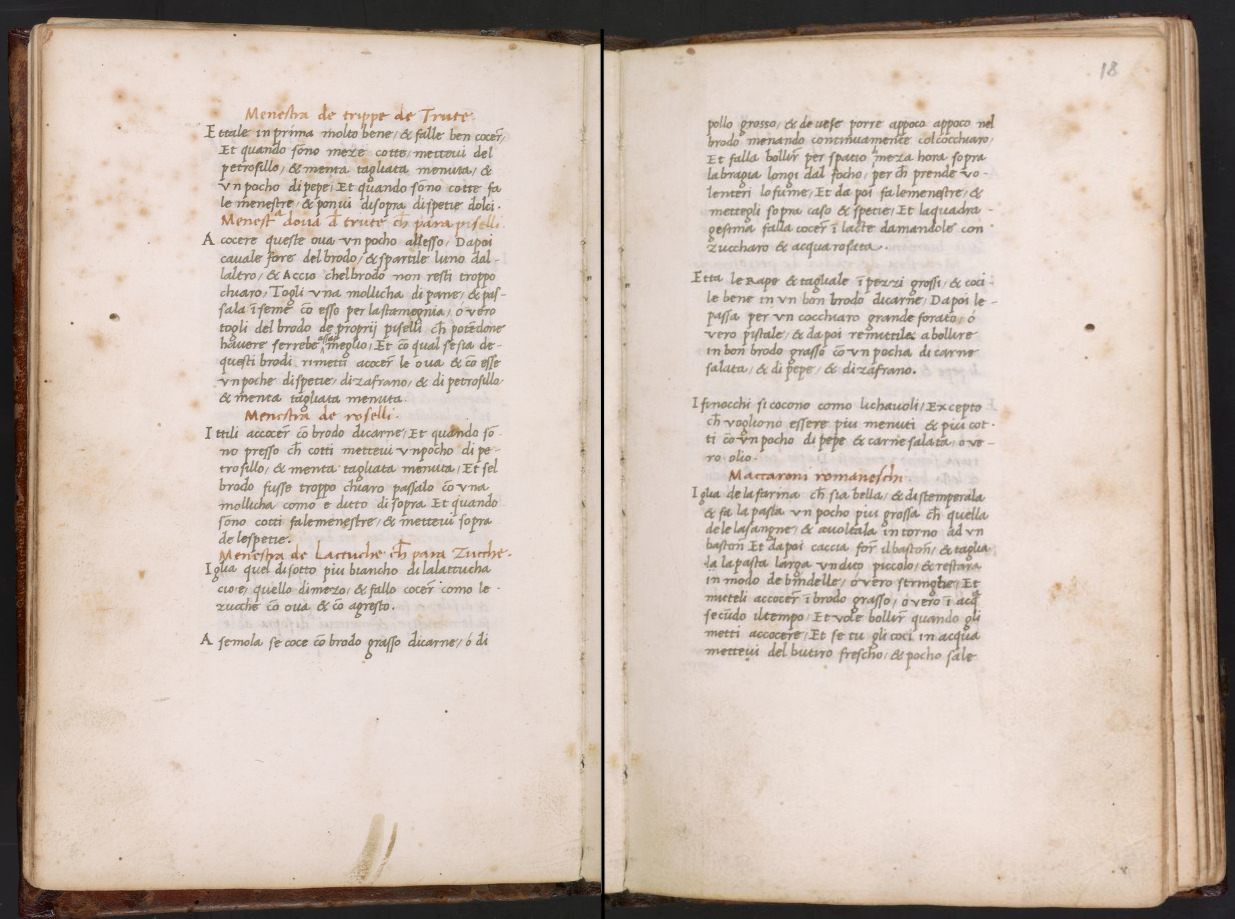

Libro de Arte Coquinaria

The Library of Congress

The 15th-century Libro de arte coquinaria, or The Art of Cooking, is the work of Maestro Martino of Como, chef to a famous cardinal. Martino was known for cooking lavish banquets for his employer. Along the way, he achieved fame as “the prince of cooks.” Martino likely deserves the title, according to Brett Zongker from the Library of Congress, since his Libro “is the first known book to specify ingredients, cooking times, techniques, utensils, and amounts.”

As a late medieval chef cooking on the cusp of the Renaissance, Martino includes a recipe for everything from almond-rice pudding to “How to Dress a Peacock With All Its Feathers, So That When Cooked, It Appears to Be Alive and Spews Fire From Its Beak.” He also recommends that chefs boil eggs for the amount of time needed to recite the Lord’s Prayer: around two minutes.

Martino’s work is momentous for another reason too: In the 15th century, his recipes made up a major part of the world’s first printed cookbook, Platina’s De honesta voluptate et valetudine. A scribe practiced calligraphy on one of the last pages of this particular volume.

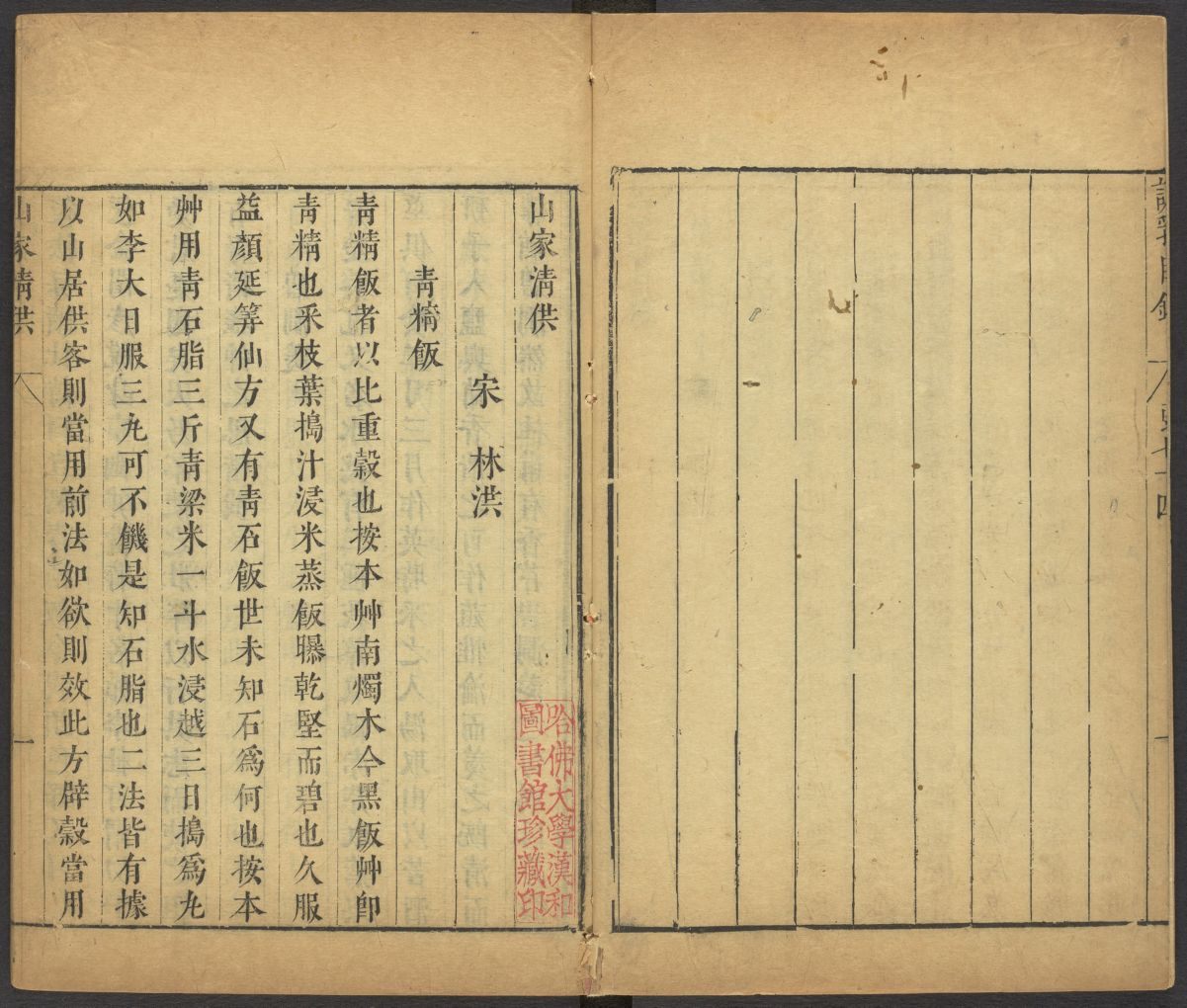

Shanjia Qinggong

The Harvard-Yenching Library

The Harvard-Yenching Library owns a 17th-century copy of the Simple Offerings of Rural Households (Shanjia qinggong, 山家清供). Containing over 100 recipes and many food-related anecdotes, Simple Offerings is probably the earliest surviving cookbook in Chinese. The author, Lin Hong, was a man of letters who lived in the mid-13th century. Lin evidently preferred vegetarian foods, as most of his recipes are plant-based.

He recorded instructions for making fragrant porridges that blended grains with rose-leaf bramble and cakes from pine pollen. There’s also a recipe for vegan “lung.” As translated by Robban Toleno, to make this mock offal: “Collect together bean starch, deep-fried dough, sesame, pine nut, walnut. Remove skins. Add a little dill, white sugar, a little ‘red ferment’ [yeast] ground into powder. Mix it together, put it in a rice pot, and steam until cooked. Cut it to appear like pieces of lung and serve it with a spicy sauce.”

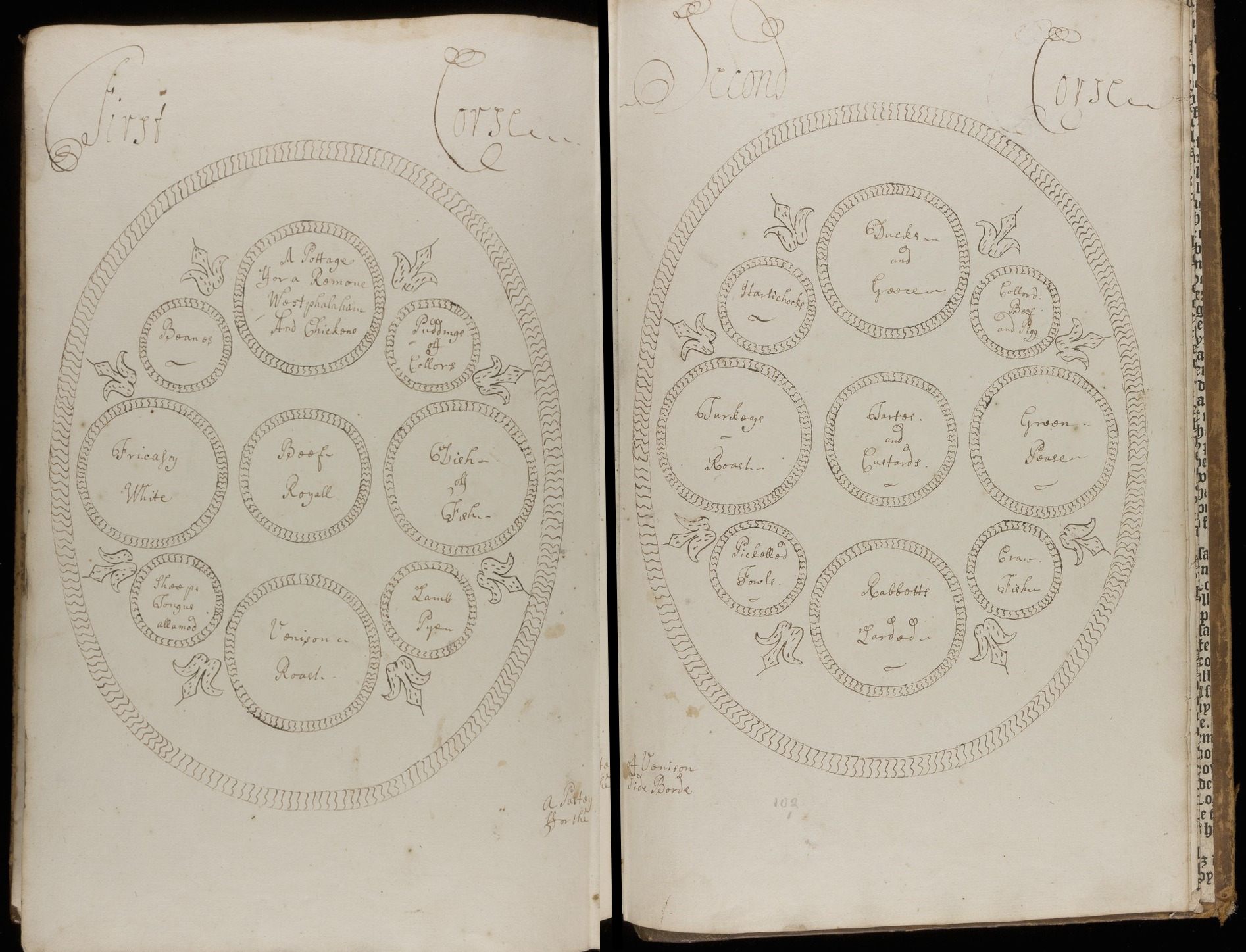

Untitled Manuscript

Beinecke Library

Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library contains this handwritten manuscript cookbook from the 1750s. According to the library, the recipes include everything from medicinal “plague water” to chocolate puffs. The manuscript has 14 sections and 502 recipes for various meats, sweets, and preserves. Its endpapers were recycled from a 16th-century bible. Little is known about the provenance of the manuscript, which the library purchased in 2007.

According to archivist Diane Ducharme, a bookplate in the front of the book bears the symbol of the Martin family, who lived at the appropriately-named Ham Court in the 18th century. “It would have been originally used in a family of similar or superior status,” she writes, “as the sample bills of fare are for the ambitious multi-course meals served at dinner parties and entertainments.”

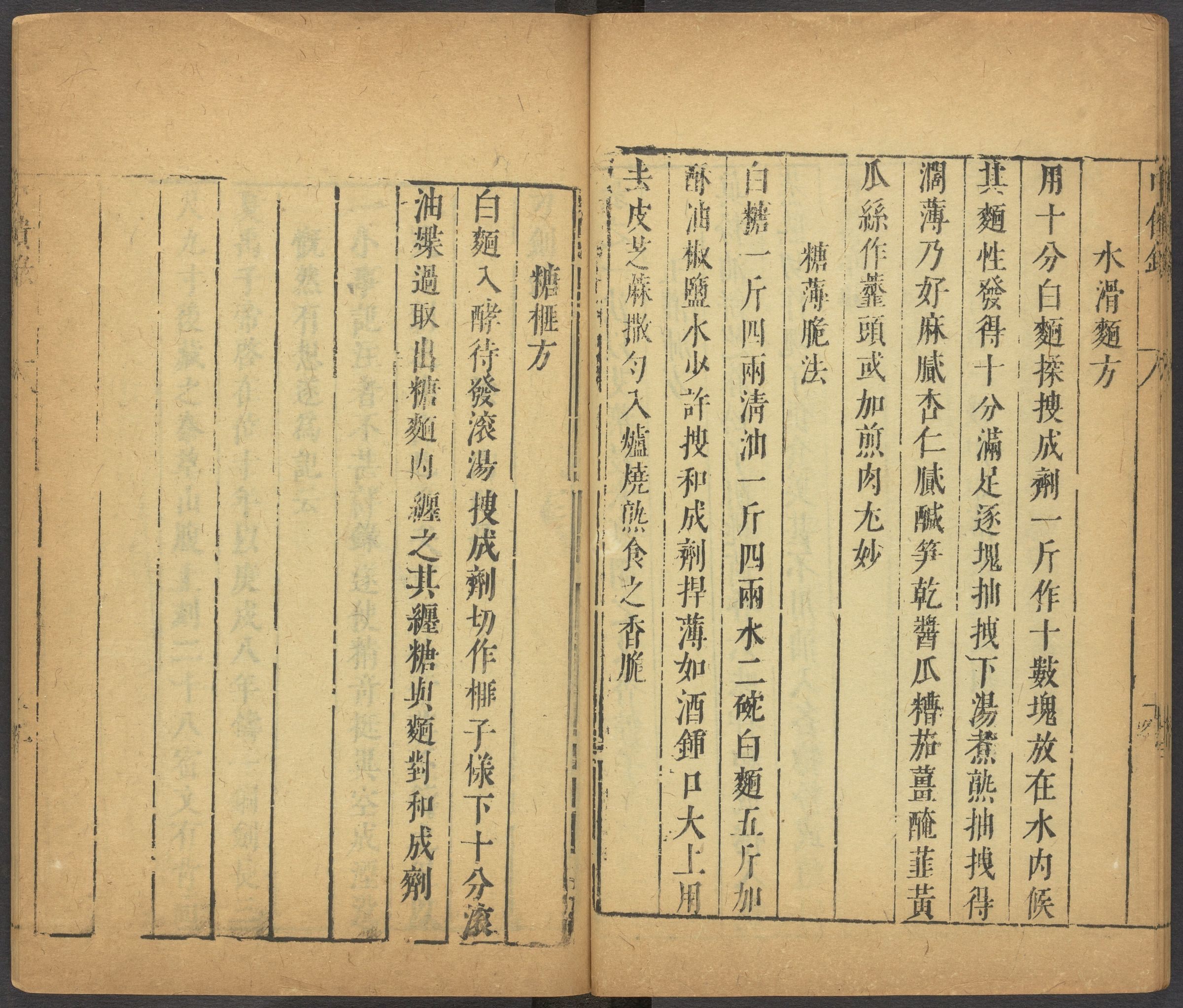

The Cooking Manual of Madame Wu

The Harvard-Yenching Library

Harvard-Yenching is also home to a 17th-century copy of the Cooking Manual of Madame Wu (Wushi Zhongkui lu, 吳氏中饋錄), one of two surviving cookbooks by a Chinese woman before the 20th century. Unfortunately, few of Madame Wu’s personal details are known. Scholars conjecture that she lived in the larger Shanghai region during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279). Regardless, Cooking Manual offers a wealth of information about everyday eating in the Song Dynasty, with recipes for pickled daikon, dried bamboo shoots, meat jerky, and wontons.

Madame Wu apparently had a weakness for sweets, as she devoted a full chapter of her cookbook just to desserts. According to translator Sean Chen, the chapter has “quite a few food items that have Middle Eastern or Central Asian influences.” These include treats similar to halva, jalebi, and samosa, and a buttery crisp that resembles the modern Syrian bazarek. To prepare the crisp, combine sugar, vegetable oil, water, flour, ghee, and spiced salt. Roll out the dough thinly, cut into circles with a small beer cup, sprinkle on sesame seeds, and bake in an oven until “fragrant and crispy.”

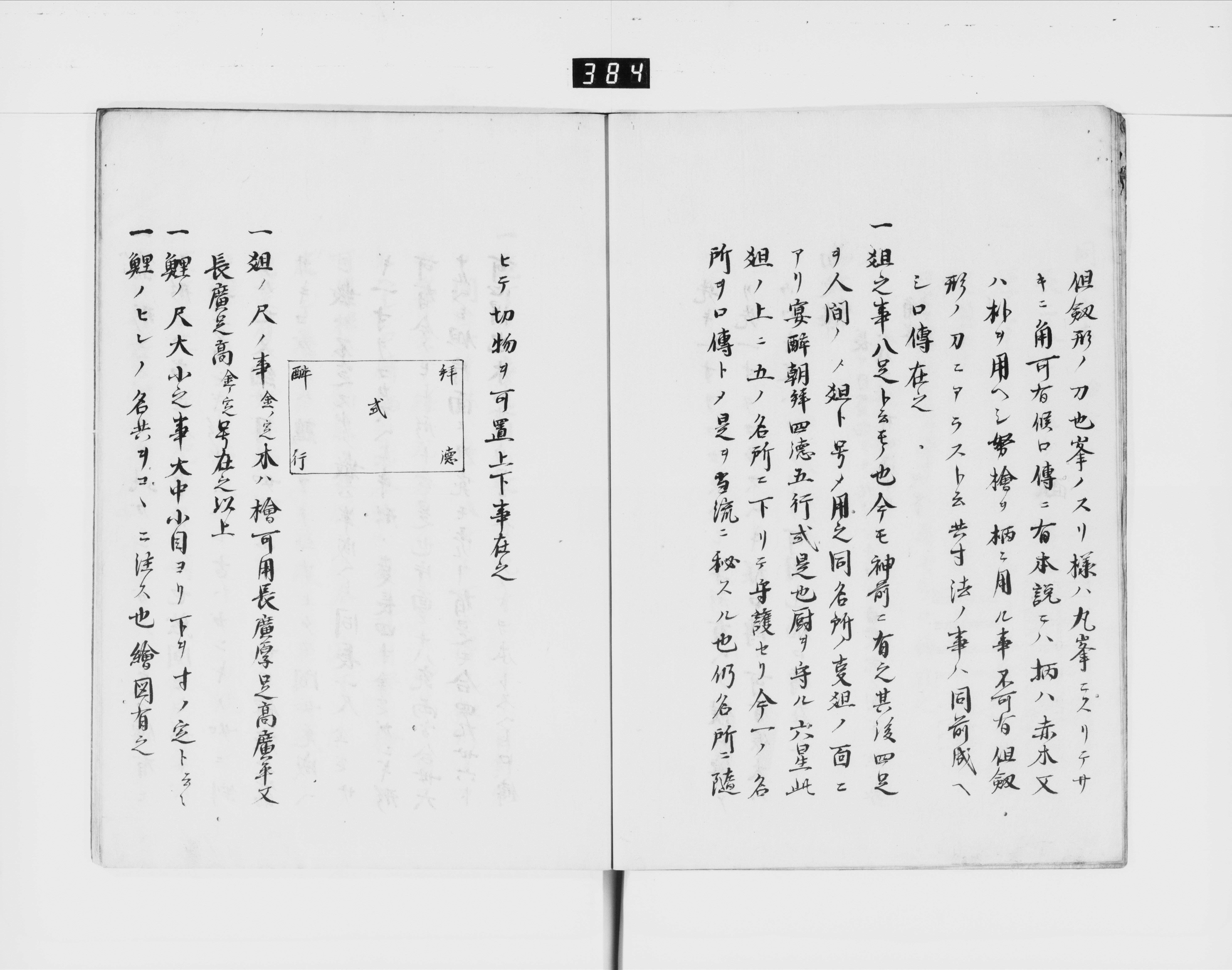

Shijōryū Hōchō Sho

Osaka University Library

The Osaka University Library holds Japan’s oldest surviving cookbook, the Shijō School Text on Food Preparation (Shijōryū hōchō sho, 四條流包丁書), which dates to 1489. The manuscript is written in fluid Japanese calligraphy by an unknown professional chef, or a hōchōnin (“man of the carving knife”). At those banquets, hōchōnin wowed the shogun and other honored guests with their knife skills, and turned seafood and fowl into decorative art with nine-inch blades. One of their favorite mediums was spiny lobster, which the hōchōnin would cut and present in the shape of boats.

The preparation and presentation of seafood occupies a lot of space in the Shijō School Text. The medieval author, for example, emphasized proper vinegar pairings when preparing sashimi. He recommended wasabi vinegar for carp, ginger vinegar for sea bream, and smartweed vinegar for sea bass. There were other recipes in the hōchōnin’s repertoire, including miso soup served with raw crane meat and lichen. But don’t expect to see this combination on menus in Japan today. It disappeared from tables centuries ago.

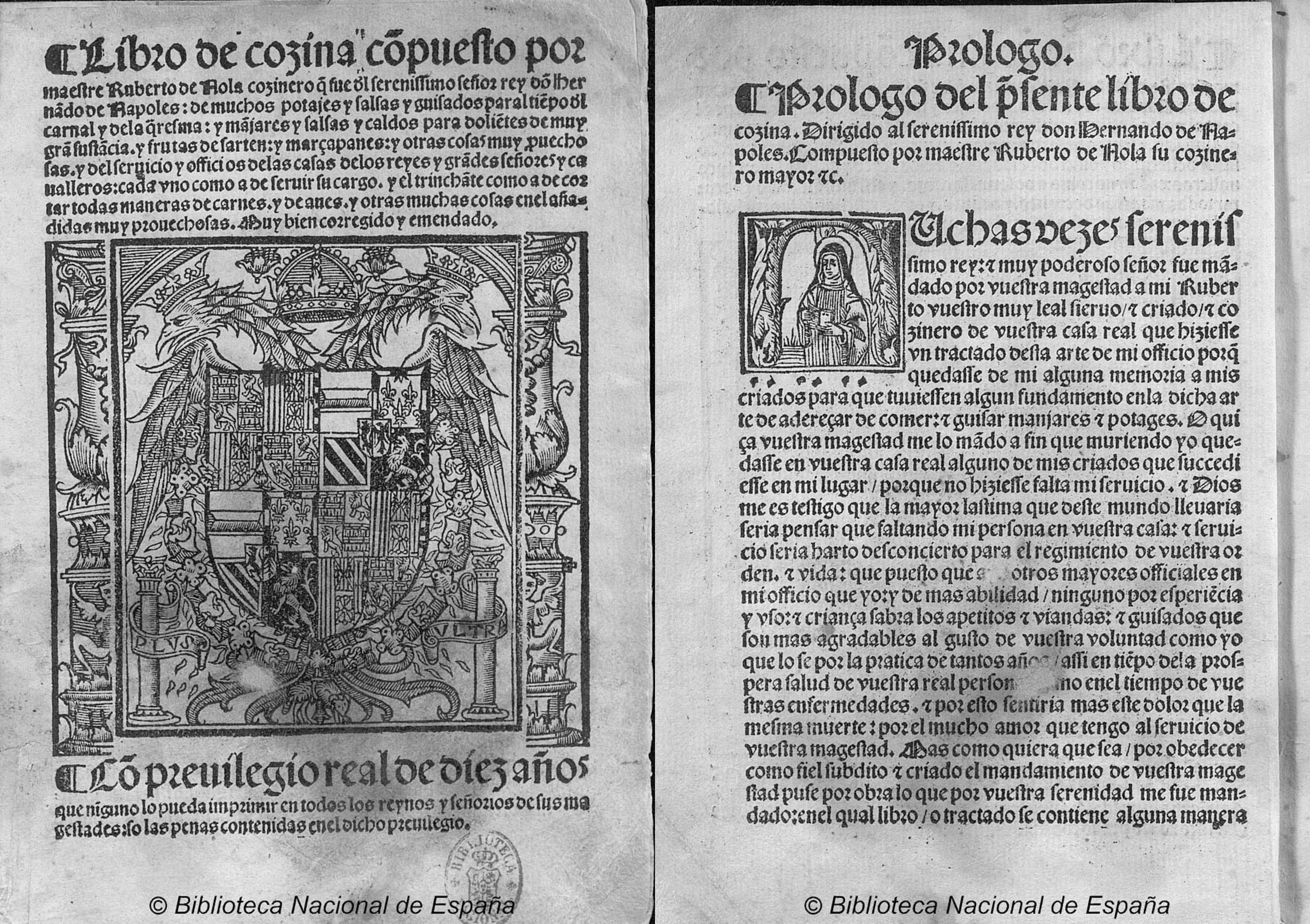

Libro de Cozina

Biblioteca Nacional de España

The National Library of Spain’s oldest cookbook is a copy of De re coquinaria from the 15th century. But we’ve included here the 16th-century Libro de cozina cōpuesto por maestre Ruberto de Nola, which is the first cookbook ever published in Castilian Spanish. According to the library, the “recipes are based on Llibre de Sent Soví, a medieval cookbook, although it adds some recipes of Occitan, French, Italian, and Arab origin.”

The book was a translation of the work of Catalan chef Ruberto de Nola, chef to King Ferrante of Naples. Both the De re coquinaria and the Libro de cozina were featured in a project where chefs cooked 12 recipes from the library’s oldest and most important cookbooks, including a recipe for Moorish-style eggplant from Ruberto de Nola’s cookbook.

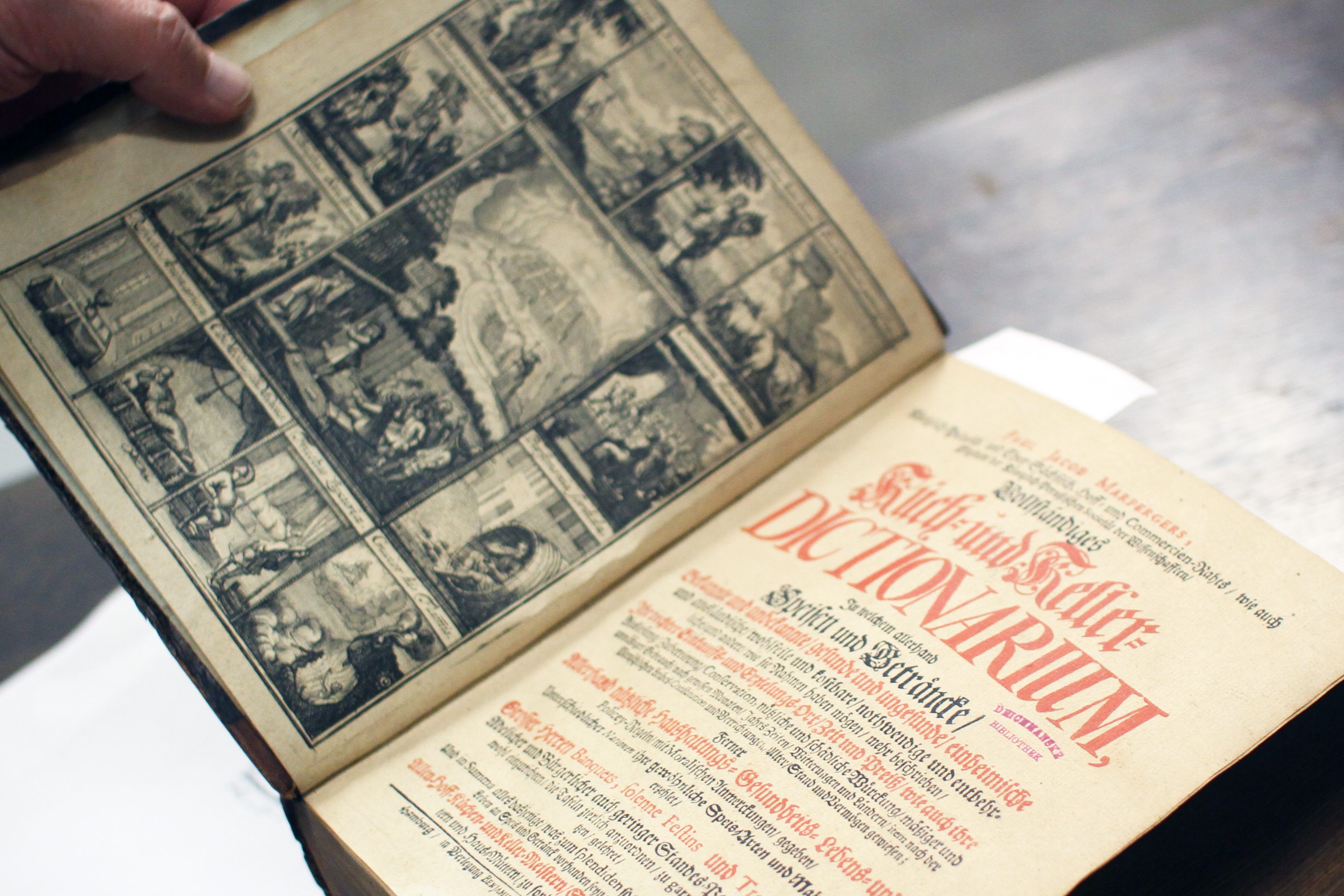

Complete Kitchen and Cellar Dictionary

The Oslo Public Library

The Oslo Public Library, known as the Deichman Library, has a 1716 copy of the Complete Kitchen and Cellar Dictionary, written by the prolific German writer Paul Jacob Marperger. Lavishly printed and more than a thousand pages long, the title page promises a book “in which all sorts of food and drinks, known and unknown, are described.” It belonged to a Norwegian lawyer named Johan Fredrik Bartholin, who donated it to the city of Christiania (the former name for Oslo) in 1784. The book has been in the Deichman collection since it opened in 1785.

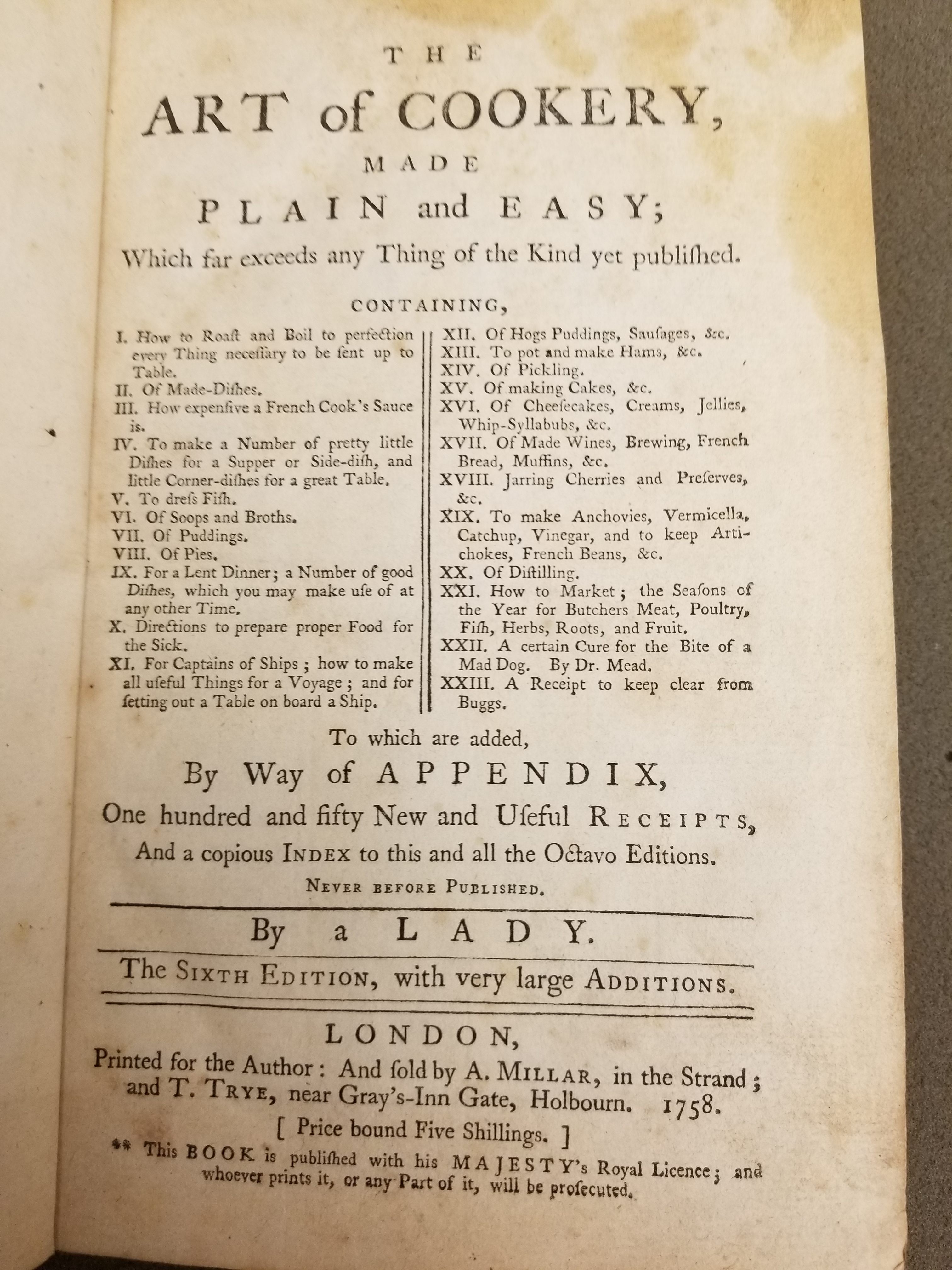

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy

The Free Library of Philadelphia

Hannah Glasse’s compendium of culinary and household recipes, including one “to make a Currey the India Way,” made it a favorite in British kitchens and in colonies abroad. Many American founding fathers had a copy, and the Free Library of Philadelphia owns a sixth edition, published in 1758.

The volume proved so successful that authorship was ascribed for centuries to a man, since, according to the famed English writer Dr. Samuel Johnson, “Women can spin very well; but they cannot make a good book of cookery.” But though Glasse borrowed many of her 972 recipes from other authors, as was the custom of the time, she undoubtedly was the compiler of the 18th century’s most popular cookbook, which Google honored with a Doodle on the anniversary of her 310th birthday.

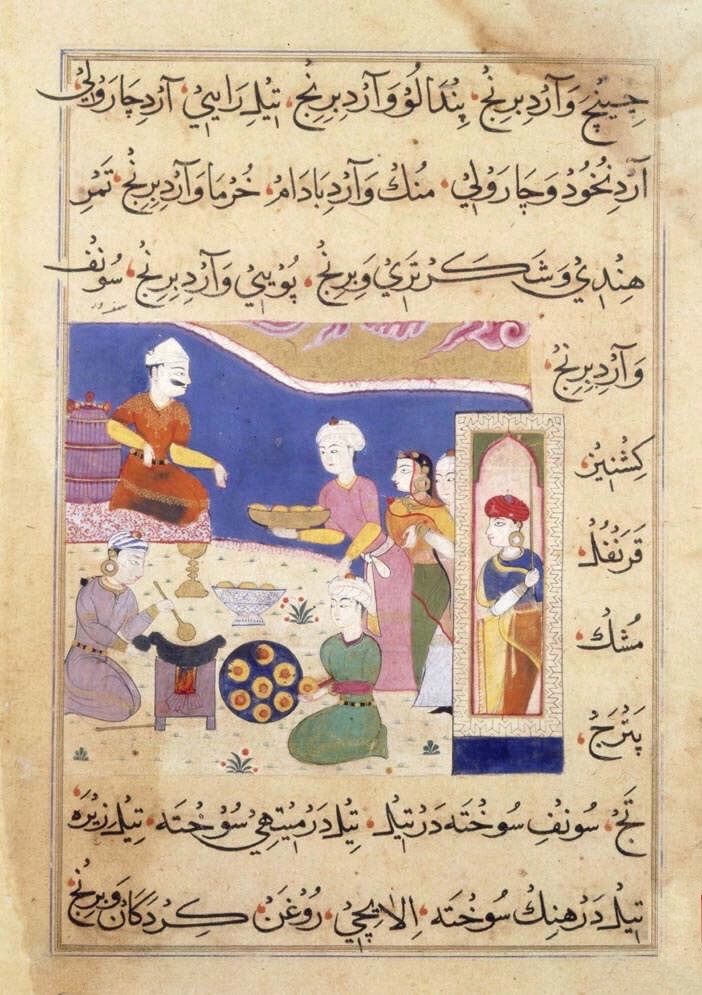

Kitāb-i Niʻmatnāmah-i Nāṣirshāhī

British Library

The British Library is home to an early cookbook from India, Nasir Shah’s Book of Delights (Kitāb-i Niʻmatnāmah-i Nāṣirshāhī), which dates to around 1500. The manuscript is in Persian, one of the main languages of poetry, scholarship, and administration in India at the time. It was commissioned on behalf of Ghiyath Shahi, an eccentric ruler of the Sultanate of Malwa in 16th-century central India. Ghiyath appears in many of the book’s color miniatures, a flamboyant figure with an oversized mustache and a taste for golden shoes.

The Book of Pleasure testifies to Ghiyath’s love of luxury (he really liked his gold, considering that there’s a recipe for rice served with gold leaf). His kitchen blended the culinary traditions of India with those of Central Asia, Persia, and beyond. Judging from the sheer number of samosa recipes, Ghiyath was a fan of the deep-fried pastry, which his cooks prepared with “finely minced deer meat” flavored with fenugreek, and spices like saffron, cloves, coriander, musk onions, and rosewater. He also relished spiced mango sherbets and took his aphrodisiacs in food form. To ensure “good sexual intercourse and improved flow of semen,” the cookbook’s author recommended frying the “brains of the domestic sparrow” as they “produce strong lust.”

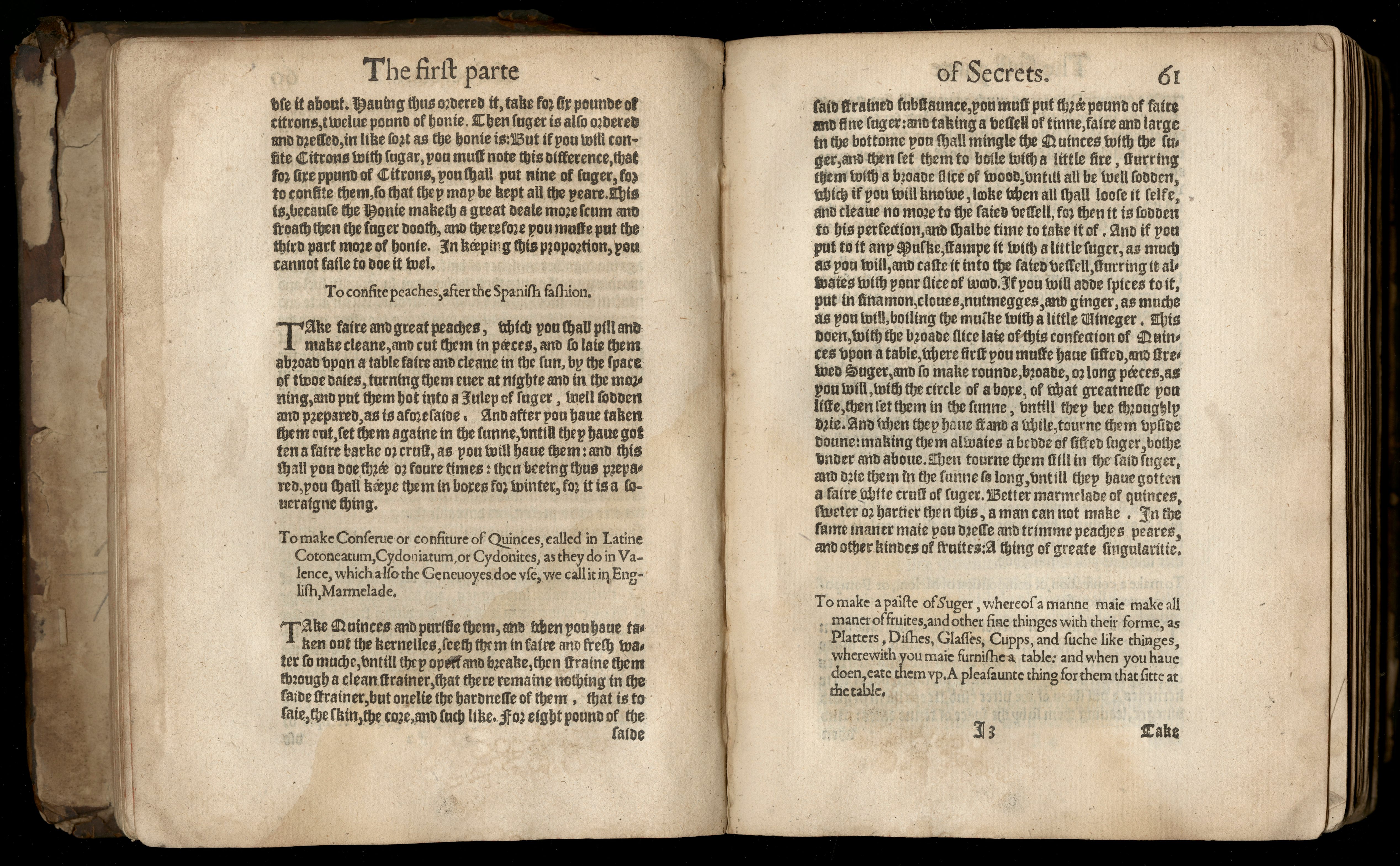

The Secrets of the Reverend Maister Alexis of Piedmont

Cardiff University

When thinking about a book full of “secrets,” a diary might come to mind. But in the Special Collections and Archives at Cardiff University, one book contains “secrets” that include an excellent marmalade recipe. The secrets of the reverend Maister Alexis of Piedmont, translated into English, was published in London in 1595.

Librarian Lisa Tallis says that, like many early cookbooks, it contains “various medicinal, domestic, and culinary recipes.” Alexis of Piedmont was thought to be the pen name of Girolamo Ruscelli, an Italian mapmaker and alchemist. His popular book started a centuries-long trend of publications filled with “secretive,” often-alchemical recipes.

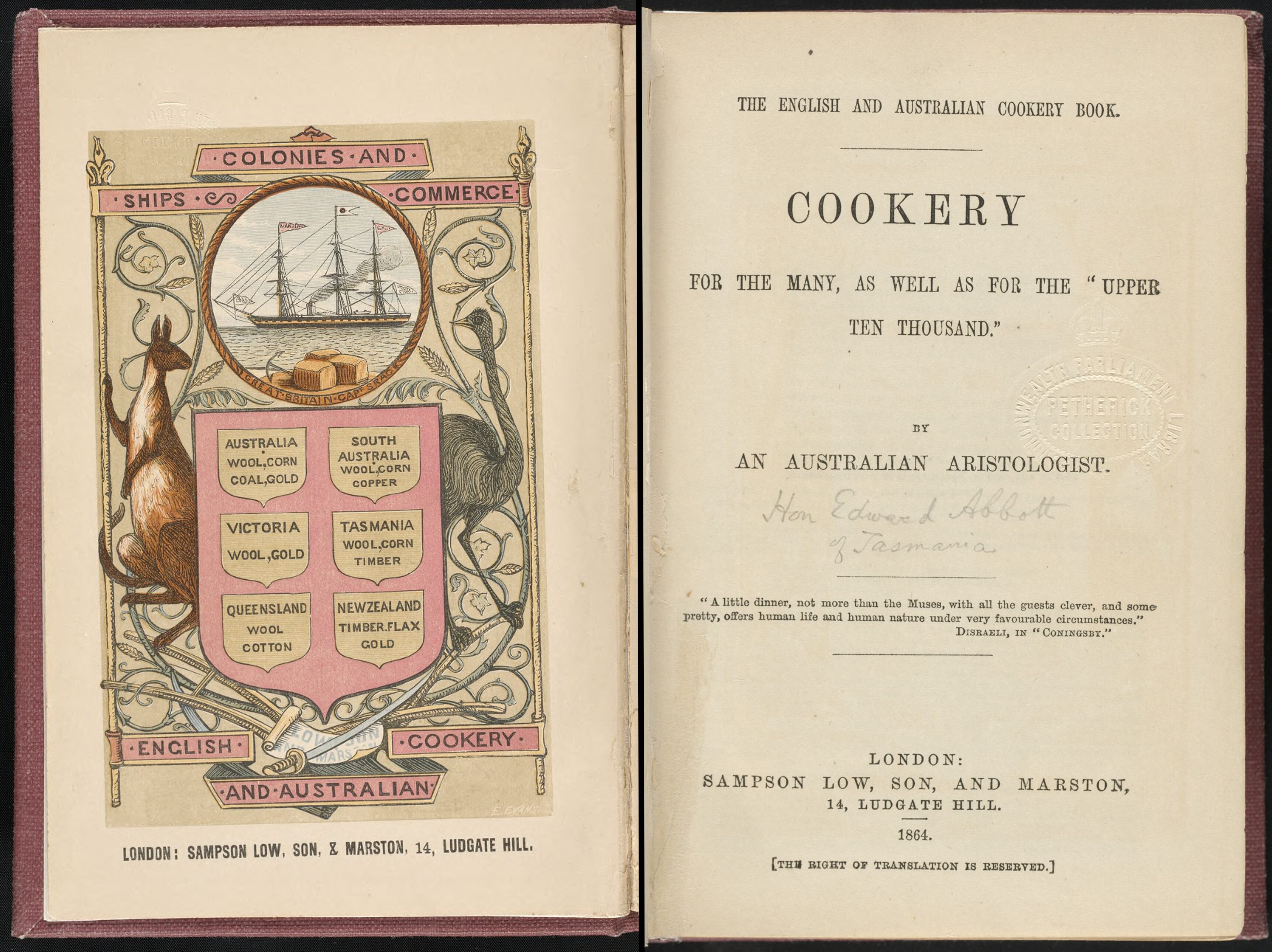

The English and Australian Cookery Book

National Library of Australia

While the National Library of Australia has a number of older English cookbooks in its collection, they also own a copy of what is considered one of Australia’s first cookbooks, The English and Australian Cookery Book (1864). The book is attributed to Edward Abbott, a Tasmanian “aristologist” who wrote the book anonymously. (An aristologist is an expert on the subject of eating and cooking.)

A publisher and parliamentarian, Abbott was nevertheless an eccentric; he once attacked the Tasmanian premier with an umbrella. The English and Australian Cookery Book was Abbot’s attempt to diversify the colonial Australian diet with local flora and fauna. Recipes include Slippery Bob, or kangaroo brains fried in emu fat, and a powerful cocktail called a “Blow My Skull,” which is made of lime, sugar, rum, porter, and brandy.

This article was updated and expanded on June 8, 2022.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook