The Rare Archival Photos Behind ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’

While investigating the heinous Osage murders for his new book, David Grann also came to know the victims’ faces.

One day in 2012, when I was visiting the Osage Nation Museum, in Oklahoma, I saw a panoramic photograph on the wall.

Taken in 1924, the picture showed members of the Osage Nation alongside white settlers, but a section had been cut out. When I asked the museum director why, she said it contained the image of a figure so frightening that she’d decided to remove it. She then pointed to the missing panel and said, “The devil was standing right there.”

My new book, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, grew out of trying to understand who that figure was, and the investigation led me to one of the most sinister crimes in American history. In the early 20th century, the members of the Osage Nation became the richest people per capita in the world, after oil was discovered under their reservation. Then they began to be mysteriously murdered off.

In 1923, after the death toll reached more than two dozen, the case was taken up by the Bureau of Investigation, then an obscure branch of the Justice Department, which was later renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation. It was among the F.B.I.’s first major homicide investigations.

During my research, I collected an extensive archive of photographs. They provide another essential means of documenting a crime largely forgotten by history. What follows is a collection of some of the most revealing photographs, as well as a clip of related film footage.

In the early 1870s, the Osage were driven from their lands in Kansas onto a rocky, presumably worthless reservation in what was then Indian Territory, and would later become part of Oklahoma. This photograph shows an Osage camp on their new reservation:

Around the turn of the century, oil deposits were discovered under this land. To extract that oil, prospectors had to pay the 2,000 or so registered members of the nation for leases and royalties. In 1923, these Osage received collectively what would be worth today more than $400 million. At the time, it was said that whereas a typical American might own a car, each Osage owned eleven of them.

The footage below—recorded by an Osage in the 1920s and shared with me by a descendant, Meg Standingbear Jennings—provides a glimpse of what the region looked like during the oil boom.

Demand for access to the vast oil deposits under the reservation was so great that there were regular auctions for leases held in Pawhuska, a city in Osage County, Oklahoma. Oilmen, such as J.P. Getty and Frank Phillips, would bid in the shade of a stately tree, which became known as the Million Dollar Elm.

As the Osage’s prosperity increased, members of the tribe began to die under mysterious circumstances. The family of one Osage in particular, Mollie Burkhart, became a prime target of the conspiracy.

In many ways, Mollie, who was born in 1886, straddled not only two centuries but two civilizations. She grew up in a lodge, speaking Osage; within a few decades, she lived in a mansion and was a married to white settler.

One night in May of 1921, Mollie’s older sister, Anna Brown, disappeared.

Anna’s body was subsequently found in this ravine on the reservation.

Within two months, Mollie’s mother died of suspected poisoning. At the Osage Nation Museum, I discovered this picture of Mollie with her mother and her sister Anna:

Mollie had a third sister named Rita Smith.

She lived with her husband Bill and a maid in this house, not far from Mollie:

Early one morning in 1923, Mollie heard a loud explosion. Someone had planted a bomb under her sister’s house that killed everyone inside, including Rita.

And it wasn’t just Mollie’s family that was being systematically eliminated. Another Osage, Henry Roan, was shot in the back of the head.

Several of those who tried to catch the killers were also killed, including a lawyer, W.W. Vaughan, who was thrown off a speeding train. He left behind a widow and ten children.

When the FBI took up the case, in 1923, agents badly bungled the probe. They released Blackie Thompson, a notorious outlaw, from prison, hoping to use him as an informant; instead, he robbed a bank and killed a police officer. Thompson would later be gunned down by lawmen, as shown in the photograph below:

J. Edgar Hoover, who was appointed director of the Bureau in 1924, feared that a potential scandal could end his dreams of building a bureaucratic empire.

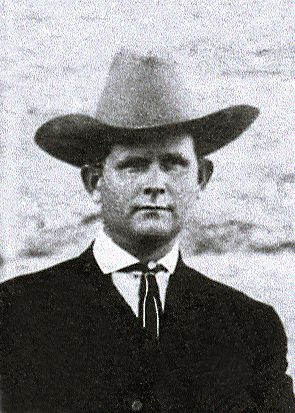

In desperation, he turned to Tom White, a former Texas Ranger, to take over the case.

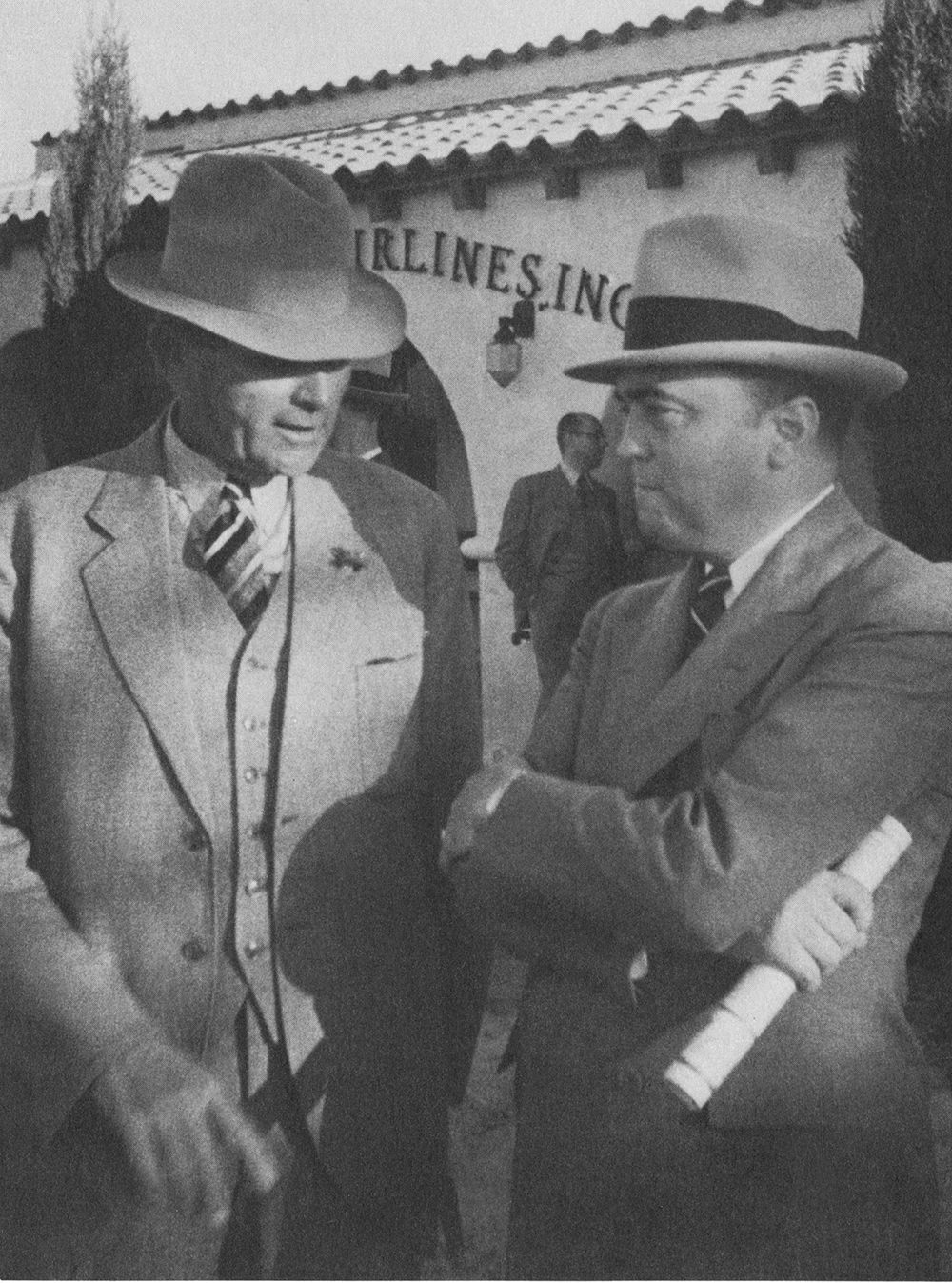

Like Mollie Burkhart, White reflected the transformation of the country. He was born in a log cabin on the frontier in Texas and began his career as a lawman when justice was often meted out by the barrel of a gun. By the time of the Osage murder case, he wore a suit and filed paperwork and had adopted the modern techniques of investigation, such as fingerprinting and handwriting analysis. Here’s a later photograph of White with Hoover:

To unravel the mystery, White assembled a team of undercover operatives, including the bureau’s only American Indian agent. Some of them posed as cattlemen, another as an insurance salesman. Eventually they were able to capture one of the masterminds of the murderous plot. But, as I discovered from my research, the extent of the killings was far greater than the Bureau ever exposed, and there were scores, perhaps hundreds, of murders that went unsolved.

Much of the Osage’s oil money was swindled, and over time the oil deposits on their land have also diminished. Many of the old boomtowns of this era now resemble ghost towns. This photograph shows a boarded-up bar in a town where Mollie’s sister, Anna Brown, was seen before vanishing:

This is what the prairie looks like today:

I interviewed many of the descendants of the victims, including Margie Burkhart, who is a granddaughter of Mollie Burkhart.

She took me to a cemetery in Grayhorse, in Osage County, where many of her relatives who were murdered are buried.

When I visited the Osage Nation Museum, the director had retrieved, from the basement, an image of the missing panel. It showed the killer whom the FBI had arrested—he was the so-called devil. The Osage had removed the panel not to forget what happened, as so many Americans had, but because they can’t forget.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook