The Ghost Subway Station in Paris Where Films Come to Life

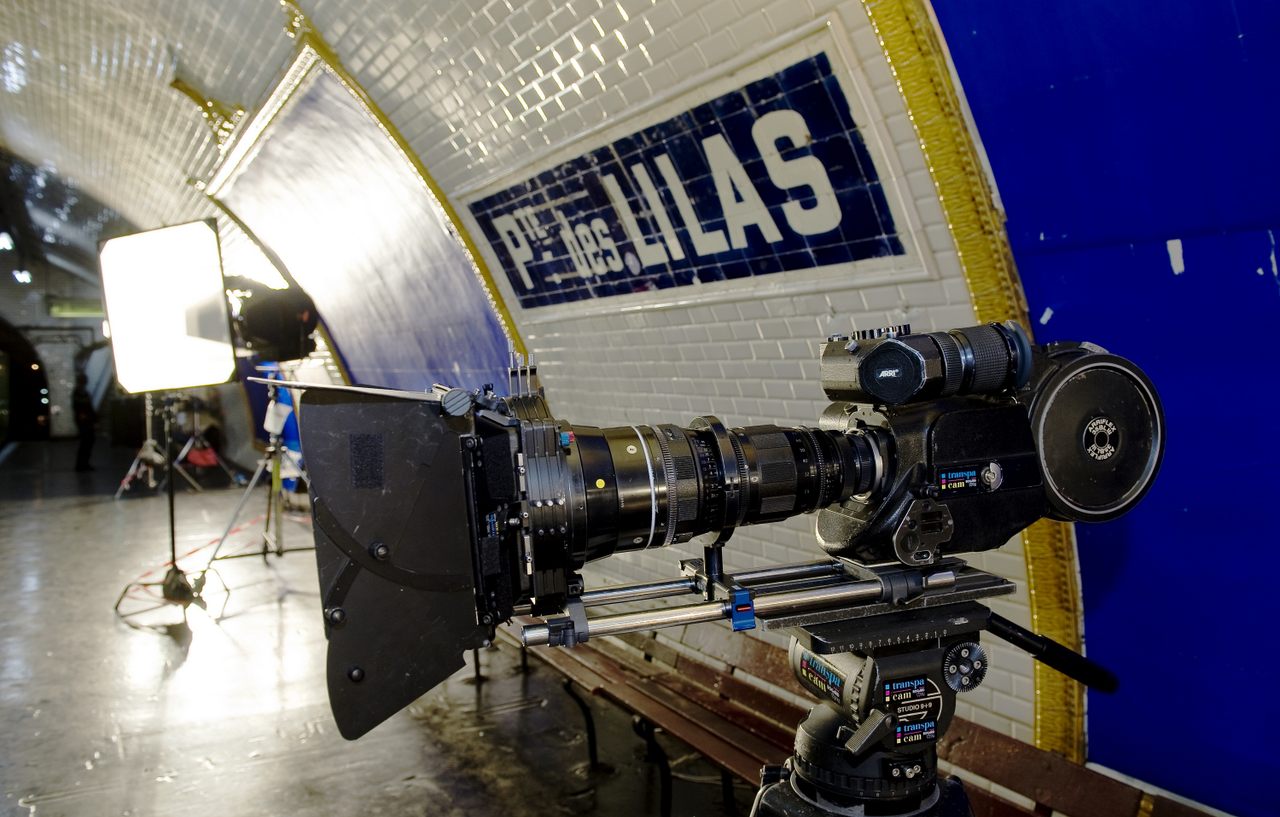

In Porte des Lilas, it’s lights, camera, Métro!

Meryl Streep as Julia Child, on her way to meet a famous cookbook writer in Julie & Julia. Audrey Tautou as Amélie Poulain, running into her future lover in Amélie (Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain). Steve Buscemi as a clueless American tourist in Paris, je t’aime.

Shot far from the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, and the glamour of the French capital, these scenes capture the gritty realism of Parisian life, albeit with a touch of movie magic. They were each filmed in a decommissioned subway station that’s been dedicated to film, television, and commercial productions for the past several decades. Yet Porte des Lilas remains something of an industry secret—even in the country where cinema was invented, and despite the fact that several films a year are shot there.

In use until 1929, this part of the station—a decommissioned area hidden behind a door in the otherwise functioning Porte des Lilas Métro stop, on the eastern edge of the city (one of a handful of ghost stations, or partial ghost stations, in the Paris underground)—has been used as a film backdrop since the 1970s. For directors who want to shoot there today, €20,000 buys a “complete shoot” with a train and staff, plus the freedom to transform the station, and the trains stationed there, however they wish. All told, the “studio” accommodates up to 150 people, with two platforms and up to five trains that can move about a kilometer or half a mile through a loop of tunnel that’s disconnected from the rest of the Métro system.

The benefits of filming in Porte des Lilas are numerous. For one thing, directors have total control of the environment, while maintaining the illusion of filming in a public space. For another, they have the safety measures put in place by the Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens (RATP), the state-owned public transport operator. This is crucial when a filmmaker is shooting moving vehicles surrounded by high-voltage rails.

To stage a sequence in which firefighters respond to a suicide jumper in the Métro, French director Frédéric Tellier was able to film directly on the tracks in the 2018 film Sauver ou périr (released in English as Through the Fire).

Another French director, Jean-Paul Salomé, configured a similarly complicated Métro setup for his 2008 work, Les femmes de l’ombre (released in English as Female Agents), a World War II period piece. The plot involves five female resistance fighters who plot to murder an SS colonel in the subway, until—spoiler alert!—their plan goes awry. Salomé originally planned to shoot this climactic scene on Boulevard Saint-Germain, near the famous Café de Flore. But blocking off a busy part of the city was too complicated. Besides, he enjoyed the claustrophobic aspect of the Métro, which he says reinforces the idea that the five women, and the Nazis, had found themselves in a trap.

But there was a catch: The site didn’t have enough 1940s-era Métro cars. Salomé described filming the scene as a sort of “mathematical problem” that had to be solved (with special effects) in order to create the illusion that there were actually two full trains. “There were gunshots,” he says. “There were windows exploding. There were dead people. There was blood. It wasn’t easy to do.”

For his part, Tellier says he was drawn to the site’s particular aesthetic quality. “I find it quite striking,” he says. “This whole underground, this tunnel which a train with cars and people in it goes through, this distinctive yellow lighting inside the cars, the white tiles all around, the blue station name. There is something quite photographic [about it].”

Tellier says he chose the subway over, say, a bus in order to further the plot of his film. In it, the protagonist, Franck Pasquier (played by Pierre Niney)—a Parisian firefighter who becomes disfigured in a blaze—has to come to terms with how he looks; the underground setting provides a sort of veil of secrecy for the character’s spiritual and physical journey.

For the Métro scene, set decorators created a fake advertisement for a perfume featuring a male model. Tellier says he wanted to capture “the exchange of looks” between Pasquier and the man in the ad, and to show the transportational reality of someone who wouldn’t have a chauffeur to drive him places.

(Ironically, the high cost of renting the station limits the types of productions that can be shot there. Porte des Lilas is largely used for big-budget movies and commercial projects with significant financial backing.)

Behind each of these works is Karine Lehongre-Richard, the manager in charge of all shoots on public transportation in the Paris region. Dubbed “Madame Cinéma” by Le Parisien, Lehongre-Richard organizes around 60 projects a year. She handles all the administrative and logistical aspects, including reading scripts and studying a proposal’s technical feasibility. This involves coordinating not just film crews, she writes in an email, but also RATP agents, drivers, and maintenance operations. The goal, she says, is to show how Parisians’ lives are linked to public transportation.

“It is as much a part of their daily lives as it is of the landscape,” she writes, “just like the great monuments and mythical neighborhoods.”

Many people outside the film industry don’t know about the station’s existence. But since 2012 it has been open to the public once a year, for European Heritage Day—a date when anyone can access some of the continent’s most interesting (and often restricted) sites, including the Palais-Royal and the archaeological crypt beneath Notre-Dame.

The pandemic halted filming last spring, but production in Porte des Lilas has been picking up again lately. Lehongre-Richard says that’s essential to furthering the heritage of the Paris Métro, a 120-year-old institution. The film Les Femmes de l’ombre, for instance, featured one of the resident trains, the Sprague-Thomson car, which is classified as a historical monument. Its carriage was the first in the Paris Métro made entirely of metal instead of wood—a change prompted by a fire in 1903 that resulted in 84 deaths. The Sprague-Thomson is also featured in Julie & Julia, as director “Nora Ephron found our historical train beautiful,” writes Lehongre-Richard.

But of all the films shot in Porte des Lilas, she says, one international hit has done the most to promote Paris’s public transportation. “The film Amélie … is a postcard of Paris, but also of the Parisian Métro.” The film’s popularity—the café where Amélie worked, in the Montmartre area, is now a tourist destination—has done much to shape foreign perception of the French capital over the past two decades.

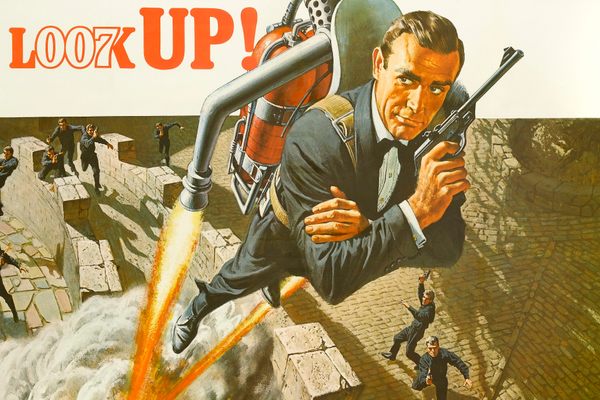

Of course, it’s hardly alone: From Funny Face (1957) to Midnight in Paris (2011) to Emily in Paris (2020), movies and television shows have capitalized on the City of Lights’s enchantments and romantic allure.

(It’s worth noting, however, that many of these depictions take a narrow view of Paris, relying on stereotypes and frequently ignoring diversity. In Emily in Paris, for instance, the titular character glides through a city seemingly free of trash, and makes few excursions to the outer arrondissements. Unsurprisingly, Emily never takes the Métro.)

Oscar-nominated art director and production designer Patrice Vermette worked in Porte des Lilas on Jean-Marc Vallée’s 2011 film, Café de Flore. Vermette says Vallée is a music-oriented director who was inspired to film in the station by Serge Gainsbourg’s song “Le poinçonneur des Lilas” (“The Lilas Ticket Inspector”). In fact, the title of the movie refers not to the popular Parisian café but to the song of the same name by British electronic musician Matthew Herbert.

Café de Flore focuses on two seemingly unrelated stories—one set in 1960s Paris, the other in modern-day Montreal. Vermette remembers picking two Métro cars to fit the time period in France, but having to change the upholstery and work to cover up any anachronisms. In post-production, the filmmakers even “dirtied up” some of the buildings, because the Paris of that era was much grimier than it is now due to pollution. Vermette says that scenes shot in the Métro today can still offer new views of a city that has captivated filmmakers since the dawn of cinema.

“I think [the subway is a great place] to show the vibe of a city, especially like Paris,” says Vermette. “It’s just living the life as Parisians, portraying the city as if it’s natural. It’s not forced. It flows because it’s Paris.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook