Life Under Lockdown, as Seen Through 16 Disposable Cameras

A collaborative photo project tells personal stories of the pandemic in the U.K.

As the COVID-19 pandemic rushed across the United Kingdom in mid-March, the London-based photographer Emma Mowat wondered how daily life was going to look in the weeks ahead. She wanted to see the public health crisis through other people’s eyes—so she sent 16 disposable cameras to people across the United Kingdom. By leveraging her personal network and Instagram followers, she found collaborators in such places as Newcastle, Edinburgh, Manchester, Sussex, and Stafford.

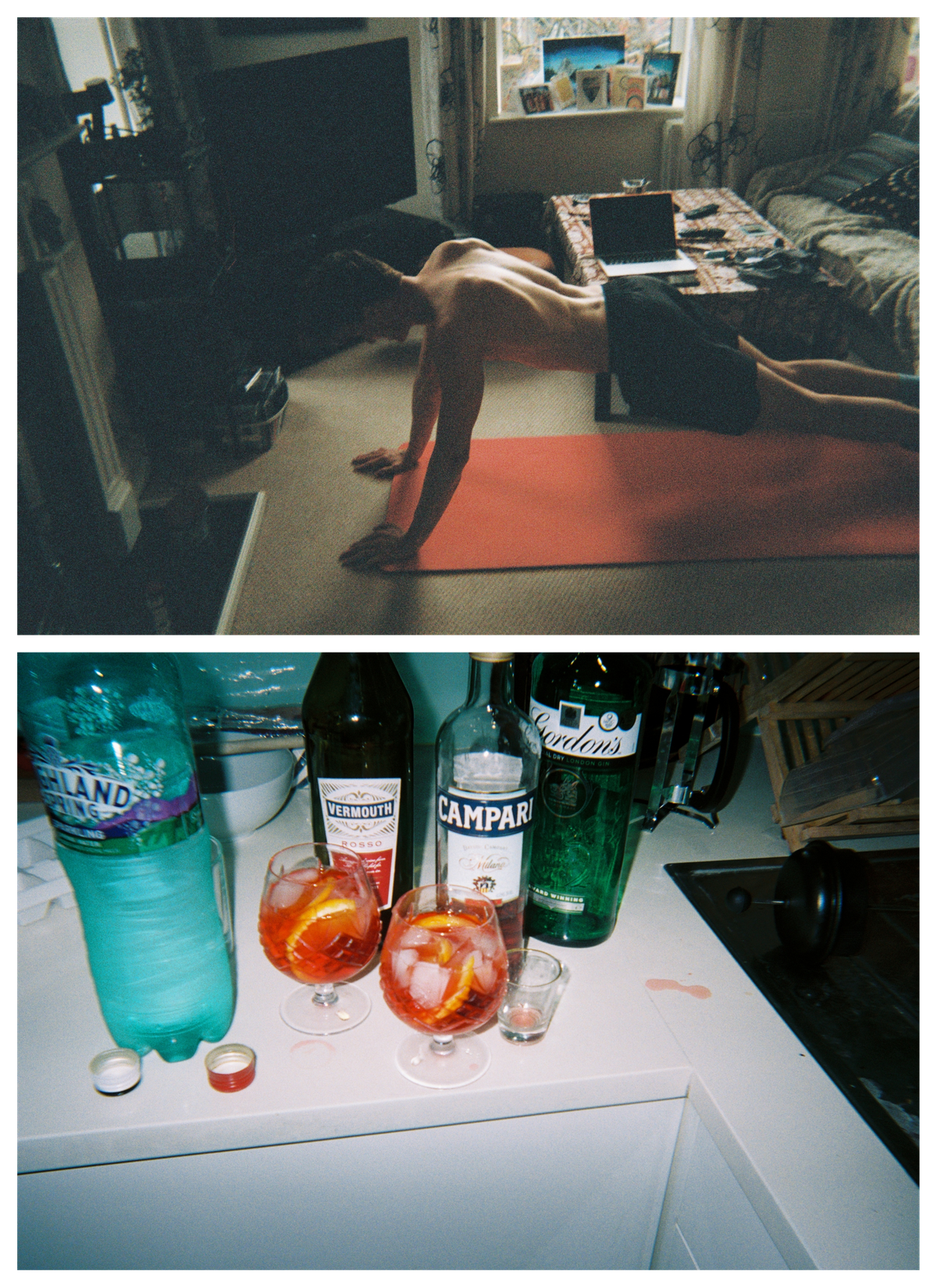

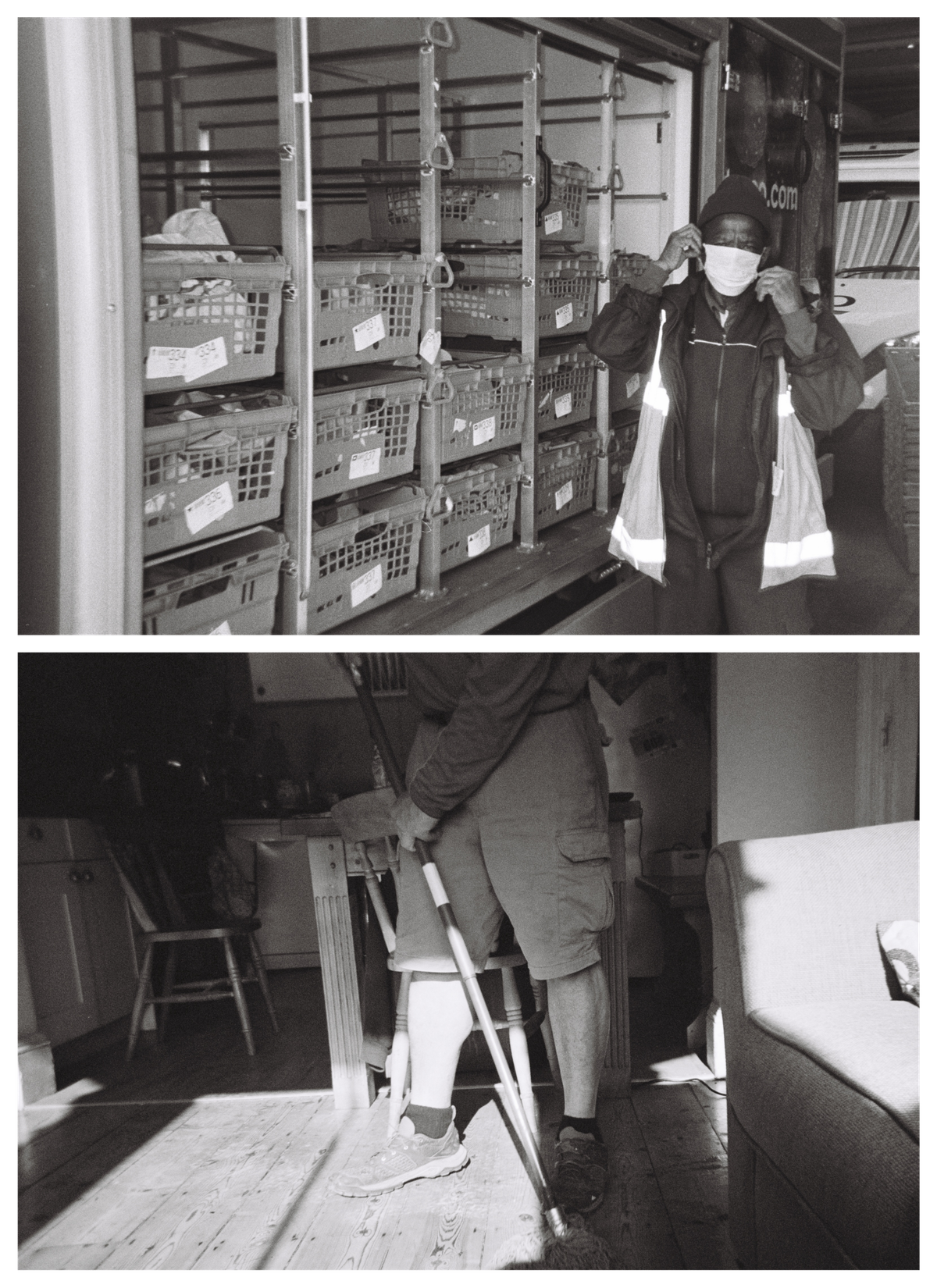

Some of the cameras shot in black and white, others in color; all had 27 exposures, which the recipients could use to chronicle their topsy-turvy new lives. The photographers varied in age and profession, from a Tesco driver who made home deliveries while wearing a mask to a general practice doctor in Manchester, who had to brush up on working with a ventilator.

After a month or so, everyone returned their cameras to Mowat, who sent off the film to be developed. She chose an image from each camera and stitched the selections together into a photo essay, “Notes From a Nervous Nation.” The subjects range from a batch of boozy drinks to a white, rumpled comforter to trees heavy with pink blooms. In April, Mowat photographed a well-coiffed woman in a mask and plastic gloves, leafing through a newspaper on a park bench. (The woman later messaged Mowat to say that she had been escorted out for sitting and lingering a little too long.)

As life presses on amidst the pandemic, Mowat hopes the series will offer a bit of comfort. “We are going through this together,” she says. “Wherever we are.” Atlas Obscura talked to her about art, crisis, and collaboration.

What inspired this project? When did you first think of it?

As we slipped into lockdown, I had a strong feeling that, although we didn’t quite know what was coming, what it would consist of, or how it would feel, things were changing. It felt instinctual to start a project that captured this time as the virus started gaining ground. I realized that the photos could provide a time capsule for the future.

What appealed to you about a crowdsourced project, and why disposable cameras?

Storytelling at a human level is always important when crisis strikes. It helps us to make sense of complex situations. For me, participatory art was important to capture how the pandemic is affecting people differently, as we all reorient our relationship with ourselves and the outside world. I was able to get an intimate insight into people’s lives by placing cameras into the hands of those who would not typically turn to photography.

It was also appealing to tap into a slower form of photo making, compared to photographs taken with phones. I wanted to encourage a more meditative approach, in which the participants were not able to edit the photos they had taken.

What instructions, if any, did you give about what to shoot, and when?

For those hunkering down at home, I suggested they focus on capturing the benign, the beautiful, and the boring moments of their lockdown experience. I wanted people to look differently at the world they are familiar with—to find a way to spark interest and creativity in their homes. I encouraged the key workers, where possible, to take their cameras with them to work to capture the unraveling of their daily experiences.

I also wanted to collect written memories and experiences of people who were participating, so I asked them to share items such as the music they were listening to, new habits, to-do lists, journal entries, and poems.

Did anything surprise you about the photos people took?

Many non-essential workers involved in the project reflected on the moments of stillness that descended upon their days, despite the dizzying headlines and fear for loved ones. A lot of people have relaxed into the rhythm of the monotony, grateful for the gift of time as spring has appeared with its blossom and chorus of birds, their tune no longer deafened as the roads and skies are clear of their usual traffic.

There is no doubt that many people are struggling with their mental health, stuck indoors and forced to find comfort in the absence rather than the presence of others. However, I would not have predicted how some people have appreciated the lull that has enveloped their lives.

What criteria did you use to choose the photos from each camera?

When you’re doing a photo essay, you’re trying to suggest a narrative. To decide which photographs to include, I was first guided by my intuition. It could be as simple as the colors within the shot, or that it felt unusual in some way. I also wanted to weave together a combination of portraits, places, and things, thinking about how the photos work together in a meaningful way. It was all about uncovering the human experience. That’s why I would say that perhaps the Tesco delivery guy with his mask has the power to tell the story of the pandemic in one shot.

Is there some aspect of life in the time of COVID-19 that you haven’t shot yet, but would like to?

It will be interesting to capture the world we will wake up to as we put ourselves back together again, not only personally but societally. For now, this project is complete. It could be interesting, however, to do a second wave as we emerge from lockdown. As we reconsider who we are and what we value, I would love to photograph the human stories that emerge from our new reality.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook