One of the Earliest Industrial Spies Was a French Missionary Stationed in China

When he wasn’t converting people, Father Francois Xavier d’Entrecolles was extracting trade secrets from porcelain producers.

Plenty of today’s technological arms races involve an element of industrial espionage. An executive from Uber has been accused of stealing autonomous car-related data from his old employer, Google. Just this month, the same company was accused of using hidden tracking software to keep tabs on their chief ride-hailing rival, Lyft. And China is trying to partner with the European Union on a suite of new moon bases partly because they can’t work on scientific projects with the United States, thanks to laws meant to prevent secret-stealing.

But intellectual property theft hasn’t always involved elaborate software programs and moonshots. Back in the 17th century, all it took to steal trade secrets was a Jesuit missionary with an eye for detail who was fluent in Chinese and willing to spend a lot of time in a ceramics factory.

When Francois Xavier d’Entrecolles joined the priesthood in 1682, he probably didn’t plan to become the world’s first industrial spy. As the historian Robert Finlay writes in The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History, d’Entrecolles was a skilled translator with “a passion for the curious and unusual, along with a gift for sifting and marshaling information.” Known for his friendliness and wisdom, he was sent to China in 1698, along with nine other missionaries.

As Finlay explains, Jesuits at the time saw their missionary work as a kind of back-and-forth—as they spread the teachings of Christianity and Western science to other countries, they gathered valuable local knowledge in return. Priests came back from their missions with everything from technological plans to bags of malaria-curing cinchona bark. Carl Linnaeus developed his system of classification with the help of Chinese plant samples that were sent to him by a Jesuit missionary.

Although many of these were lucky discoveries, d’Entrecolles’s experience was slightly different. When he set out from France, he did so with a particular assignment. At the time, much of Europe was seized with a mania for imported porcelain— in the words of the English journalist and author Daniel Defoe, everyone who could afford to was “piling china up on the tops of cabinets, escritoires and every chimney-piece, to the tops of the ceilings… till it became a grievance.”

Virtually all of this valuable material came from the Chinese city of Jingdezhen, where it had first been invented, and which roared all day and night with fires from the kilns. Although Europeans guessed at how the people of Jingdezhen made this “white gold,” they were pretty far off. (One account diagnosed it as an eggshell-and-fish-scale mixture that was shaped into plates and vases, and then left underground for a century to cure.) Attempts to reverse-engineer the process had likewise been unsuccessful. The ruling class was growing impatient—increasingly, “there was intense interest at the French court… in discovering how porcelain was made,” Finlay writes. “D’Entrecolles’s superiors plainly sent him to Jingdezhen on a mission of industrial espionage.”

It was a difficult job. D’Entrecolles had to deal with scrutiny on a number of levels. Many trade secrets were kept within families, passed down to the next generation only when the previous one retired. When he was allowed to visit the factories, d’Entrecolles, despite his fluency in Chinese, struggled with the workers’ job-specific lingo. Although the would-be spy made it to Jingdezhen around 1700, over a decade had passed before he was able to mail a description of his findings to France.

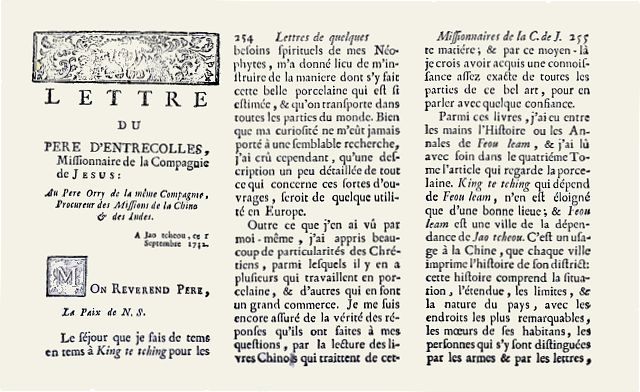

This first letter, sent to the treasurer of the Jesuit missions to China in September of 1712, makes the author’s intentions clear immediately. “My Reverend Father,” it begins, “The visits that I have made from time to time at Jingdezhen… have given me in turn an opportunity to instruct myself concerning the manner in which one makes this beautiful porcelain which is so admired and which is exported to all parts of the world… I believe that a detailed description of all that is concerned with this sort of work should be of some use in Europe.”

He goes on to explain that despite the hardships involved, many of the city’s Christian converts work in the porcelain trade, and that he has checked what they’ve told him against some textbooks and “acquired a fairly exact knowledge of all aspects of this fine art.” D’Entrecolles periodically loses the plot—he gets distracted giving statistics about the city, explaining its policing strategies, and relating a local legend about a woman who gives birth to a serpent.

But by the end of the letter, he has taught his interlocutor exactly what porcelain is made of, how those materials are mixed, separated, and purified, and how the resulting clay is rolled, kneaded, moulded, and fired. He has gone over special cases (extra-large pieces; glaze preparation; crackling) and speculated about how to reconstruct various techniques that the Chinese artisans considered “lost secrets,” including kia-tsim—a glazing technique in which illustrations appear on a bowl only when it’s full of water.

A modern reader comes away with a good understanding of the porcelain-making process, as well as an appreciation for the creativity on display. D’Entrecolles tells of porcelain ducks and turtles that float on water, and realistic porcelain cats with eyes that glow when candles are put inside. (Those were meant to scare rats.)

He describes a faux-aging process, meant to make new porcelain look antique, that involves covering it with meat soup and then leaving it in a sewer for a month. He also details the complex worker assembly lines that allowed for speedy production. “It is said that one piece of fired porcelain passes through the hands of seventy workers,” d’Entrecolles writes. “I have no trouble in believing this.”

This was not quite enough for d’Entrecolles’s superiors in France. “They informed [him] that his information had not been sufficient,” writes Finlay. D’Entrecolles’s second letter, sent ten years after the first, contains even more instructions—on how to restore gilt finishes, mix a mirrored black glaze, and fortify edges so they won’t chip. (He also sent samples.) Taken together, Finlay writes, the two letters “represent one of the earliest and most calculated cases of an effort to implement mercantilist economic strategies of technology transfer.”

In the end, France was not the first country to produce porcelain in Europe—that honor went either to Germany or England (the two countries are still litigating). But at least one future porcelain maven got a lot out of d’Entrecolles’s work. The British potter and entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood was fascinated by d’Entrecolles’s letters, and copied the passage about Jingdezhen’s assembly lines into his commonplace book. Years later, he would recreate that setup in his pottery factory, assigning different workers to model, mold, paint, and fire the clay—an innovation in the field. “The triumphs of the industrial revolution thus owed something to the potters of Jingdezhen,” writes Finlay.

Similarly, any successful modern incarnation of industrial espionage—which is to say, those cases we haven’t been hearing about—may owe something to the work of d’Entrecolles, who accidentally invented an entirely new type of corporate competition.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook