Preserving Ukraine’s Soviet Past, One Mosaic At a Time

“We’re trying to collect everything before it’s gone.”

On a sunny spring day in Kyiv, Ukraine, two people stand before a massive mosaic on the side of the Institute for Nuclear Research, stepping back a few feet to take it all in. It’s rare for people to stop and take notice; most locals walk right past this artwork—wearing coronavirus masks, of course—oblivious to its dizzying array of textures, materials, and colors. Images of two working men span the width of the building, each several stories high, their bodies a rich spectrum of browns and grays. Their gaze is on the red-hot core of a star in the center of the building—a rainbow of orange and yellow rays emanating to the edges of the panel, titled “Blacksmiths of the Present.”

Across Ukraine, there are hundreds of works of art like this one. Big, bold, and bright, they convey variations of the communist propaganda that was spread across the country during Soviet times. For better or worse, they also tell the story of Ukraine’s history.

To Lubava Illyenko, it’s a story worth saving.

Born in Komsomolsk-na-Amure, Russia, Illyenko moved to Ukraine when she was 14 years old. Today she’s an art historian writing her doctoral thesis at the University of Augsburg in Germany, with a focus on Ukraine’s Soviet mosaics.

She’s also involved with a project to catalog these mosaics that’s supported by Izolyatsia (“isolation” in Russian)—a nonprofit organization that aims to create systemic changes in Ukraine via cultural initiatives. Originally located in a former insulation-materials factory in Donetsk, Ukraine, Izolyatsia was founded in 2010 by a businesswoman named Lyubov Mikhailova. It was forced to move to Kyiv in June 2014, when the territory was seized by armed representatives of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic.

Today, Illyenko—along with Izolyatsia’s curators and a team of volunteers—is pushing forward a key project to protect, preserve, and draw attention to Ukraine’s Soviet-era mosaics. “We’re trying to collect everything before it’s gone,” Illyenko says. “We’re trying to collect information about [these mosaics], the artists who created them, when they were made, and so on. Any related information, we are trying to find out.”

Many of these mosaics are falling into disrepair or, because they represent cultural and political ideals from the communism of yesteryear, being destroyed by Ukrainians eager to move beyond their Soviet past.

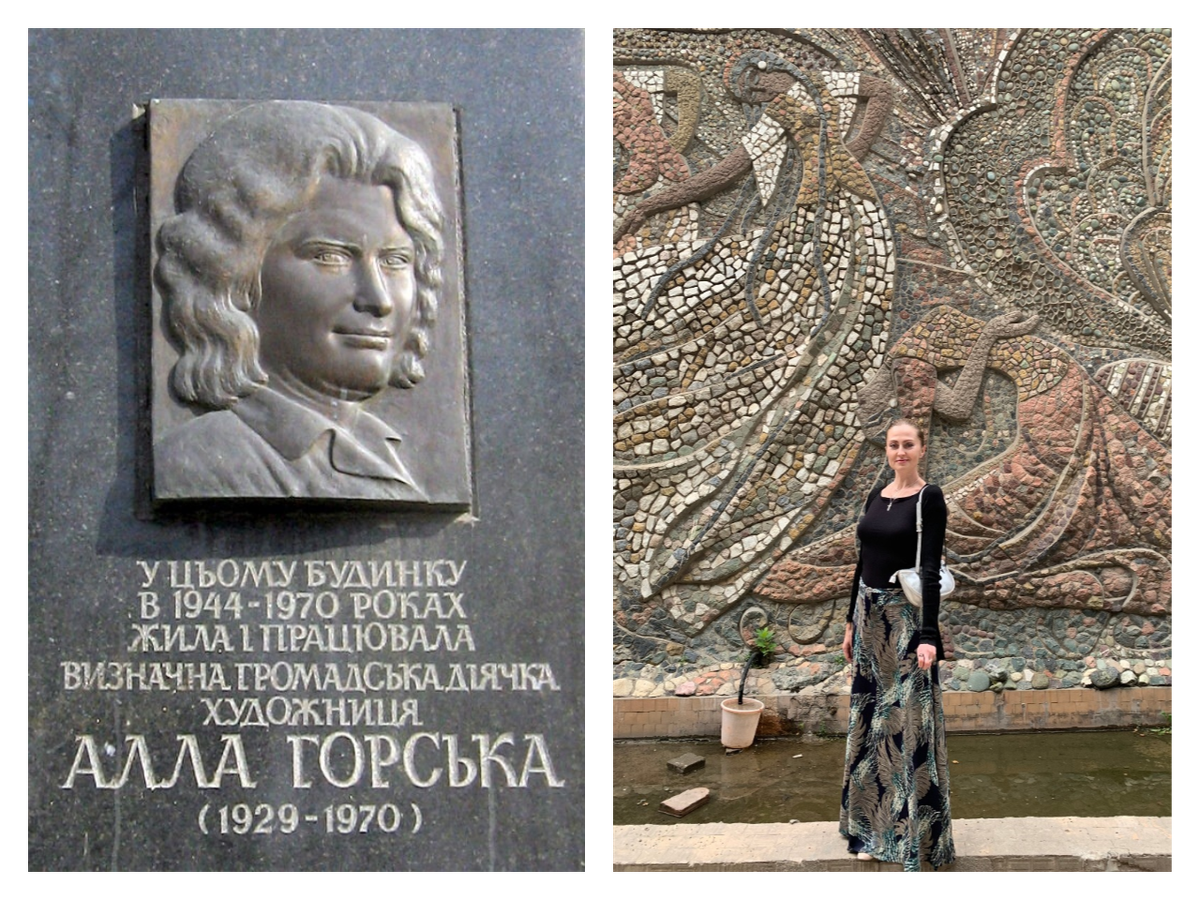

Izolyatsia is agnostic when it comes to artistic messaging. For Illyenko and others in the organization, the goal is to protect, preserve, and document all the mosaics that artists created during Soviet times. Those include several by Alla Horska, who produced controversial anti-communist works in the 1960s. Deeply involved with the Ukrainian national democratic movement of the time, she was hired as an artist by the Soviet Union to uphold Soviet ideals. Yet she simultaneously—and paradoxically—created artworks that defied them. In some ways, says Illyenko, Horska’s egalitarian spirit is what animated Izolyatsia in the first place.

Illyenko says the first phase of the project has entailed locating and identifying the surviving mosaics.

“We started taking photos of them, we started searching for information, and we were the first people trying to persuade local people to tell us about mosaics they knew about,” Illyenko says, noting that this work has inspired similar, smaller-scale preservations on a local level.

As an art form, mosaics typically consist of small glass or ceramic pieces. But in Ukraine, the umbrella term “Soviet mosaics” is more accurately defined as “art decorating architecture.” Many of these pieces, like “Blacksmiths of the Present,” are the height and width of the buildings on which they’re constructed. Some are made from ceramic tiles and glass, but others are sculpted from metal, clay, and various different materials. Most importantly, they are always found on or in buildings—and their surrounding environments are just as important to their stories as the art itself.

“When we talk about preservation, the mosaics were created exactly for these places, for these buildings. It was an architectural decision,” Illyenko says. “It’s very important that it should be preserved there, in the place it was created, because it is a synthesis of other mediums—of architecture, of space, of meaning of the space, and so on.”

Found across Ukraine, Russia, and other former Soviet republics, these mosaics—whose creation peaked during an economic boom that lasted from the 1960s to the 1980s—are heavily concentrated in cities that were industrial hubs after World War II. Their messages center on the communist propaganda narratives of community, labor, patriotism, friendship, and teamwork.

Many were damaged or destroyed in the 1990s, after the Soviet Union splintered and a wave of decommunization efforts swept through Ukraine. A second wave came during Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and the 2014 Maidan Revolution—and especially in April 2015, when the Ukrainian government approved laws forbidding communist symbols such as state flags, coats of arms, and the iconic sickle and hammer. At the time, many mosaics were destroyed or covered over by sheets of metal.

“For me, because I wasn’t born in Ukraine, it was … strange to see how all Ukrainians were demolishing the statues of Lenin—hundreds of them,” says Illyenko. “For me, every piece of art should be preserved.” She says that her status as an outsider in Ukraine is perhaps what allows her to see the inherent merit—the artistic, historic, and cultural value—in these politically fraught pieces.

The oldest mosaics Izolyatsia has cataloged are from the 1930s—portraits of Lenin and Stalin, located on a brick water tower in the city of Novhorod-Siverskyi, Ukraine. Beyond their historical value, Illyenko says, there’s another reason to preserve them: They encourage present-day discourse.

“Blacksmiths of the Present” is one such piece. Many people would likely recognize this mosaic—created in 1974 and located on the street-facing side of the Institute of Nuclear Research of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine—from the recent HBO miniseries Chernobyl. The 1986 nuclear disaster in northern Ukraine was a deadly nadir in Soviet history, in part due to the U.S.S.R.’s shameful attempts to cover up the tragedy. Today, conversations about government transparency remain a hot topic among Ukrainians (and throughout the world).

Illyenko says the piece is also aesthetically significant because it merges Soviet-specific imagery and messaging with local Ukrainian characteristics, such as vivid colors. “I really like it because it combines [communist messages] and decorative characteristics of the period on one hand and modernis[t] traditions in composition on the other hand,” she says. “I think this mosaic is very Ukrainian—its colors, its figures, its composition.”

For Izolyatsia, preservation challenges abound: natural deterioration of the mosaics due to age and the elements, private owners who don’t care about the artworks on their buildings, and construction workers who place panels over the works when they add insulation to Soviet-era structures. Furthermore, because Soviet mosaics are integrated into their architectural surroundings, they can’t just be removed and preserved like other forms of long-lost art. And very few of these pieces are protected by the national government; that usually happens only if an entire building is protected.

But Izolyatsia is doing what it can. Its signature project is an online, open-source archive aimed at cataloging all the Soviet mosaics in Ukraine. Its website includes a map of known mosaics and biographical information about the artists. Inviting Ukrainians to participate—and keeping them up to date on new findings via Facebook—has helped make cataloging possible. (Illyenko says, however, that the website isn’t as current as it should be, due to a lack of volunteers.)

Nonetheless, Illyneko says that people are enthusiastic about the project—especially foreigners who visit or live in Ukraine. “It’s very interesting to see in practice how the mosaics are bright in the eyes of others, of people who are not Ukrainian people,” Illyenko says.

On that bright spring day, half a dozen people walk past “Blacksmiths of the Present” and pay it no mind. If they did, they might notice that the vibrant piece both stands out from its gray, nondescript surroundings and is naturally integrated with them. More than 40 years ago, two people—with histories and stories of their own—created this work of art under Soviet conditions, one small, colorful piece at a time. And for more than 40 years, it has decorated the side of this building—as scientists convened inside, as the Chernobyl nuclear reactor exploded, as the Soviet Union broke up.

Which is precisely what makes it worth saving.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook