Why Do Presidents Get Their Own Libraries?

The entrance to the George Bush Presidential Library at College Station in Texas. (Photo: Jujutacular on Flickr)

In May, the Obama Foundation announced that Chicago will be the future location of the Barack Obama Presidential Center, which will include a library and museum. The center will become the 14th institution in the National Archives and Records Administration’s presidential library system, which includes centers dedicated to all presidents from Herbert Hoover onwards.

Over the years, millions of public and private dollars and ostensibly, man hours, have been spent curating these institutions. Which begs the question: why?

Franklin D. Roosevelt began this tradition when, in 1939, he decided to hand over his personal and presidential records to the federal government when leaving office. Two years later, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum was built in Hyde Park, New York to house these records. Before Roosevelt, presidents would take their documents with them when they departed from the White House, leaving them vulnerable to dumping and decay. (An 1819 letter from Bushrod Washington to one-time president James Madison confessed that his uncle George Washington’s presidential documents were “very extensively mutilated by rats and otherwise injured by damp.”)

There are two main components to a presidential library: the library itself and the museum. The library component is essentially a storehouse for a federally mandated data archive—following the implementation of the Presidential Records Act of 1978, presidents must turn over all their records to the National Archives when leaving the White House. Archivists then begin the colossal task of processing documents and electronic files for public viewing under Freedom of Information Act requests, which, if there are no restrictions placed on the relevant documents, can be fulfilled from five years after the president leaves office.

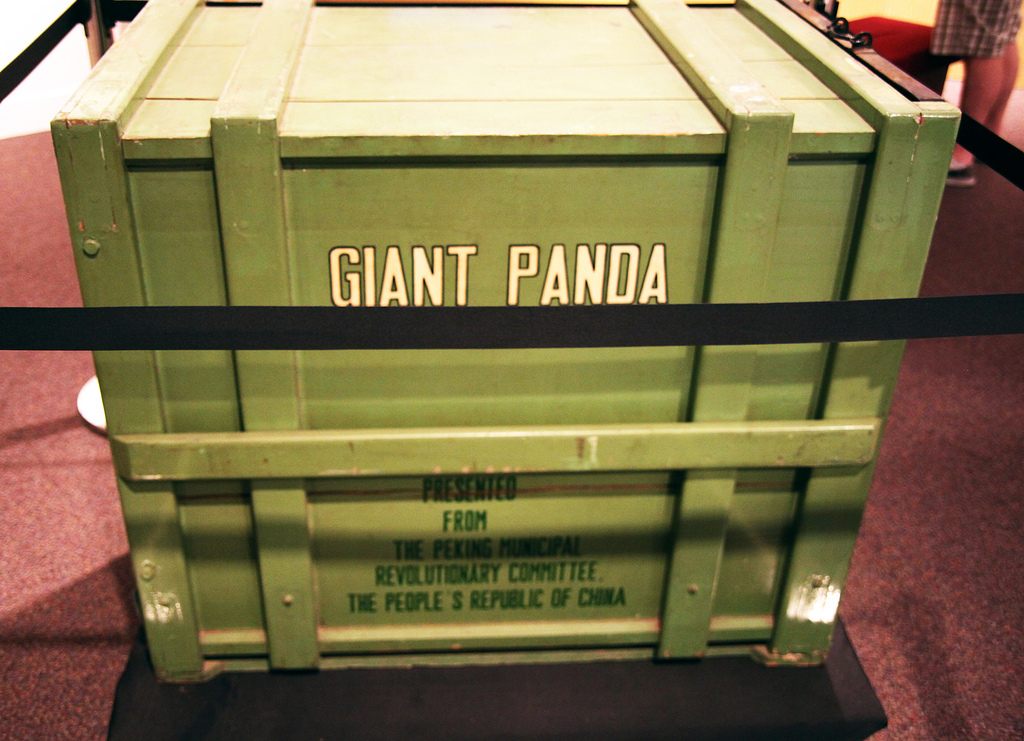

The museum is a different story. This is where you find the fun stuff, such as the wooden bench shaped like Hillary Clinton, the jelly bean portrait of Ronald Reagan, and the crates that held a pair of giant pandas sent from the Chinese to Richard Nixon. The museum is also where you will find exhibits dedicated to showing how strong and bold and brave the president in question was during their administration. Scandals, blunders, and impeachments are sidelined in favor of hagiographic exhibits that together paint a picture of an infallible leader. Because the presidential library is often located in the president’s hometown, there tends to be a “local kid done good” feel, with a bit of generic national pride thrown in. The Herbert Hoover library in Iowa, for example, bills its collective offerings as “the extraordinary story of an orphan boy who lived the American dream.”

A jelly bean portrait of President Reagan, on display at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley, California. (Photo: Ryan Dickey on Flickr)

The positive, patriotic curation approach is inevitable when you consider who puts the museum part of a presidential center together. The creation of a center begins with the establishment of a foundation while the president is still in office. That foundation raises money for construction and endowments—around $500 million, in the case of the George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas—and finds donors to fund exhibits in the museum. The day-to-day administration of the library and museum, however, is handled by the National Archives.

This partnership between the presidential foundation and the National Archives can understandably result in competing interests. When addressing the question of why presidential museums portray the former leaders in such a positive light, the National Archives’s own website, in its presidential libraries FAQ, says that “[t]he composition of the first exhibits in the museums reflect the funding sources of those exhibits.”

In 2011, Larry Hackman, former director of the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum in Independence, Missouri, told the New York Times that “there are hidden and in some cases there are some odious strings that come with that money that keep the library directors, no matter how well intentioned they are, from developing certain exhibitions or programs.”

Hackman faced opposition from Truman’s family and close supporters when pushing for a more critical approach to the president’s use of nuclear weapons, but told the Times that “the process got easier with the passage of time, as family members and supporters began to die off.”

“The depiction of contemporary, or nearly contemporary, events in an exhibit comes with different challenges than the portrayal of events and personalities from a more distant time frame,” the National Archives FAQ says.

A crate that transported a giant panda from China during Nixon’s presidency, on display at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in Yorba Linda, California. (Photo: Tim Evanson on Flickr)

If a president has just left office, and the events of the administration are fresh in the minds of the American taxpayer, said president will definitely want to have a hand in setting the tone of the museum exhibits. One well-publicized example of this is the Decision Points Theater at the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum. In the interactive exhibit, visitors are presented with scenarios from Bush’s presidency, such as the decision of whether to go to war with Iraq and the possibility of bailing out the banks during the sub-prime mortgage crisis.

Multiple-choice buttons offer the opportunity to select a different option than Bush did, but if a visitor decides not to invade Iraq or to let the banks fail, Bush himself appears on screen to explain why that choice is wrong.

Once enough decades have passed, and public sentiment over a presidency has simmered down, museum exhibits may be revised to reflect a more critical approach. But there can still be opposition from die-hard devotees. This was the case at the Nixon library in Yorba Linda, California, which became part of the National Archives network in 2007 after operating independently for 17 years.

The library’s original Watergate exhibit, financed and put together by close associates of Nixon, downplayed the scandal and placed the blame at the feet of the Democrats. In 2011, after years of squabbling between the Nixon Foundation and the National Archives, the revamped exhibit was unveiled. Nixon’s pals were not impressed. Discussing museum director Timothy Naftali’s opening remarks at the exhibit, Nixon devotee Anne Walker wrote:

“I don’t think he missed using one accusatory buzz word; abuse of power, dirty tricks, whitewash, cover up, etc. Several of these same buzz words now scream at the visitors to the Library the President’s friends built. The letters are huge, the colors are bright. No one can miss seeing them.”

Naftali resigned a few months after the exhibit opened. The Nixon library then operated without a director for over three years until Michael Ellzey took up the position in January 2015. In a Los Angeles Times op-ed, Naftali said that the National Archives had found a suitable director in 2012, but the Nixon Foundation didn’t like him and refused to meet with him. The candidate withdrew from consideration.

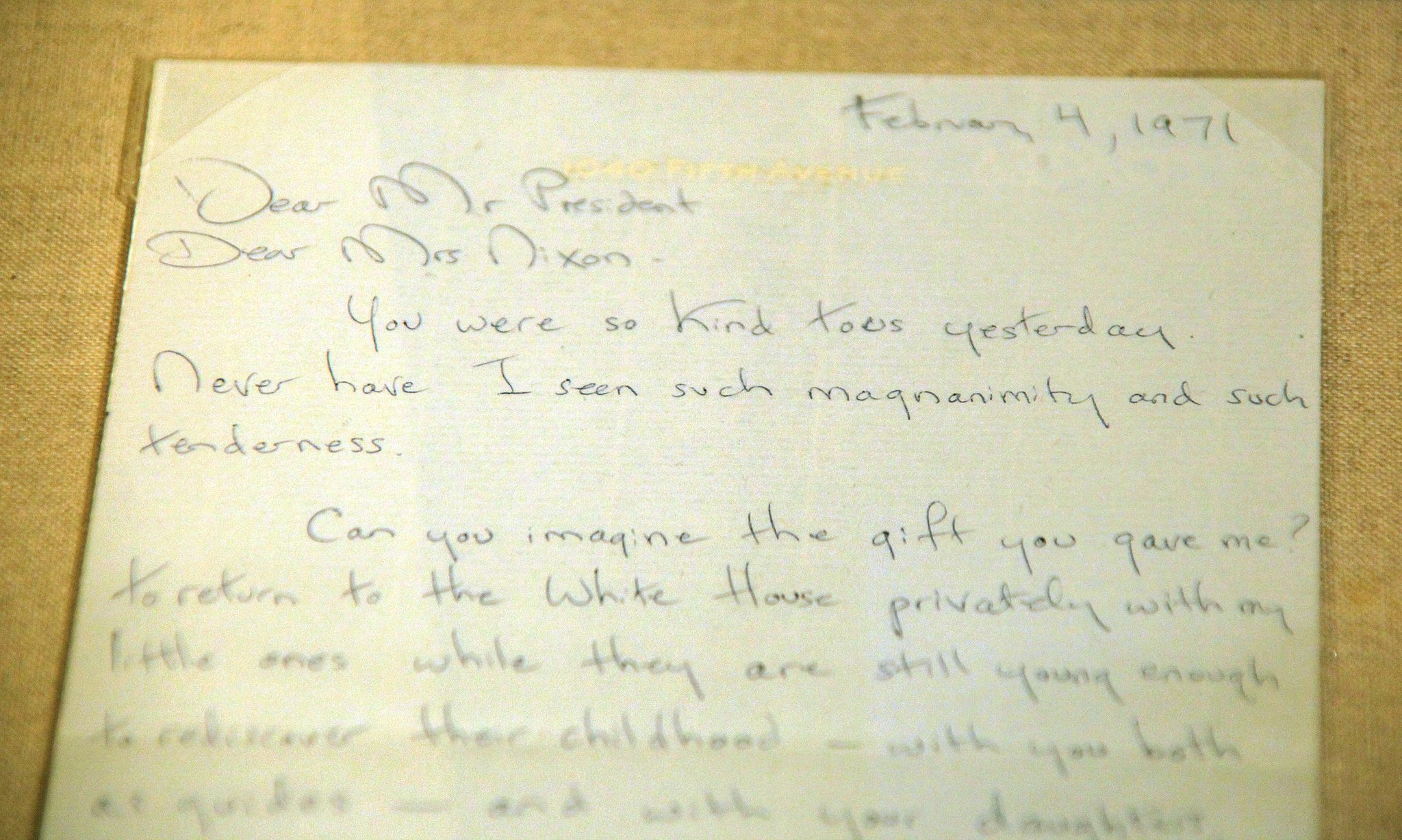

A letter from Jacqueline Kennedy to the Nixons, on display at the Nixon library. (Photo: Tim Evanson on Flickr)

Despite the internal squabbles, the Nixon library offers a good example of how the older presidential libraries are dealing with another problem: how to appeal to the folk who weren’t yet born when the president was in office. The Nixon library is a surprisingly popular location for weddings, with ceremonies held in the rose garden and receptions taking place in the library’s replica of the White House East Room. Events featuring popular political media figures are also held at the library—on June 27, Fox News host Gretchen Carlson will be there to “discuss the rise to hosting her own cable news show, the intense competitive experiences of winning Miss America, the challenges she’s faced as a woman in broadcast television, and how she manages to balance work, family and life,” according to the official event description.

Whether old or new, presidential libraries take advantage of loosely related exhibits to draw crowds—”Football! The Exhibition” opens at the Reagan library in Simi Valley, California on June 6th, while the Lyndon B. Johnson library in Austin, Texas unveils its Beatles exhibition on June 13th. Last year, the George W. Bush library hosted “Five Decades of Style”, an exhibit of fashion designer Oscar de la Renta’s gowns. It was the second time a presidential library hosted a retrospective of the designer’s work: the Clinton library in Little Rock showcased his glamorous dresses in its 2013 exhibit, “Oscar de la Renta: American Icon”. The ball gown angle may seem tenuous, but the de la Renta dresses were worn by several First Ladies—if you want to talk gratuitous fashion items at presidential libraries, you can’t go past the $275 Swarovski-encrusted American flag bracelet at the Reagan library gift shop.

An animatronic LBJ at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum in Austin, Texas. (Photo: Lauren Gerson/LBJ Foundation on Flickr)

So the libraries and museums feature both serious and silly exhibits, but does anyone go? Yes, although the numbers vary dramatically from place to place. Attendance records from 2014 show that the Nixon library ranked tenth out of the 13 presidential libraries, with 85,000 visitors during the fiscal year. The most popular library was George W. Bush’s, with 491,000 annual visitors, followed by the Reagan library at 383,000 and the Clinton library at 334,000. The bottom three were the Truman library, with 59,000 annual visitors, the Jimmy Carter library, with 52,000 visitors, and the Herbert Hoover library, which saw 43,000 visitors during the fiscal year.

The trends are clear: to attract the numbers, a presidential library must be new and/or tied to a president with a solid approval rating. It can be tough for the older institutions to attract an audience, especially when their exhibits are a little dusty, their president is long dead, and the era in which they ruled holds little appeal for researchers and museum-goers. Once a president’s associates have grown old and passed on, the foundation that established their library may struggle to raise funds to support museum exhibits and public programs.

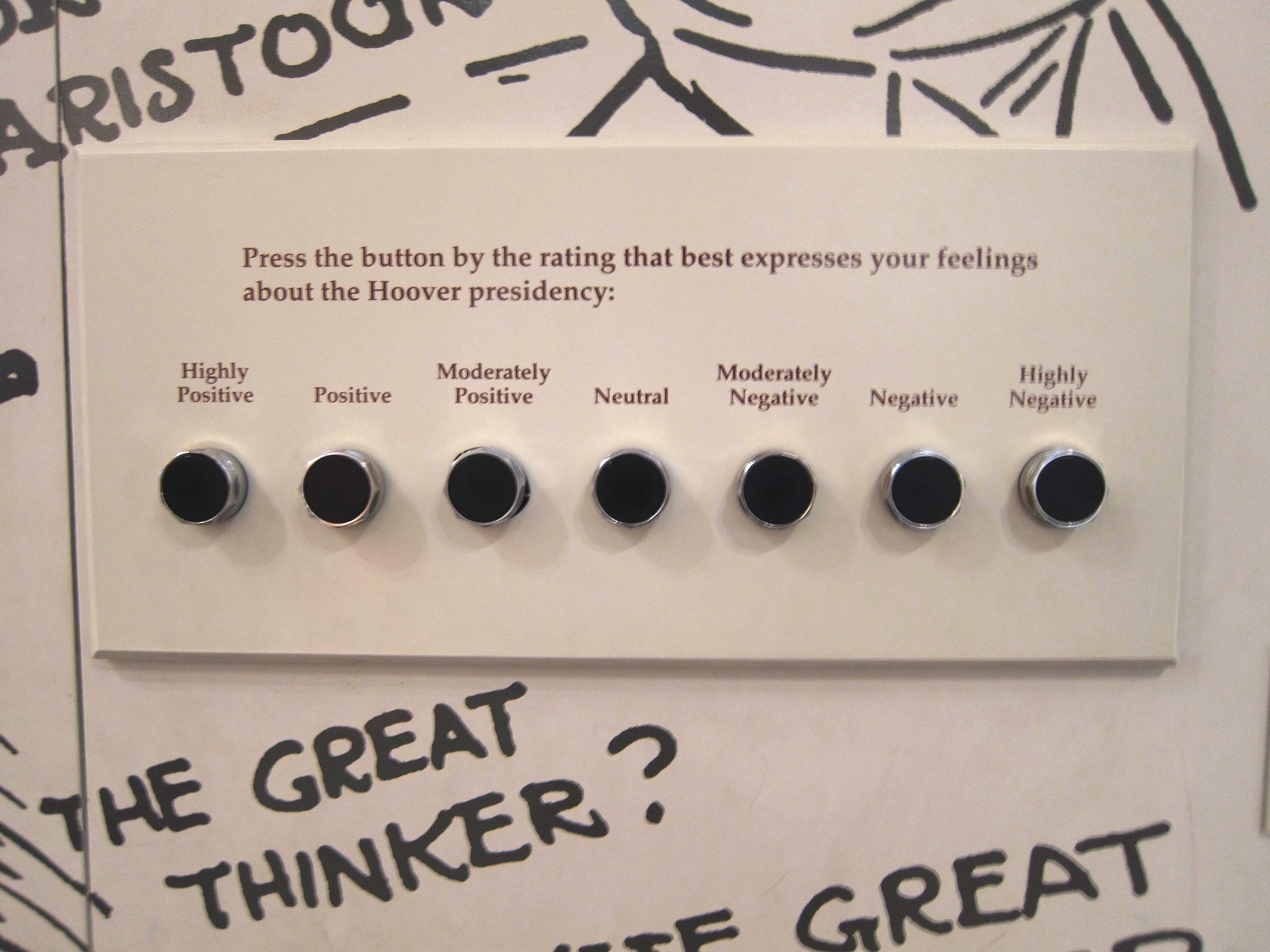

The Hoover museum, established in 1962, recently raised its admission prices for the first time since 2006 in order to make ends meet. It may lack the tech-enhanced pizzazz and LEED-certified architecture of the newer presidential libraries, but the Hoover museum believes in its core message. “His accomplishments as President (and he did have more than a few) were overshadowed by the Great Depression,” says Thomas Schwartz, the director. “But no one can visit this museum and not be struck by the sheer overwhelming sense of awe at Hoover’s tireless efforts at mending a broken world.”

An interactive exhibit at Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in West Branch, Iowa. (Photo: Edward Stojakovic on Flickr)

But worthiness of purpose aside, uneven popularity is one of the reasons that some think that the presidential library system, a mix of public and private funding, is doomed. “Right now, one-quarter of the archive’s budget goes to the presidential libraries,” said United States Archivist David Ferreiro in a 2010 interview with Information Today, “If you look at the projections out to 2030, it does not work. Something has to change.”

There have been a few steps toward reform, such as a 2011 House Oversight Committee hearing and a proposed Presidential Library Donation Reform Act that would require the disclosure of donor names. But an overall solution has yet to be found.

Meanwhile, archivists at the libraries continue processing records every day. Shannon Jarrett, Supervisory Archivist at the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, says the library has thus far released “over 700,000 pages of textual records as well as 27,110 electronic records assets (mainly email and photos).” That sounds like a lot, but there’s much work left to be done. “Our presidential records holdings include over 62 million pages of textual records and 80 TB of electronic records,” says Jarrett, “so we have processed approximately 1.3 per cent.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook