Psychic Archeology, Or How to Dig Up the Dead With Their Own Advice

Frederick Bligh Bond resorted to psychic archeology because he didn’t have permission to dig up the ruins of England’s legendary Glastonbury Abbey. At least this was his explanation for why, on a November day in 1907, he made contact with the spirit of a medieval monk named Johannes.

Over the course of nearly 70 seances, Bond sketched detailed plans of the Abbey, relayed by Johannes, that turned out to be largely accurate. Archaeologists were not pleased with Bond’s methods, but psychic mediums, amateur ghost hunters, and the “dark tourism” industry have capitalized on them ever since.

Glastonbury today is a destination for new-age spiritual seekers, and the idea of solving mysteries with psychic investigation has achieved mainstream success both at tourist sites and in popular television. Though crass sensationalism is the currency of the modern ghost tour game, this couldn’t be further from Bond’s original vision.

A respected architect and historian, Bond developed a genuine belief in the scholarly value of psychic contact with the dead.

Legends about King Arthur and ancient Druid rites have haunted the town of Glastonbury since the 1100s, when the resident monks started promoting Glastonbury Abbey as a destination for pilgrims. In what looks a lot like a modern marketing stunt, they “discovered” the tombs of King Arthur and Queen Guinevere on the monastery grounds, declaring it the site of ancient Avalon.

They set the stage for centuries of tourism; by 1900, those monks were cited as an authoritative source for Glastonbury’s history.

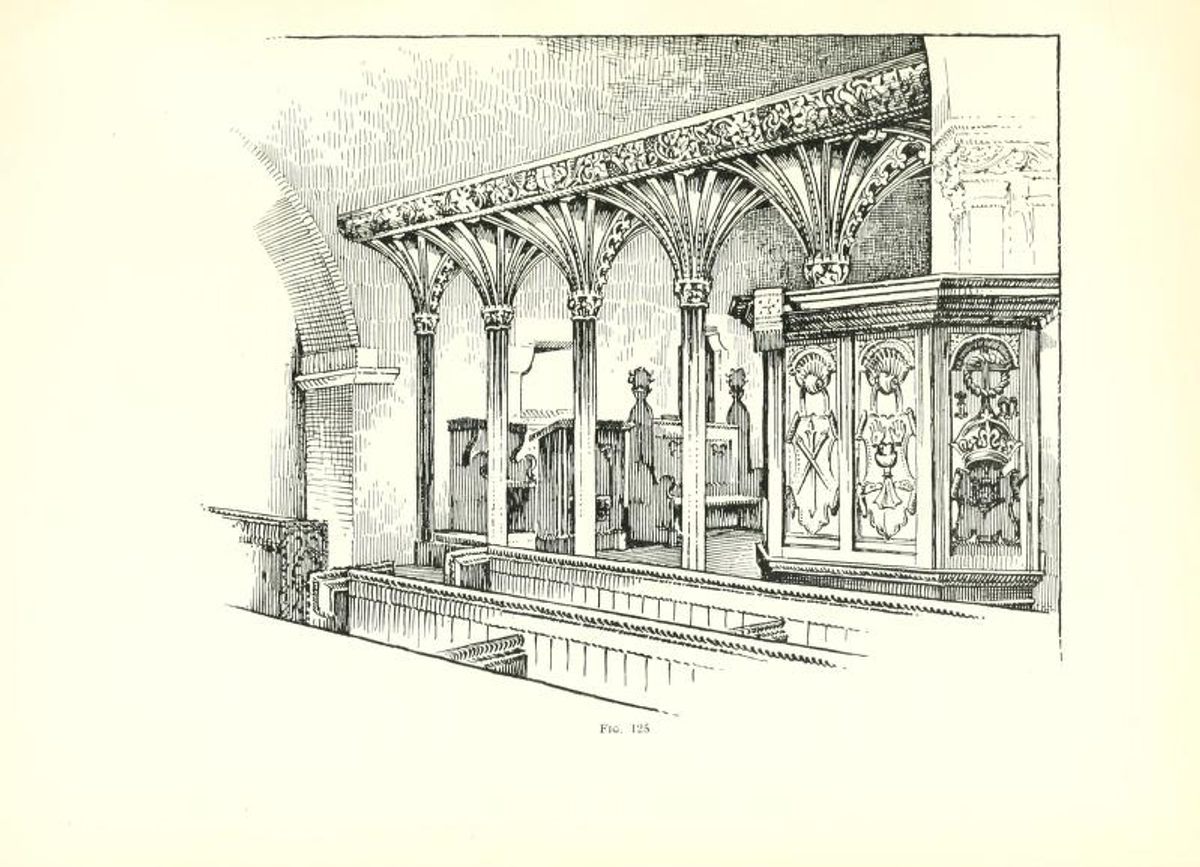

Frederick Bligh Bond waded into this potent blend of fact and fiction intending to set the record straight. A respected architect, he specialized in historic restoration with a focus on medieval British churches. His two-volume scholarly treatise, Roodscreens and Roodlofts, is about the furthest thing imaginable from a flight of supernatural fancy.

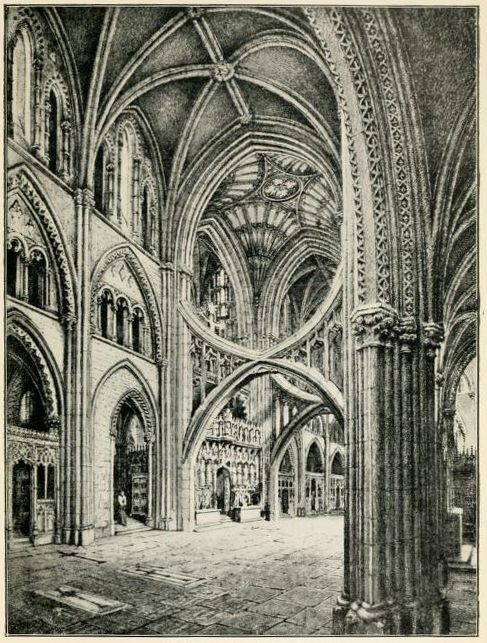

Given his pedigree, Bond was a very good candidate to serve as Director of Excavations at Glastonbury Abbey. Built in the 8th century, the site had since decayed to a few cryptic ruins. The ruins were in limbo in 1900, as the Church of England tried to buy the land from private owners and preserve its heritage.

Unable to break ground, but eager to begin the job, Bond spent months scouring local archives for plans and records of what the storied monastery actually looked like. Growing frustrated with incomplete and inconsistent sources, he sat down in his office with a friend and fellow scholar, John Allen Bartlett, who proposed a different method: automatic writing.

In this practice, a person acting as medium enters a state of relaxation or trance and allows their hand to inscribe messages which appear to come from the spirit world.

Many respected scientists and intellectuals at the time saw automatic writing as an interesting psychological phenomenon, perhaps caused by secondary, unconscious personalities. Bond, going a step further, thought it a promising tool for a “psychological experiment”: regardless of who was talking through the medium’s hand, they might reveal secrets left out of the archives and buried below the soil. That first afternoon, Bartlett, in a “passive” mental state, held a pencil over a sheet of paper, ready to channel messages from within or without.

Bond began with the question, “Can you tell us anything about Glastonbury?” In response, Bartlett’s pencil produced what might serve as the slogan of psychic archeology: “All knowledge is eternal and is available to mental sympathy.”

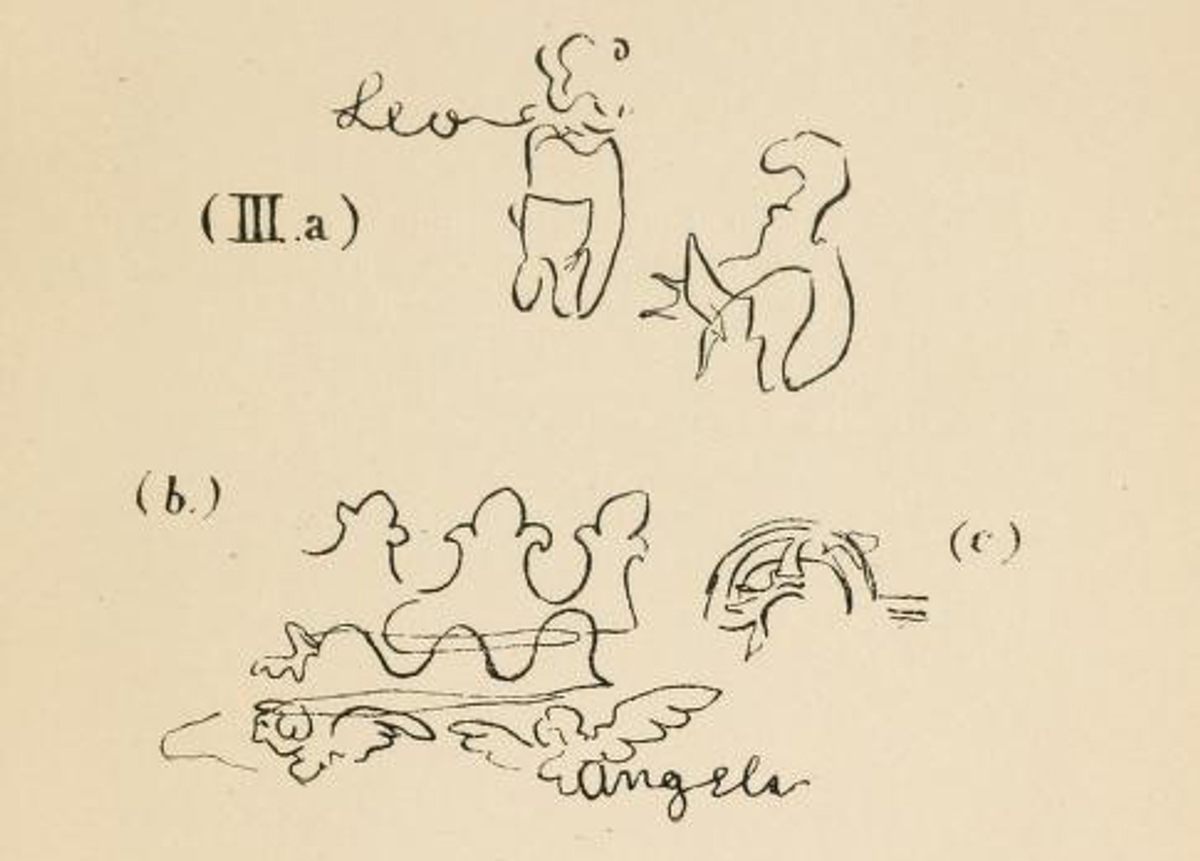

A torrent of communication flowed from the spirit world in garbled Latin over the following months, and it provided very specific answers to Bond’s archeological conundrums. It also introduced Bond and Bartlett to the colorful personality of Johannes, a 16th-century monk who enjoyed fishing and ale.

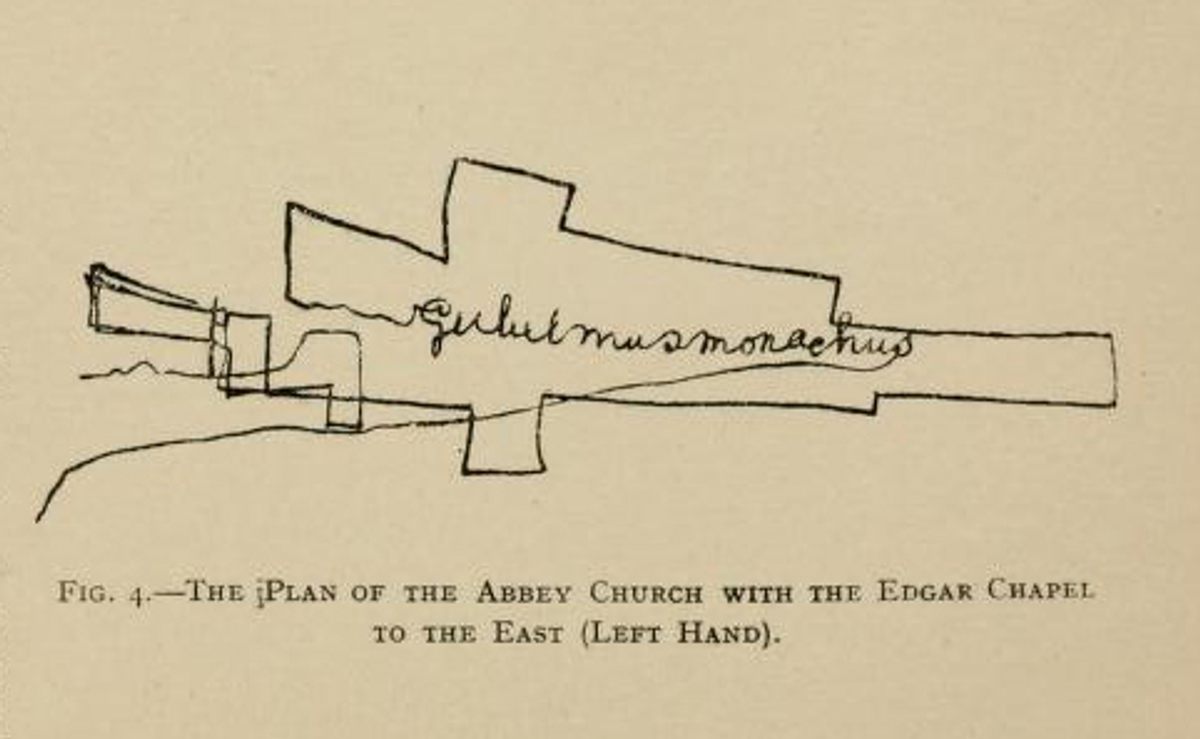

Extensive descriptions and drawings of the abbey emerged under Bartlett’s hand, which Bond attributed to “a species of telepathic action” that linked Bartlett’s mind with a “storehouse or treasury of past knowledge,” in this case represented by an inebriated monk. On the sixth sitting, Bond asked the spirits directly, “Where should we dig?” Johannes answered, “The East end. Seek for the pillars…the foundations are deep.”

In May of 1908 Bond finally got permission to start excavating. His advance knowledge of the abbey’s floor plan meant that “scarcely a spadeful of earth was wasted.” He immediately located the lost Edgar Chapel that lay where Johannes had suggested.

For the next decade, Bond studied and published on the Abbey’s architectural features; his sophisticated technical work is still respected today. He only revealed his initial source to a few close friends. In addition to fears about professional scandal, he knew that the Church of England would not smile upon spirit-communication perpetrated at a holy site.

Things might have continued this way if Bond hadn’t published a book about Glastonbury that swerved from meticulous archeology into the realm of metaphysics. The Gate of Remembrance presented Bond’s grand theory of a collective unconscious, “a larger field of memory, a cosmic record,” which historians had to access as part of their mission to understand the past.

The book told the whole tale, including séance transcripts and a thorough explication of psychic technique. Maybe Bond hoped to profit from popular interest in ghosts and the occult, but for the most part it looked like career suicide driven by genuine conviction that he had discovered a larger truth.

The Gate of Remembrance took into account psychological explanations for supernormal phenomena. Bond acknowledged that Johannes might be a phantom of his own unconscious mind. After all, Bond already knew everything there was to know about medieval churches, so perhaps the creative freedom of the séance helped him step back to see how pieces of the puzzle fit together. He certainly saw automatic writing as a method only suited for the trained imaginations of experts.

However, the book ultimately made a much stronger claim. Bond believed that automatic writing was a direct link to a collective consciousness that transcended time and space. He called this the “Great Memoria,” a “cosmic record” of all human experience and history. Unlike religious notions of the afterlife as a place of rest, reward, or punishment, Bond envisioned a giant psychic archive of great practical value to archaeologists.

Bond’s professional reputation was built on hard evidence–digging in the dirt, examining stones, tracing foundations. Archeology at this time was just entering its professional stage, asserting itself as a scientific discipline rather than an antiquarian hobby. Colleagues, therefore, were not pleased with Bond’s insistence that ultimate knowledge of the past lay in the psychic, rather than the material, realm. He was promptly removed from his position as Glastonbury’s chief excavator, and his private architecture business dried up as well. In 1926 Bond fled the wreckage of his career and sailed for the United States.

In America, Bond’s high standards of proof doomed his attempts to make a living as a psychical investigator. Wealthy American spiritualists bankrolled his work for many years, but when he insisted on exposing their favorite medium as a fraud, they withdrew their support and sent him back to England in financial ruin.

Despite its many skeptics, the concept of psychic archeology proved impossible to dislodge from the discipline’s fringes, reappearing in sensational cases every few decades with Frederick Bligh Bond cited as its founding authority. Archaeologist Philip Rahtz famously called Glastonbury “the mecca of all irrationality,” a paradise for “hippies, weirdos, drop-outs, and psychos.”

The fringe practice pioneered at Glastonbury has spread to tourist sites around the world; countless cities promote entertaining ghost tours based on purported revelations from the dead. Encountering a “presence” from the past can be far more engaging for some visitors than reading a history book. The knowledge that it’s part of a rehearsed spectacle competes with the thrill of a first-hand experience to produce a tantalizing sense of possibility.

Bond tried to bring that sense of expansive possibility into the realm of scientific fact. His standard of proof was different from that of spiritualists in his time, and probably from most modern ghost tours: psychic archeology was supposed to go beyond sensational apparitions to develop a deep and meaningful connection with “that greater field of thought and experience which we term the Past.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook