When Quackery on the Radio Was a Public Health Crisis

In the 1920s and 30s, regulators and experts grappled with how to stop the sale of dubious devices and miracle cures over the airwaves.

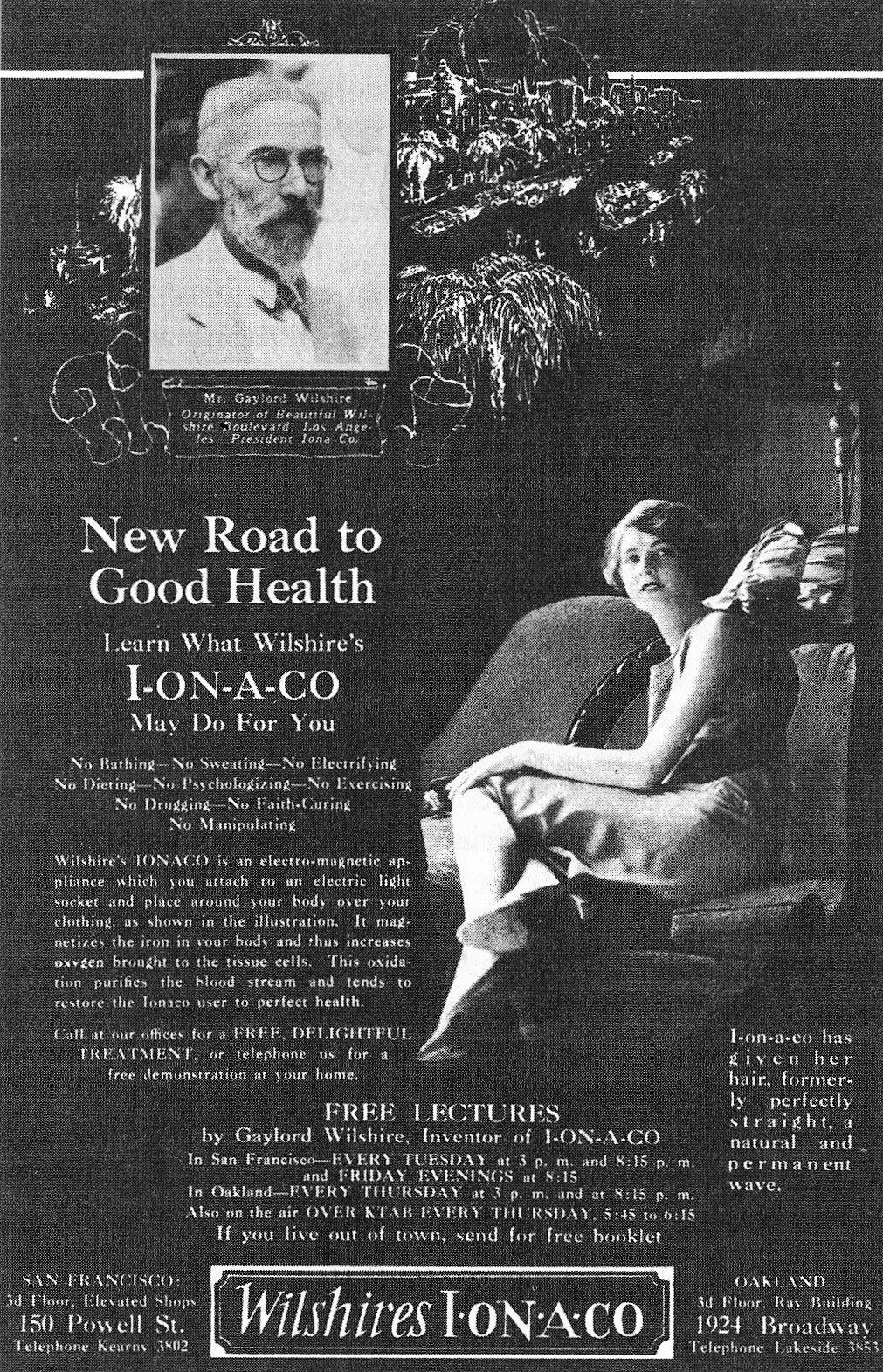

It’s no wonder that the I-on-a-co tempted listeners who heard the spiel crackle through their radios. The insulated coil wrapped around the body like a hug and jiggled with electric current. All you had to do was slip on the leather loop and let the magnetic field work its vaguely science-y magic.

The gadget promised to deliver you from back pain, infections, and arthritis. “No bathing—no sweating—no electrifying—no dieting—no psychologizing—no exercising—no drugging—no faith-curing—no manipulating,” one print ad swore, alongside an image of a woman lounging on a couch in a slinky dress, her painted lips parted just so. For $3.50, the contraption was a direct, no-fuss path to self-improvement.

To spread this snake oil gospel, the inventor, Gaylord Wilshire, knew he needed to get his message into American living rooms. He took out a nearly full-page ad in the Los Angeles Times in 1926, which included a schedule of upcoming radio promotions so people could hear fawning testimonials first-hand. Wilshire held court on the airwaves, a standing Thursday-evening spot on San Francisco’s KTAB.

Who could say no to an easy cure for most any pain, to a better life—no strings attached?

By 1930, more than 45 percent of American households had a radio, and that share nearly doubled by the end of the decade. More homes were equipped with radios than with telephones, and in that mass of listeners, quacks and faddists found an attentive audience. Radio frequencies were lousy with voices spouting unfounded medical advice and shilling nostrums that pledged to ramp up virility or relieve everything from aches and pains to stomach troubles and listlessness. There was a potion or magic machine for anything that plagued you.

For decades, the American Medical Association (AMA) and other trade and professional groups had waged campaigns to evict advertisements for quack treatments from journals, newspapers, and magazines. Coupled with state and federal legislation that cracked down on false advertising, the AMA’s efforts to shame outlets that amplified these hollow promises paid off.

The association “mercilessly exposed” medical journals that refused to boot patent medicine ads, writes archivist Eric W. Boyle in Quack Medicine: A History of Combating Health Fraud in Twentieth-Century America. “It is not creditable—in fact, it is positively brazen—for a medical journal, supposedly published in the interest of the medical profession, to place such advertisements before its readers,” JAMA editor George H. Simmons had concluded.

By the 1920s, Boyle writes, the AMA had helped curb the nostrum trade in dozens of medical journals, and their efforts rippled out into the lay press, too, as newspapers imposed more rigorous standards on the medical advertisements they ran. But regulations lagged in the newer medium of radio, where chicanery boomed.

Scores of stations, such as WAM in Newark, New Jersey, advertised junk contraptions such as the Theronoid, which emulated the I-on-a-co. The mechanism was vague, but the promises bold: a cure for everything from asthma to arthritis, insomnia, sciatica, high blood pressure, and varicose veins. The Federal Trade Commission ordered the company to stop portraying their product as a cure for anything, but the larger problem of fraudulent medical advertising didn’t disappear, even as the government rolled out a smattering of laws to govern radio licenses.

In 1932, the Federal Radio Commission (later supplanted by the Federal Communications Commission), banished from the airwaves fortune-tellers, mystics, seers, and other people peddling dubious claims, but concern remained about what was fit to air and how to enforce rules about truth in advertising. A 1936 edition of Hygeia, a publication of the AMA, lamented that “no adequate and prompt measures are as yet available to curb venal radio stations from selling ‘time’ to anyone who pays the price.”

And when regulators did catch up with fraudsters, enterprising quacks got creative. By setting up towers and transmitters in small towns south of the United States/Mexico border, a phalanx of fabulists launched their own stations, beyond the reach of many regulations.

These supercharged stations, known as “border blasters,” weren’t the exclusive domain of quacks and psychics. Precursors to televangelists delivered booming sermons about the ravages of drink, and music was in heavy rotation, too. Mexican and vernacular songs leapt across geographical and cultural boundaries. A border-blaster station carried ditties by June Carter into Johnny Cash’s Arkansas home, Gene Fowler wrote in Oxford American, introducing the country icon to the woman who would become his collaborator and wife.

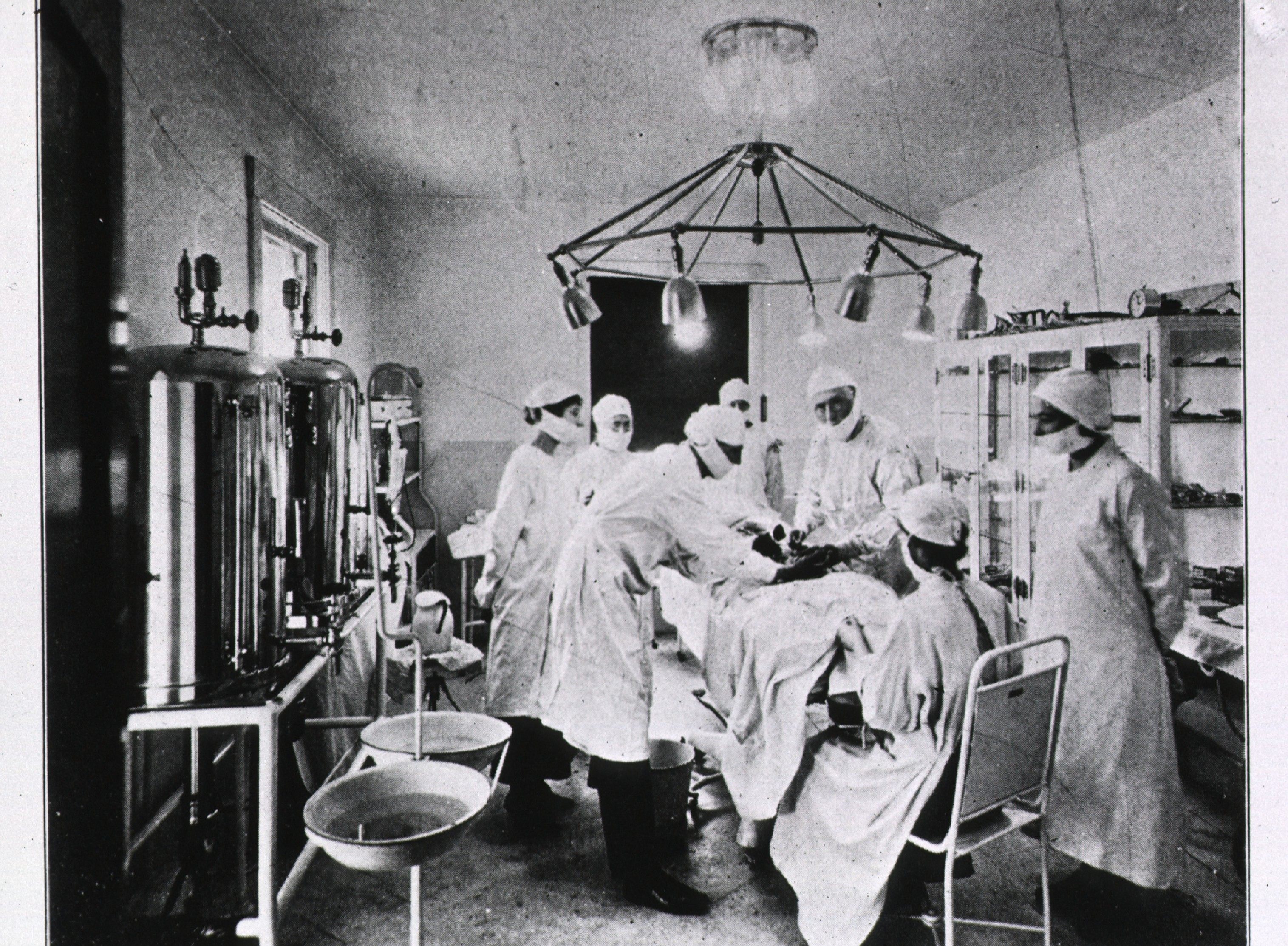

But quacks with something to sell were among the most ambitious and active border-hopping radio pirates. Chief among them was John R. Brinkley, who became (in)famous for transplanting slices of goat gonads into human testicles, with the promise that the graft would fuse with the patient’s existing equipment and supercharge his bedroom activities.

Brinkley wasn’t a trained doctor—he nabbed a degree from a diploma mill, and was eventually stripped of his license—but he really did keep a herd of goats and was indeed slicing people open. When the AMA checked in on his Kansas clinic, observers concluded that his surgical work was actually rather swift and tidy. But despite his broadcast testimonials, the surgery did nothing at all.

Brinkley’s boastful radio orations drew both clients and the attention of regulators. He was among the first broadcasters to have his radio license yanked by the Federal Radio Commission.

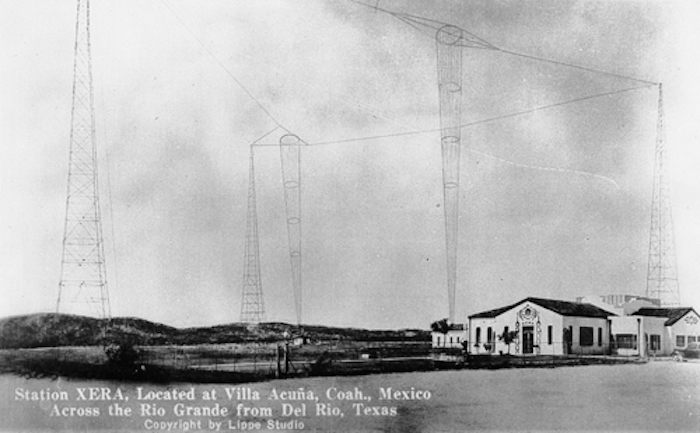

So Brinkley moved down to Texas and launched a powerful station across the border in Villa Acuña, Mexico. Authors Bill Crawford and Gene Fowler describe the station’s staggering reach in their book Border Radio: Quacks, Yodelers, Pitchmen, Psychics, and other Amazing Broadcasters of the American Airwaves. “While most radio outlets in the United States broadcast over transmitters with about 1,000 watts of power,” they write, “border stations boomed their programming across America with transmitters humming at as much as 1,000,000 watts.”

The AM stations could reportedly be heard, sometimes quite clearly, as far away as Finland and New Zealand. “Birds flying near antennas would get zapped” and tumble from the sky, dead, Crawford told NPR’s Fresh Air. There are tales of listeners tuning in from barbed wire fences or metal bed springs.

One of Brinkley’s contemporaries was Norman Baker, a former vaudevillian who put his showmanship to work to sell patent medicine. Baker didn’t need the imprimatur of a fancy institution or degree: On the airwaves of his station, KTNT, which beamed across the Midwest, Baker played the role of a booming populist who could convince listeners that he was on their side by sandwiching his quackery between agricultural reports and music.

He pitched listeners a cancer cure, but, according to the historian Eric Juhnke, author of Quacks and Crusaders: The Fabulous Careers of John Brinkley, Norman Baker, and Harry Hoxsey, one former employee testified that the potion was actually a cocktail of clover, corn silk, watermelon seed, and water.

When his exaggerations finally baited regulators and his station was shut down, Baker, too, moved his operations to Mexico. Border stations sprouted in Ciudad Juarez, Monterrey, Piedras Negras, and more. In his Brinkley biography, Charlatan, Pope Brooks notes that so many broadcasters clustered in Eagle Pass, Texas—a town just across the border from one station—that they formed a baseball team.

If the U.S. government couldn’t mute purveyors of the unproven, untested, and ineffective—from within or from over the border—it could help the listening public learn to navigate medical claims with more skepticism.

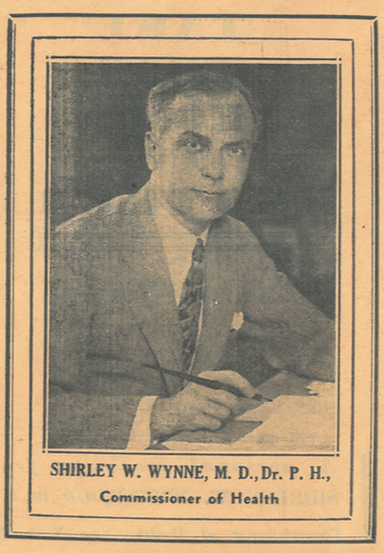

“Quackery has taken a new lease of life in the radio,” noted Shirley W. Wynne, then the New York City Commissioner of Health, in a letter dated June 1931. Wynne was responding to a letter from a physician complaining about the baseless advice and ads for schlocky devices floating into American homes. Many such complaints drifted across Wynne’s desk—so many, in fact, that today city archivists have dozens of sheafs of them spanning 60 years that they are currently processing under a National Endowment for the Humanities grant.

Wynne even broadcast a message of his own, warning listeners of New York City’s WEAF that legions of charlatans and faddists were doubly dangerous because they seemed, at face value, to be trustworthy. “These fellows, who not long ago found themselves banished to the kind of magazines and newspapers you would not allow in your homes, now find direct access to your family circle through the radio,” Wynne said. They commandeered a medium considered respectable, and that also broadcast advice from reputable doctors. By turning a knob, Wynne added, “you may tune in(to) a bona fide health talk, or you may open the door instead to an insidious quack.” The latter exuded confidence and authority, which polished their claims to a sterile sheen.

It was easy to be duped, so Wynne laid out a checklist of red flags. Anyone who failed to spell out his or her qualifications, affiliation, and address was due for scrutiny. An “ethical physician,” Wynne said, would have nothing to hide.

Another antidote was critical thinking. Listeners ought to be skeptical of testimonials, he said, and about indiscriminate cure-alls. Marvelous gizmos and contraptions should rouse suspicion, too. A trustworthy physician, Wynne added, would never promise results, since health is impossible to guarantee.

Wynne’s office had successfully muzzled a few culprits, and appealed to the Federal Radio Commission for help. The officials also corresponded directly with stations, such as Newark’s WAM, that advertised elixirs and gimmicks including the Theronoid. “There is no apparatus that can be hung around a person’s neck that can cure or prevent disease,” Wynne wrote in one brusque letter to the station’s managing director.

Writing in The Pentagraph, a newspaper in Bloomginton, Illinois, in October 1930, the physician William Brady paraphrased Wynne’s call to arms and cautioned that “honest folk must now beware of the healers on the air.” With “medico-merchants … tainting the air,” Brady wrote, Wynne’s counterattack “has done the people of the whole country a great service.”

Farther south, stations like Brinkley’s were besieged by lawsuits from both sides of the border. The Mexican government revoked XERA’s license in 1939. (The call sign has since been bestowed on a new station, and a handful of other border-blasters beam signals between the United States and Mexico even today, but the DJs aren’t spinning snake oil.)

There’s still no cure for the desire for a quick fix from the fringes of science. Since Brinkley went off the air, clever salespeople have made use of hotlines and digital marketplaces, and federal agencies have scrambled to legislate them—from the Psychic Readers Network hotline of the 1990s to Goop’s current cabinet of dubious wellness curiosities.

It’s not hard to imagine why people buy into these schemes, in search of a sliver of a silver lining. Wynne recognized that impulse in his radio address nearly 90 years ago. The sick and the scared aren’t entirely to blame for being swayed by radio quacks or today’s versions of miracle cures. “Persons who are ill with a chronic disease are always eager … to be convinced that they can be cured, and cured speedily,” Wynne said. When survival and success are the prizes, suspension of disbelief isn’t such a big ask. But, he added, the ability to sniff out truth from lies is itself a survival skill.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook