‘Rappin’ Max Robot,’ the First Hip-Hop Comic Book

With the help of Keith Haring, Eric Orr created the four-issue series in 1986.

Today the hip-hop industry and all it entails—music, clothes, concert tickets—is a multi-billion dollar industry, but in the early 1970s until the early 1980s it was a real DIY affair. DJs and MCs hit community-center parties; dancers did their moves in clubs, not videos; and visual artists made their way via grassroots, rather than galleries.

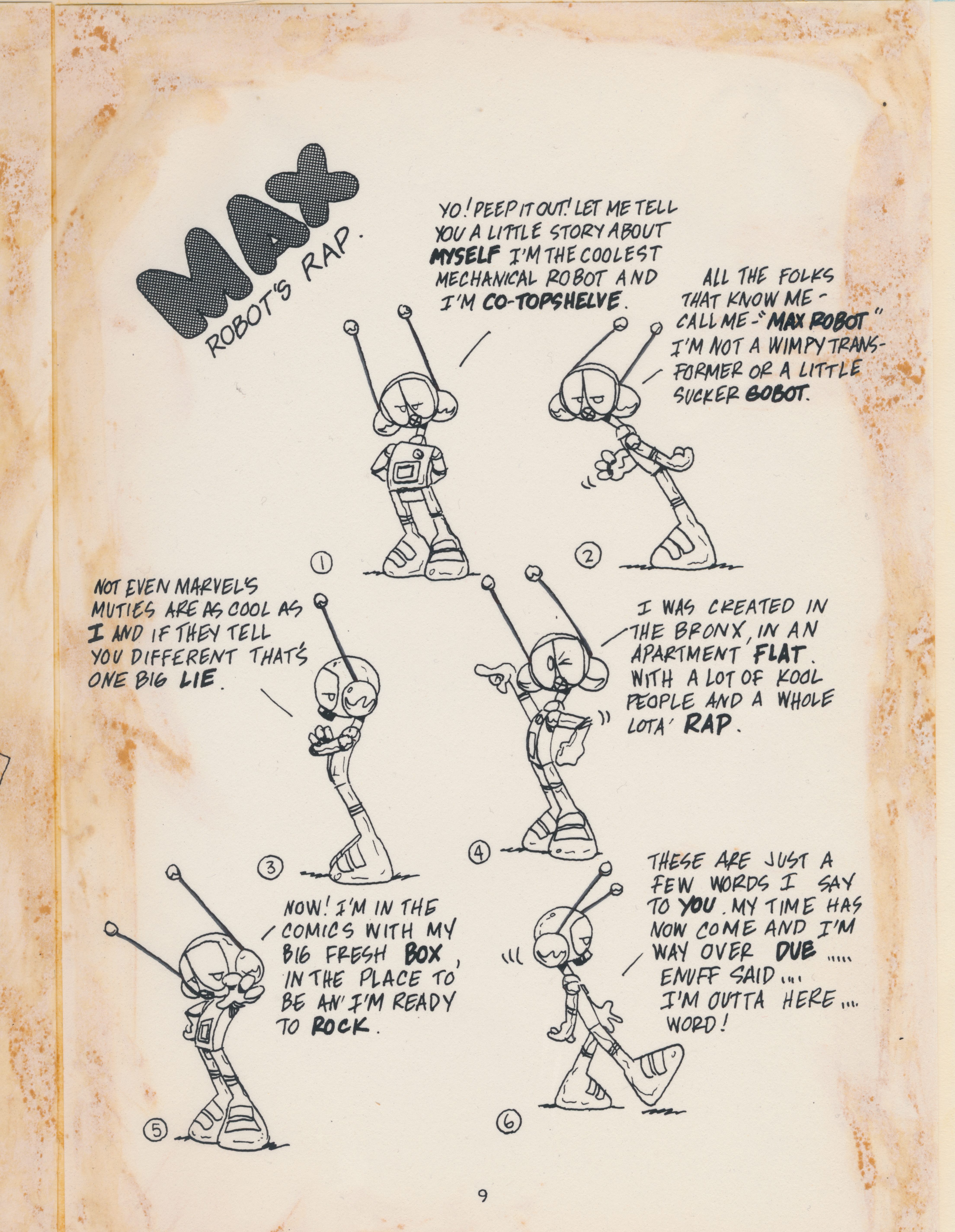

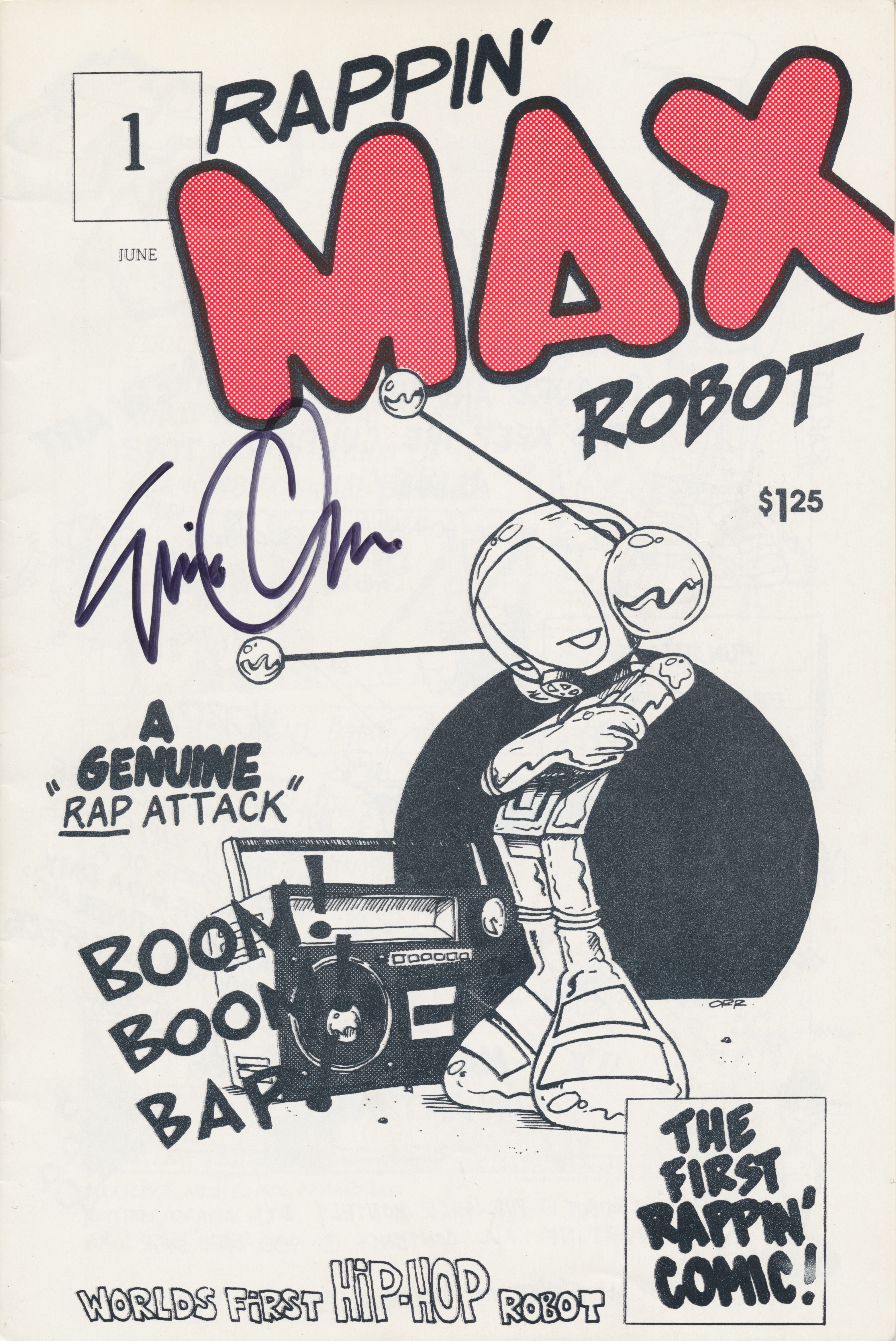

It was in this spirit that in 1986, Bronx artist Eric Orr published his comic book Rappin’ Max Robot, a comic for and about the hip-hop community that is widely acknowledged as the first hip-hop comic book.

Orr had an early love for comic books, and would sneak the Sunday comics into church with his brothers. The first comic-style drawing he did was of Charlie Brown. “I gave it to my aunt, and she hung it up right away,” says Orr, “which gave me the positive reinforcement to keep on drawing.” He kept drawing all through school, making up stories and drawing sketches and comics for his friends. It’s probably a common origin story for a lot of artists, but something else was happening around Orr: The Bronx was birthing a whole new sound.

The pioneer era of hip-hop was from 1973 until about 1983, explains Cornell Hip-Hop Collection curator Benjamin Ortiz. “But within that decade, around 1979, the recording industry starts to record ‘rap’ music in studio, play it on the radio, make videos.” At the time Orr’s comic came out, “there’s a split,” says Ortiz. “There’s endorsements, media, big companies like Def Jam getting off the ground, but the vast majority who are active still in the community making noise, doing creative things—events, grassroots level, community level. People were trying to figure out the possibilities of the form.”

At that time, Orr was drawing his soon-to-be signature robot head icon all around his neighborhood, but it was just a rough idea at that point. It wasn’t until a chance meeting that the robot became something way bigger.

“I was walking in the neighborhood one day, and I heard someone call out ‘Orr. Hey, Orr!’” It was one of Orr’s high school classmates, John. After high school, John had gone into the music business, and under his stage name Jazzy Jay was one of the pioneers of hip-hop, who later started his own label called Strong City. Jay, a DJ and producer, needed a logo design, and he hired Orr for the job. As the Strong City label grew, Orr moved into an art-director role, developing logos and artwork for golden era hip-hop artists. It was there that Orr was able to develop his robot character. “I noticed that in the [comics] marketplace, there wasn’t anything speaking to the hip-hop community,” he says. “I decided to do it myself.”

Orr’s vision was to create a comic focused on album releases, graffiti, and music. But getting the comic to print was going to take some work and some help. As Orr’s portfolio grew, so did his reputation. In 1982, he met New York artist Keith Haring, and the two became friends. Two years later, the pair collaborated on a series of drawings that appeared in New York City subway stations. When it was time for Orr to rally his friends and family to get the first issue of Rappin’ Max to print, Haring was one of Orr’s calls. “Keith Haring bought an ad on the back page of comic book and helped fund the first printing along with other family and friends,” Orr says. “I was able to go to a local Bronx printer and printed 500 copies.”

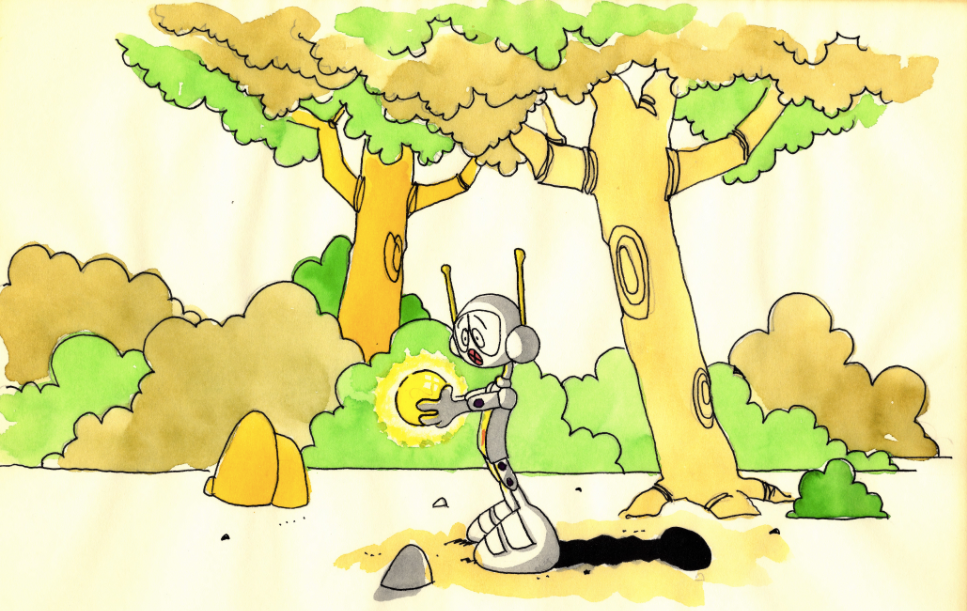

The first issue was released in 1986 and it featured our robotic hero in scenes from the city: rap battles, hearing the latest release on his boombox, and letting dealers know he was a strictly drug-free robot. Ads for local businesses—a record store, a video store, a pizza shop—all filled the pages of issue one, each of them playing a part in getting Rappin’ Max’s comic debut from Orr’s imagination onto the page.

Distribution was also DIY: “I walked around to all of the comic stores.” Orr’s effort paid off, and the first issue sold out in a month. It even garnered some press attention including coverage in the New York Daily News. The hip-hop community, which he had in mind all through the project’s creation, was responding to it. Orr produced three more issues, although with some changes. The first issue was styled like a traditional comic book, but the later three issues, produced in a fold-out style, took their inspiration from the zine International Graffiti Times, another homegrown New York City publication that documented street art and hip-hop culture around the world.

Orr’s four-issue run was an important part of the growing hip-hop scene of the 80s. “There wasn’t anything else out there like it,” Orr says. “We were all young, all hungry. The movement was new. There weren’t that many major players at the time.”

Orr’s archives found their way to Cornell’s collection a lot like the way Orr found his way to Jazzy Jay: by chance. The library had just acquired the archives from performer and producer Afrika Bambaataa, and in cataloging the items, they came across a copy of Rappin’ Max. They reached out to Orr soon after. “Part of [hip-hop] culture is the underground, the obscure. If we were to focus on the things that made the most impact or money, that would be against our mission,” says Ortiz. The comic book, he continues, “cuts across various academic fields: publishing, music, art. It provides a time capsule for east coast hip-hop.”

Rappin’ Max and Orr have gone far beyond those early sketches. Orr’s work, including Rappin’ Max have appeared as customized X-box face-plates at the E3 Expo, limited run t-shirts for companies in Los Angeles and Osaka, and in exhibits at the Queens Museum, China Heights gallery in Sydney, and the Hotel Des Arts in San Francisco, among others. Orr has also used Rappin’ Max as a teaching tool in workshops for kids.

Orr has also been a frequent Comic-Con panelist discussing the intersections between comics and hip-hop, but he fondly remembers those early days: “The climate back then was DIY, no one would do it for you. Cats were selling records out of their trunks, under their arms. It was organic. You did it because you loved it, man. You loved it because you wanted your friends to say you were doing something cool. That was all the acknowledgement we needed.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook