How One Man and His Dog Rowed More Than 700 Kākāpōs to Safety

In the late 19th century, Richard Henry laid a blueprint for modern conservation in New Zealand.

In 1893, in Auckland, New Zealand, 48-year-old Richard Henry was going through a peculiar midlife crisis. It wasn’t for any of the usual reasons, such as a failed marriage (though he had one) or a failed career (though he had been chasing a dream job for several years), but rather it was over his obsession with flightless, moss-colored parrots called kākāpōs. Henry had observed the birds’ steep decline after mustelids, such as ferrets and stoats, were introduced to the country, and had spent much of the previous decade trying to convince scientists that the birds were in real danger of going extinct, write Susanne and John Hill in the biography, Richard Henry of Resolution Island. But Henry, who did not have traditional scientific training, went unheard by scientists. On October 3, a deeply depressed Henry attempted to shoot himself twice. The first shot missed and the second misfired, and Henry checked himself into the hospital, where doctors removed the bullet from his skull.

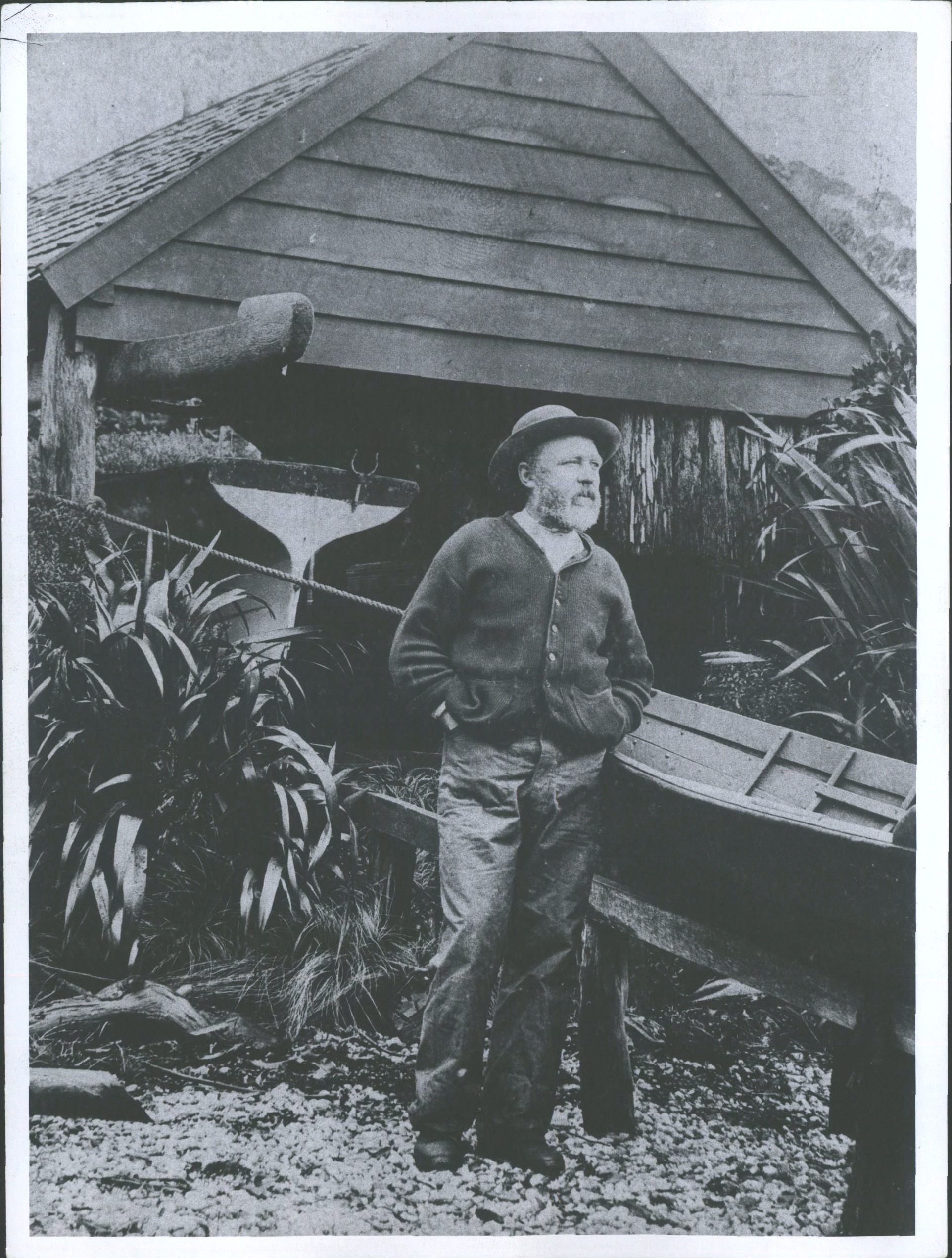

Several months later, Henry got that dream job: caretaker of Resolution Island, an 80-square-mile, uninhabited hunk of rock off southern New Zealand that he hoped to turn into a predator-free sanctuary for kākāpōs and other native birds. For the next 14 years, he toiled away alone on the island in pursuit of this revolutionary conservation idea. He rowed hundreds native birds from the mainland, across choppy waters, to keep them safe from the snapping jaws of furry little predators.

Despite his pioneering vision, Henry was rarely taken seriously as a conservationist in his lifetime, and after he died, he became a tragic footnote in New Zealand’s archives of conservation. “He was a visionary, a bit of a recluse, and a hermit,” says Andrew Digby, a kākāpō conservation biologist with the New Zealand Department of Conservation. “But he was so far ahead of his time, and had a lot of things right that other people didn’t.”

Henry was the first to understand the kākāpōs’ erratic breeding patterns and behavior, and his scheme for Resolution Island laid the blueprint for one of the country’s major modern conservation initiatives. This year, New Zealand hopes to restart Henry’s long-abandoned project and actually turn Resolution Island into a kākāpō sanctuary.

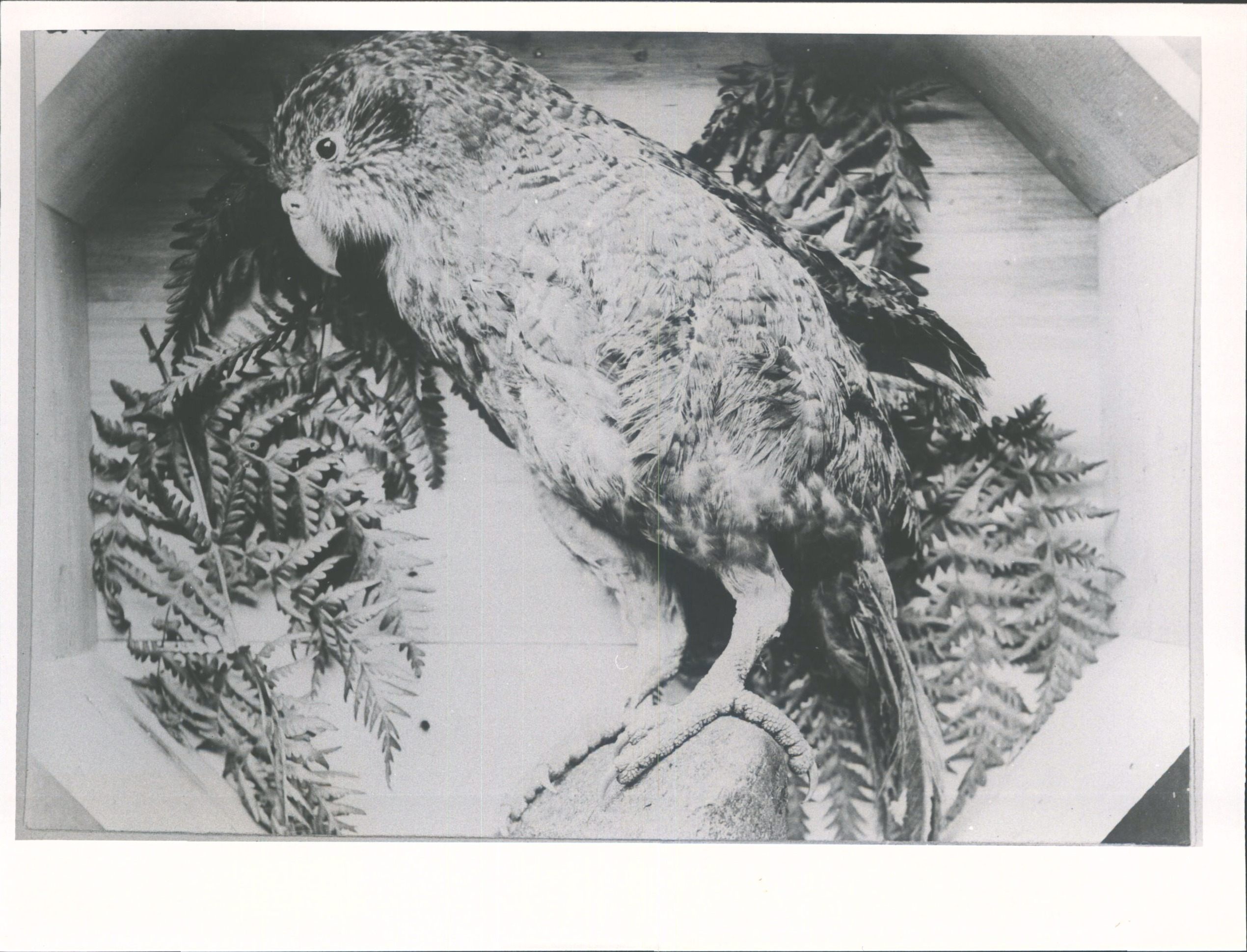

Henry, who was born in Ireland, went to New Zealand with his family in 1851 to escape the potato famine. He worked odd jobs: machine repairman, gardener, sawmiller, shepherd, carpenter, rabbiter, bird collector, and taxidermist. As the latter, he would stuff and sell any of New Zealand’s large, flightless birds, but the amiably chunky kākāpō was far and away the easiest prey. The birds smelled like papaya, had no fear of humans, and abounded across New Zealand, utterly without defenses. Before New Zealand was colonized by Europeans, the Māori hunted the unusual parrots for meat and turned their feathers into lush, colorful cloaks called kākahu. Scottish explorer and surveyor Charlie Douglas once wrote that you could shake a tree and kākāpō would fall like fluffy green apples. On one hunting expedition in the 1880s, Henry watched a flightless weka bird (a rail about the size of a chicken) maul a kākāpō that had eaten so many broadleaf shoots that it could barely waddle away.“They are the easiest thing in the world to exterminate,” he wrote in a letter to a friend, according to the Hills’ biography.

In the 1860s, rabbits were introduced to New Zealand as a game animal, and soon multiplied into a nightmare. They razed meadows, killing tens of thousands of sheep with nothing left to graze on. In 1876, two men in the town of Invercagill requested five pairs of weasels to fix the problem. Scientists raged against the idea but shepherds rejoiced, and in 1882 the government began releasing torrents of weasels, ferrets, and stoats.

Almost immediately, birds began disappearing. First to go were the large, brown wekas, then the Picasso-colored paradise ducks, and then many of the kiwis and kākāpōs. Henry’s years of hunting plentiful birds had morphed into a kind of love, and he tried to warn the public about their plight. The government, slow to act and reluctant to spend, finally designated Resolution Island as a wildlife reserve in 1891 and apportioned funds for a curator. The requirements were both daunting and almost nonexistent—the person just had to be willing to live alone for years. Just seven people applied. In 1894, a few months into his hospital stay, Henry got the job.

Resolution Island is a harsh kind of wild: densely wooded mountains and rugged cliffs fringed with wind-sculpted alpine scrub. “It feels like being on the edge of the world,” Digby says. The weather can be just awful, with squalls blowing more than 70 miles per hour and more rainy days than not. “It’s a really, really wet place,” he adds. “Not to mention the sand flies.” The surrounding fjord, Dusky Sound, is dangerously choppy, probably rough enough to sink a swimming stoat. The island made a perfect potential bird sanctuary.

In 1895, Henry began the painstaking job of catching enormous parrots from the mainland and rowing them across Dusky Sound. His fox terrier, Lassie, sniffed the birds out (while wearing a muzzle), and Henry followed the sound of the dog’s bell. “Lassie was the first-ever conservation dog,” says Erica Wilkinson, a threatened species ambassador for the New Zealand Department of Conservation. Lassie did sometimes accidentally frighten or maim the birds, but her nose led Henry more than 500 of them over six years. Once found, the birds were not hard to catch. Henry could just grab them and stuff them into a knapsack to transport them to pens. “He originally had one big pen, but then he found out the kākāpō tend to severely attack each other in close proximity,” Wilkinson says. As Henry collected the birds, he took copious notes about their breeding behaviors, noting that the birds gathered to breed every two or four years—something scientists argued over as late as the 1980s, the Hills write.

While the birds were under his care, Henry fed them oats, gooseberries, and blue peas. The birds also loved to chew their way through the cages he held them in. One unhappy bird chewed through so many cages that Henry felt obliged to release him, the Hills write. Securing one kākāpō per day was good, any more was dumb luck. Once Henry had caught enough to justify a dangerous voyage to the island, he put the birds in cages and waited for the rain to clear. “He nearly died several times rowing these birds backwards and forwards,” Digby says. “He’d get caught in a squall and his boat would fill with water and the kākāpō would drown.”

Henry’s plan was chugging along until March 4, 1900, when tourists on a boat passing through Dusky Sound told him they’d spotted a weasel chasing a weka on the beach. Henry, in a state of disbelief, wrote in his diary that it almost sounded like a joke, the Hills write. Henry then spent 91 days attempting to catch the animal. Six months later, he saw a stoat himself, and knew the great experiment of Resolution Island would soon be over. In the coming years, the newly established population of stoats would eventually kill every surviving kākāpō Henry had arduously rowed to Resolution. He remained for eight more years, moving more than 700 birds in total, before growing more frustrated and ornery and eventually resigning his post, the Hills write. No one continued his project, and when he died in 1929, only the postmaster attended his funeral.

In 1975, the conservationist Don Merton was on a quest to find a kākāpō in the mountains of Fiordland, the mainland coast closest to Resolution Island. Scientists were unsure then whether the kākāpō had gone extinct. All the birds they captured and moved into conservation facilities in the 1960s had died in captivity. But Merton’s tracking dogs had picked up a scent and cornered a kākāpō against the edge of a cliff. He dove, caught the bowling-ball-sized bird, and named it Richard Henry, according to New Zealand Geographic. Scientists estimated that bird Henry was born in the 1930s—the last kākāpō known to have survived on the mainland.

Scientists spirited Henry to Maud Island, called Te Hoiere in Māori, a predator-free reserve off New Zealand’s North Island. Soon after, a population of fewer than 200 birds was discovered on Stewart Island, southwest of Resolution, that was declining quickly due to cat predation. Over the next few decades, scientists moved every known kākāpō to Maud Island, Codfish Island, and Little Barrier Island, north of Auckland. Henry went to Maud, where he soon found a female kākāpō from Stewart Island named Flossie. The pair had three chicks: Kuia, Gulliver, and Sinbad, all of whom hatched in 1998. Henry was later moved to Codfish Island.

Henry’s Fiordland genes provided invaluable genetic diversity to the Stewart Island population’s limited gene pool. “Genetically, he was invaluable,” Digby says. “He saved the species,” Wilkinson adds. In 2016, Richard Henry’s grand-chick, Henry, was born. Henry’s offspring do look different from other kākāpōs. “They have more bulging eyes,” Digby says. In the 2019 breeding season, more than 86 chicks hatched in total—a new record.

On Christmas Eve, 2010, the second Richard Henry was found dead on Codfish Island, according to the country’s Department of Conservation. He was an old bird, more than 80 years old, it’s thought, and had gone blind in one eye. Just a few months earlier, Merton spent a few days with the frail, deteriorating Henry to say goodbye, Jane Goodall writes in Hope for Animals and Their World. When Henry died, there were 121 kākāpōs.

Today, there are 211 of them, each with a name and an electronic transmitter that allows researchers to monitor their activity. The birds now all live on three sanctuary islands: Codfish and Little Barrier, as well as Anchor Island. The first two are predator-free. Though Henry’s strategy of translocation was controversial in his lifetime, it now forms the backbone of modern kākāpō conservation, Digby says. “The great tragedy of Richard Henry is he didn’t get to see this legacy that he left us, how he laid the blueprint for new wildlife sanctuary islands,” Wilkinson says. “He thought of himself as a failure.” The separate island populations also help protect against disease, critical in a population with so little genetic diversity.

Kākāpō conservation is currently undergoing a paradigm shift, Digby says. “Kākāpō are one of the most intensely managed species on earth, and we’re beginning to step back more and more.” There are actually so many kākāpōs now that scientists are looking for a new island to act as a home. “One of the places we’re thinking of putting them next year is Resolution Island,” Digby says. There are still stoats on the island, but the scientists hope to set out a fierce barricade of traps and actively manage the predator population to get it as close to zero as possible. The first birds to enter Resolution will likely be males, which tend to be bigger and better able to defend themselves.

Meanwhile, New Zealand has set an ambitious goal to rid the entire country—composed of the two big islands and hundreds of smaller ones—of every stoat, rat, and possum by 2050. It’s a herculean task, but Wilkinson is optimistic. “We have small predator-free havens all around the country,” she says. “As soon as there’s a weasel, everything shuts down.” Henry’s dream was never just to see kākāpōs thriving on Resolution, but to see them back in New Zealand.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook