Ritualistic Cat Torture Was Once a Form of Town Fun

Are you an evil omen? (Photo: Ralph Daily/flickr)

If you’re fond of cats, you should probably stop right here and switch to looking at photos of kittens wearing tiny hoodies. Because in medieval times, kitties were significantly more likely to end up in bonfires than on Buzzfeed, and what you’re about to read is not pleasant, unless you happen to despise cats with a sadistic passion.

In the 15th century, Edward, Duke of York, declared that if any beast possessed the devil’s spirit in him, it was without doubt the cat. In medieval Europe, the cat was seen as representing evil, witchcraft, vanity, and even female sexuality, vestiges of which remain to this day (there’s one P-word in particular).

The only way to rid something of evil, of course, is to burn it or bash it to bits. So that’s what folks did to cats. In Ypres, Belgium, for instance, townspeople hurled cats from a belfry onto the cobble streets below and then set them on fire. The event, called Kattenstoet (Festival of Cats), still takes place every year on May 2, though since Ypres’ questionable form of pest control ended in 1817, it now involves stuffed animals as proxies.

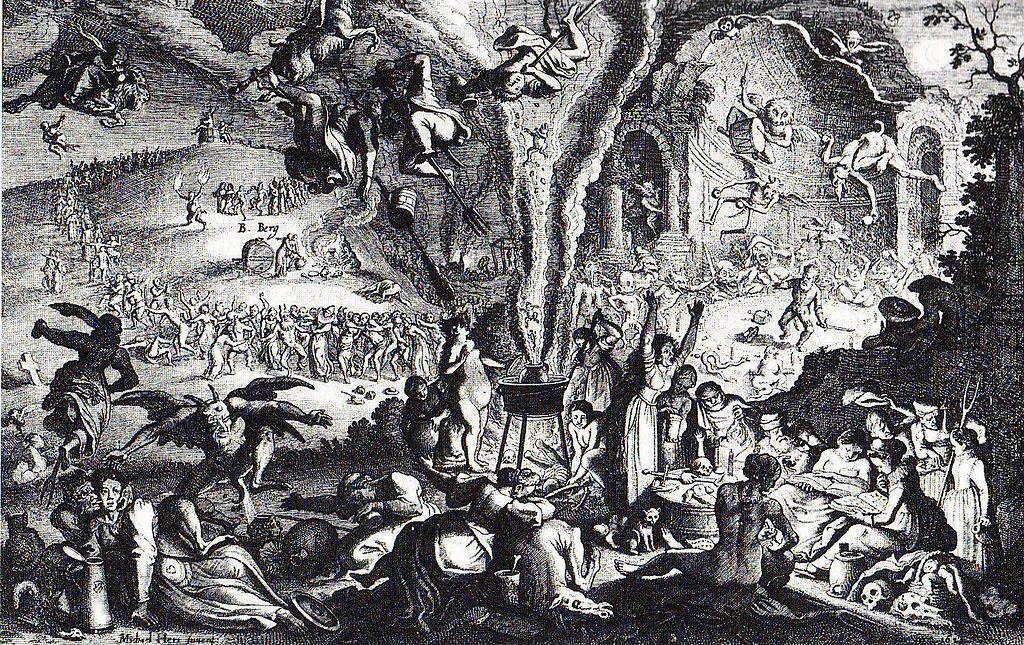

17th century witchcraft and evil. The best way to protect oneself? Kill cats. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Again, second chance to stop reading if you really really like cats. Here, look—funny cat memes! These notably involve cats not being tortured, at least in the traditional sense.

If you’re still reading, then hello, glad to have you here. Curiosity is about to kill a lot of cats—cats thrown in bonfires, beaten in barrels, and tossed high into the air with no safety net beneath. In his captivating book Fox Tossing: And Other Forgotten and Dangerous Sports, Pastimes, and Games (parts of which a very sensitive reviewer for the Wall Street Journal described as “repulsive for a cat lover”), Edward Brooke-Hitching catalogues three pastimes coming at the expense of cats, enjoyed at the time by schoolchildren, town dignitaries, and even Louis XIV himself, who kindled the annual cat-burning bonfire (feu de joie) in 1648, to great delight. Brooke-Hitching says that it’s interesting to see things that were once accepted now considered barbaric, though he’s had to clarify a few times that he didn’t write about what he calls the “cat-based cruelty sports” while rubbing his hands with glee.

Dogs were not the only ones to torture cats. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

That brings us to the pastime of cat-burning (brûler les chats), which is exactly what it sounds like. It was a form of medieval French entertainment that, depending on the region, involved cats suspended over wood pyres, set in wicker cages, or strung from maypoles and then set alight. In some places, courimauds, or cat chasers, would drench a cat in flammable liquid, light it on fire, and then chase it through town. The embers and charred bits of cat from these blazes would be collected and taken home for good luck. Purrrrty ugly.

(French cats, incidentally, had it tough for another few hundred years—in the 1730s, there was the Great Cat Massacre, a Paris killing spree in which bourgeois-hating workers murdered their masters’ cats out of spite.)

What are cats thinking? We shall never quite know. (Photo: Melissa Wiese/flickr)

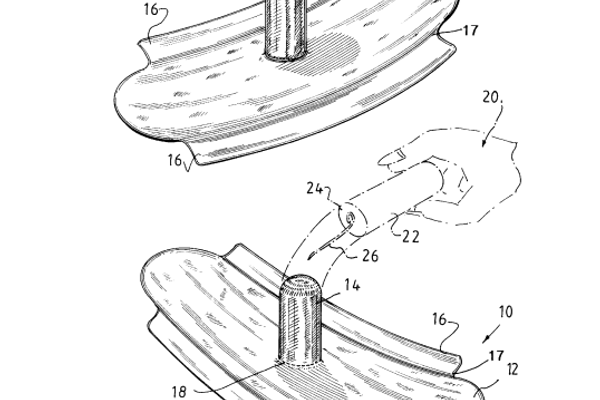

Another feline torture sport, “Beat the Cat Out of the Barrel,” comes to us from medieval Denmark’s Carnival, or Fastelavn, a celebration of the start of Lent. BCOB, as it was never called, was a family activity meant to purge evil omens; a black cat was believed to embody the spirit of winter, and before spring could arrive, it had to be banished. A cat fitting the color qualification would be stuffed into a barrel that was hung from a tree (think: piñata) and beaten with sticks until the wood shattered; once the cat tumbled out, it was at risk of being further beaten if it didn’t scamper away quickly enough. A Cat Queen and Cat King would be crowned based on battering performance.

Danes still honor this superstitious ritual today, continuing to crown Cat Queens and Kings. Nowadays, it’s more of an actual piñata, the cat having been swapped out for candy. But participants still paint a cat on the outside of the barrel for good measure.

Witchcraft at work. Quick, burn some cats! (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A third cruel cat sport, and the most grisly so far, comes from the fair grounds of 17th-century Italy, where an unlucky cat would be nailed to a post or tree, and spritely young men with hands bound behind their backs would take turns kneeling in front of it and slamming into it with their foreheads. It seems like straight brutality, but it also involved some strategy, since the cat could still lash out with its claws. The cat did not generally fare well.

Zoosadism was widespread throughout the last millennium in such forms as pig-sticking, monkey-fighting, eel-pulling, and octopus-wrestling. But why were cats so particularly well represented?

Witches have long been associated with cats. This 16th century witch is feeding her familiar spirits. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Witches have long been associated with cats. This 16th century witch is feeding her familiar spirits. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

According to historian Robert Darnton, cat torture was seen as the one remedy to protect against sorcery; by breaking the cat, you broke its malevolent power. Cats were ingredients in both witches’ brews and folk medicine, and to make yourself invisible, at least in Brittany, you were told to eat the still-warm brain of a just-killed cat. In more than one folktale women who consumed cats in stews gave birth to kittens.

But was this fear and hatred bred from something else? Irina Metzler, in her article “Heretical Cats: Animal Symbolism in Religious Discourse,” shares the idea that it was the cat’s independent nature that gave humans their anxiety.

Cats, it seems, will forever wield some odd power over us—but mercifully, we are no longer as inclined to torture them en masse.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook