Is This Your Last Chance to ‘See Rock City’?

The Southern roadside attraction is thriving, but its iconic barn-top billboards are fading away.

Before “going viral” was a good thing, the most successful advertising campaigns met customers where they were. For those with personal vehicles in the mid-twentieth century, that place was the American road. And among the most memorable billboards in the country in that era were those painted on the sides and roofs of barns through the South directing drivers to “See Rock City.”

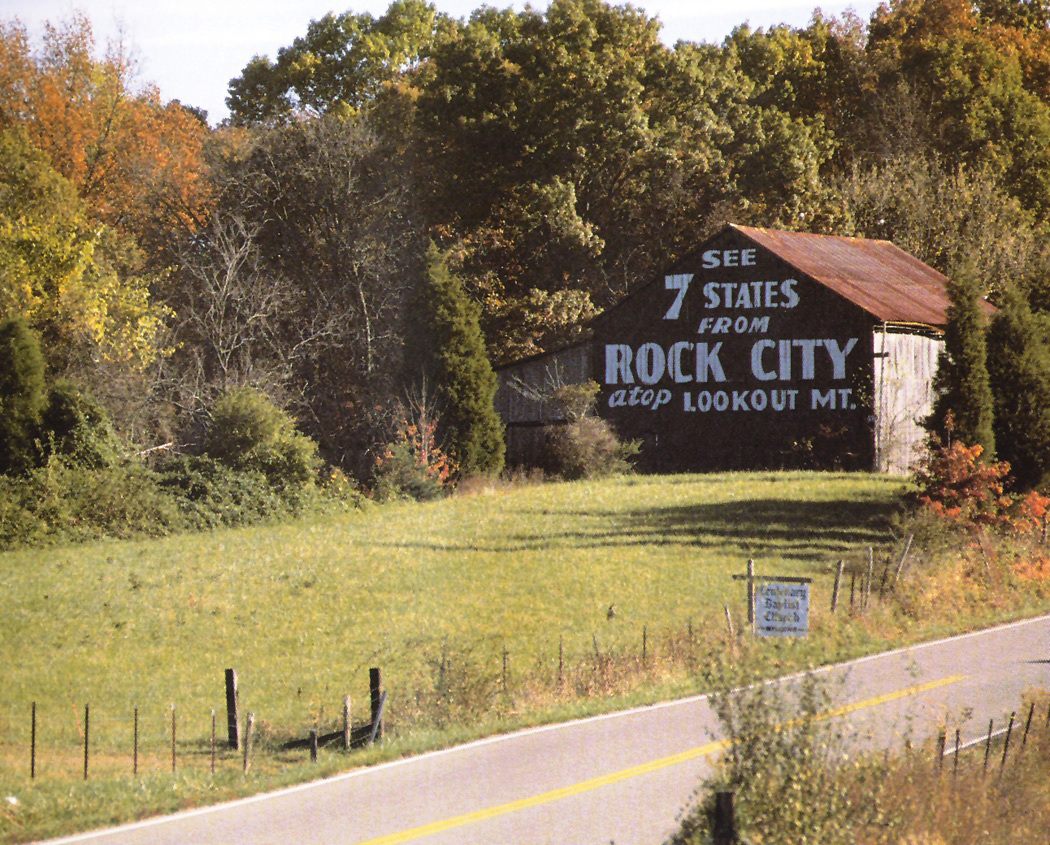

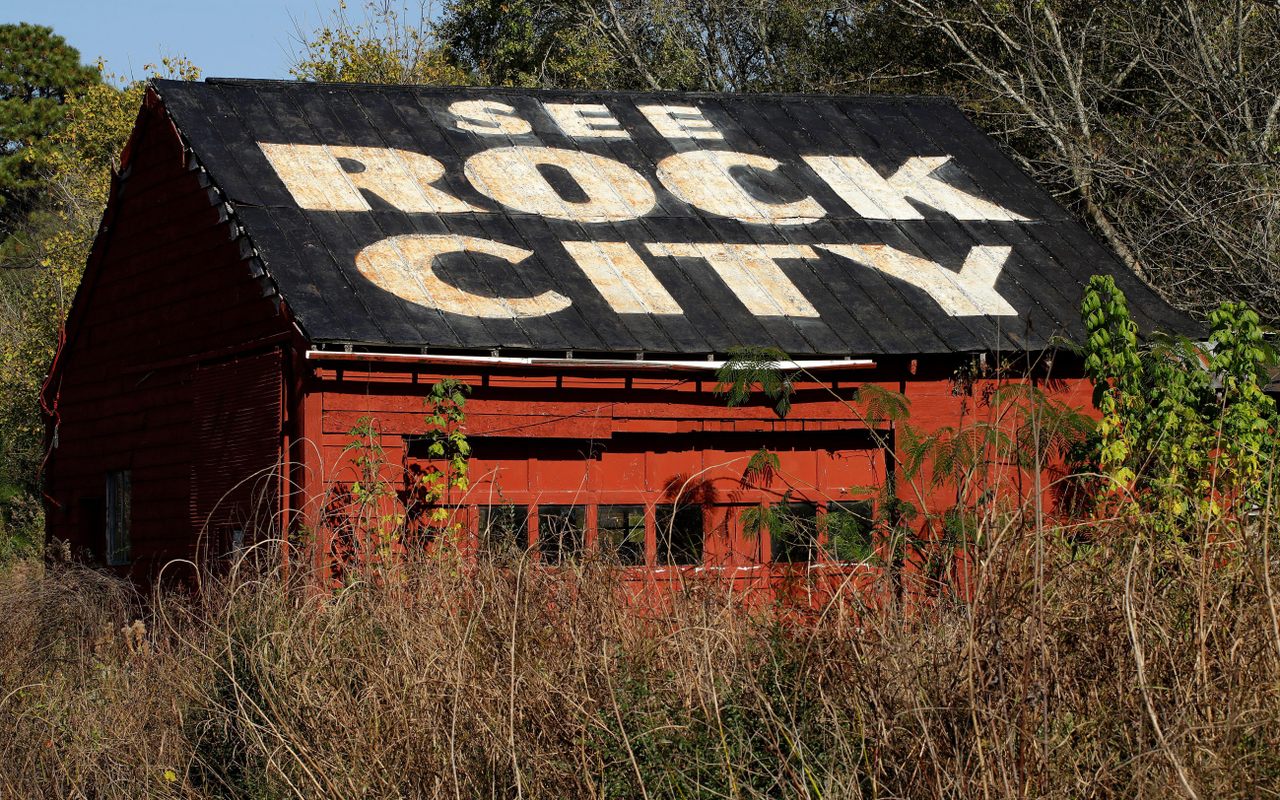

The Rock City barns became almost as famous as the unusual landmark itself, not unlike the hand-painted billboards for ice water at Wall Drug that dot the upper Midwest or the mysterious The Thing signs that line I-10 through the Southwest. But due to a variety of factors from natural disasters and age to legislation and a lack of skilled sign painters, these slices of Americana are now at risk of disappearing entirely.

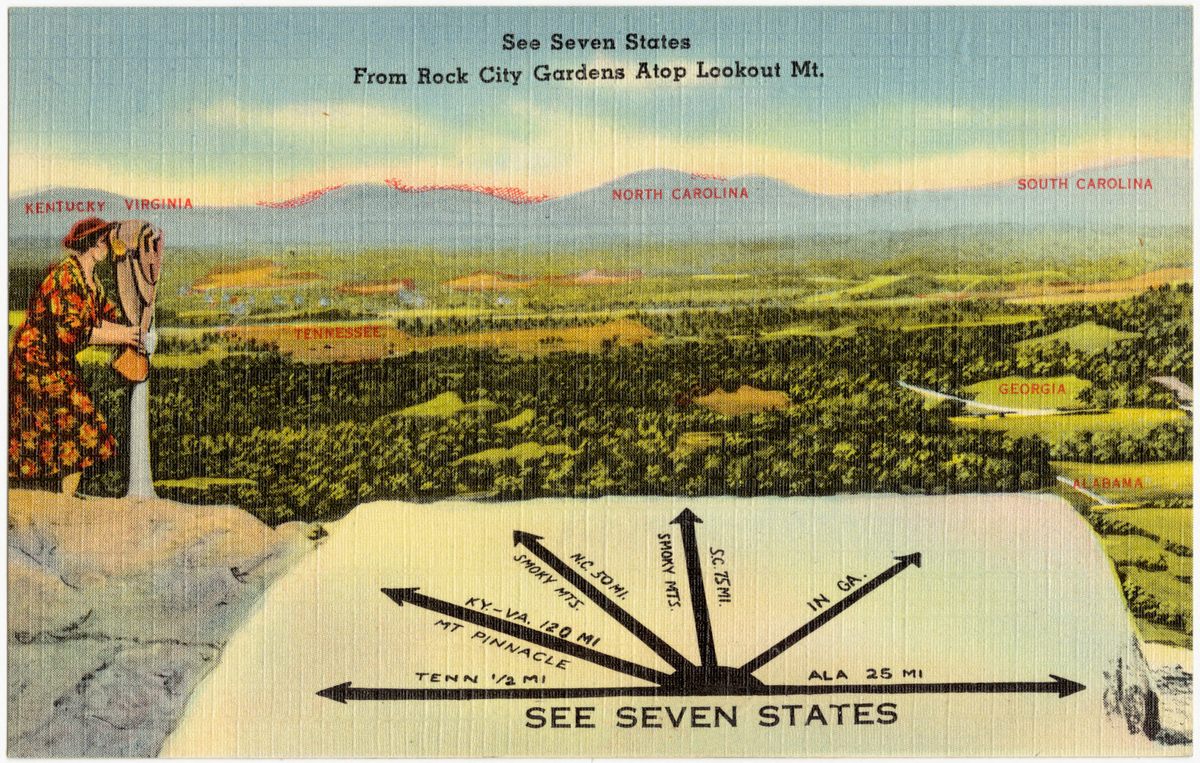

Rock City sits atop Lookout Mountain, along Tennessee’s border with Georgia, where on a clear day visitors can, as promised by some of its billboards, see seven states. It was founded by Garnet Carter, who moved to the mountain in 1894, and first planned to develop it into a neighborhood called Fairyland, after his wife Frieda’s love of German folklore and mythical creatures. While Garnet was working on bringing his vision for the 700-acre mountain site to life, Frieda developed a trail and gardens. Sensing that visitors might be interested in the scenery, the Carters changed their plans and opened Rock City Gardens to the public on May 21, 1932.

A 1920s effort to expand the road system in Tennessee had literally paved the way for attractions like Rock City. In 1922, the state maintained only 244 miles of state roads; by 1926, there was a 6,000-mile network crisscrossing the state. But the Great Depression had rocked the United States in 1929, especially the rural South, and travel was seen as a luxury. Carter needed to find a way to draw visitors to his mountain top.

To spread the word about Rock City, Carter hired Clark Byers, a sign painter who worked for a local advertising agency. Instead of constructing billboards, Rock City followed in the footsteps of Mail Pouch, a West Virginia tobacco company, which painted advertisements on existing barns. Byers was tasked with convincing farmers on rural backcountry roads to let him redecorate. Those who offered up their rooftops were compensated with free entry into Rock City, promotional items, or sometimes a rental fee of $3 to $5 a year.

The first Rock City barn, with its black background and white block letters, was near Kimball, Tennessee, about 30 miles west of Lookout Mountain, appeared in 1935 or 1936. Byers worked quickly, carefully crawling up ladders and painting freehand, and could complete up to three barns per day at $40 per barn. It wasn’t easy: there was the risk of falling from the roof, and over the course of his career, he was chased by dogs and even a longhorn steer. Soon, there were 900 barns in 19 states—from Michigan to Texas—announcing the wonders of Rock City.

As the country came out of the Great Depression and personal vehicles became more affordable, interstate travel rose, and Rock City saw visitor numbers skyrocket in the years following the barn ad campaign.

“The barns told people about it,” says Bill Chapin, former CEO of Rock City and a relative of the founders. But he believes that thanks to the “the experience that Uncle Garnet and Aunt Freida provided,” soon “their guests were the biggest promoters,”

The advertising advantage offered by the barns didn’t last for long. The creation of the Interstate Highway System in 1956 may have ushered in a golden age of American travel but it also made the two-lane rural roads, where the Rock City barns were, almost obsolete.

To make matters worse, the 1965 Highway Beautification Act placed restrictions on billboards like the Rock City barns, which the Johnson administration—or more specifically the First Lady—found to be eyesores. Many of the barns that were located in commercial zones had to be painted over. Byers did the work again, repeating his previous journeys.

Byers continued to maintain the Rock City barns until an accident forced him into retirement in 1969. He then opened his own roadside attraction, Sequoyah Caverns, which operated from 1965 to 2013 with its own painted barns.

These days, Rock City, which receives half a million visitors annually, doesn’t depend on painted barns for promotion. Over the decades, many of the original 900 billboards have disappeared, the barns painted over, demolished for road expansion, or even destroyed by tornadoes. One in Kentucky was disassembled and reassembled in the American Sign Museum. Rock City now advertises with traditional billboards and online ads—but about 70 of the original barns remain, most of them in Tennessee. “We’ve got relationships with barn owners that have been going since the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s,” says Chapin.

Roy Davis of R&R Outdoor now handles the barn painting. Sometimes he reaches out to landowners to offer to repaint their fading signs. Other times, they contact him, aware of their role in roadside Americana. “For us to come out and paint it, they’re excited for that. It helps preserve that and it helps preserve a part of their family history. We’ve got a wood barn up in Crossville [Tennessee] that the whole reason the husband and wife bought the farm was because it had a Rock City barn on it,” says Davis.

But it’s not always that simple. “If the barn falls down, they can rebuild the barn, but we cannot reprint or paint the top with a Rock City on it any longer, because it doesn’t meet the new standards,” says Davis of the regulations on roadside signage. “That’s why we lose a lot of them and are losing two, three a year, probably.” He’s also struggled to find sign painters with the necessary skills to maintain the murals.

Rock City is committed to continuing the legacy. A 2021 partnership with the Tennessee Titans football team led to the restoration of three original barns with a new design highlighting the brands, with Rock City’s website showcased. The company also keeps a map online marking the general locations of the barns. For the intrepid road tripper: some can be located using Google Maps and Instagram geo-tags, but you never really know if you’ll find one until you get there. It’s like searching for buried treasure.

The Rock City barns are a reminder of a different time that feels far removed from the seemingly endless stretch of similar highway billboards. They elicit a feeling of being piled into the car with your family, following the signage instead of staring at a screen.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook