A 16th-Century Book on Forest Laws Had Alarming Rules About Dogs

“Who may keepe dogges within a forrest?”

The year was 1598, and if you wanted to keep a dog in an English forest, you were going to have to obey some seriously complicated rules. In some places, certain men could keep greyhounds or mastiffs. In others, it was “little dogs” only. And if you wanted a spaniel? Well, you had better get a grant from the king, or risk serious legal consequences.

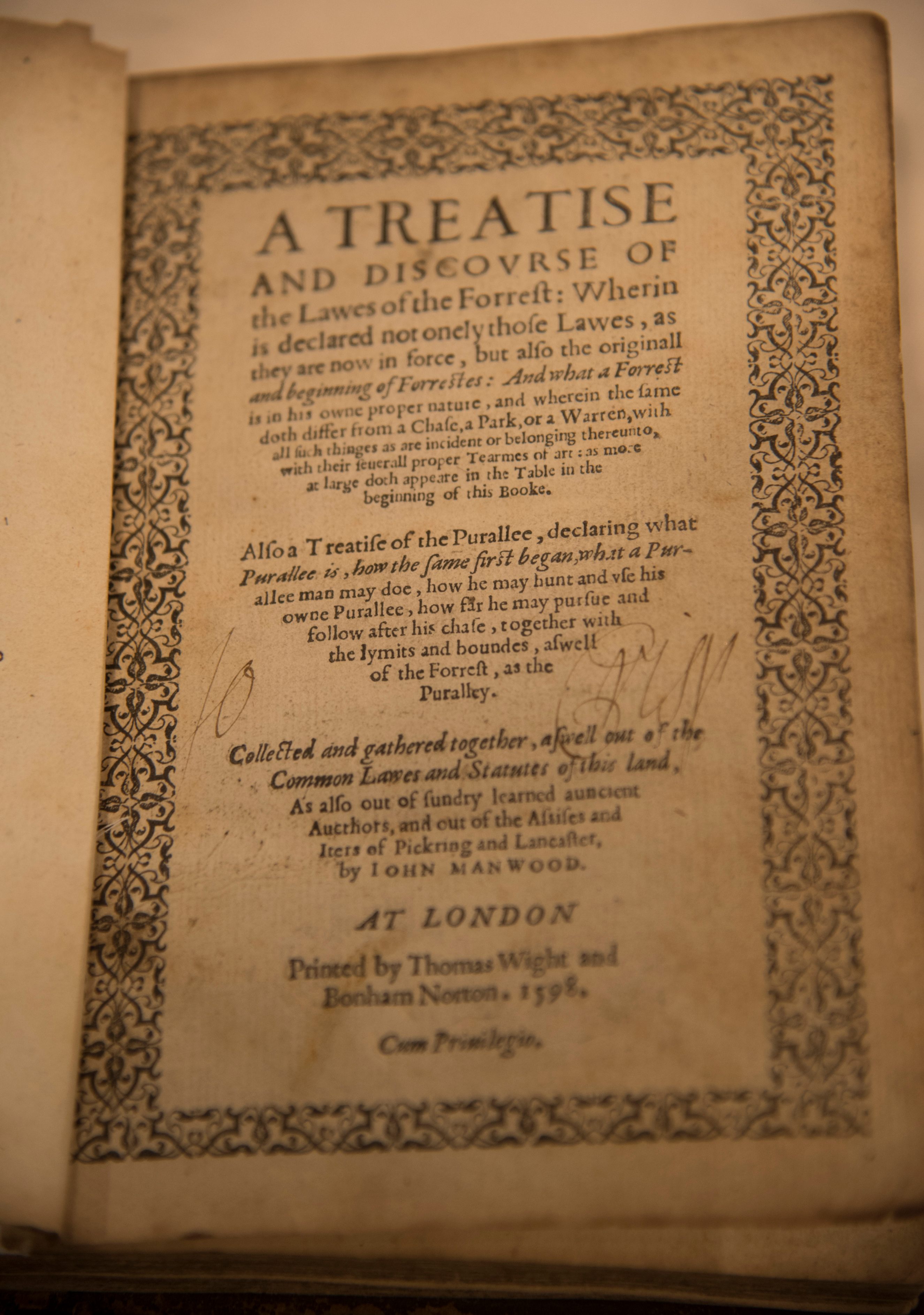

These, and other rules, are laid out in a treatise by John Manwood, a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn in London. Manwood was also a gamekeeper of Waltham Forest, and Justice in Eyre—a judge of a particular kind of court—of the New Forest under Queen Elizabeth I. The book was first published for private circulation in 1592, then publicly in 1598. For centuries, it was the go-to guide for forest law. This 1598 edition is the oldest book in the library of London’s Kennel Club—the self-professed “biggest dog library” in Europe. (To be clear, it’s the biggest library of books about dogs, rather than the biggest library where you can borrow dogs—or the library where you can borrow the biggest dogs.)

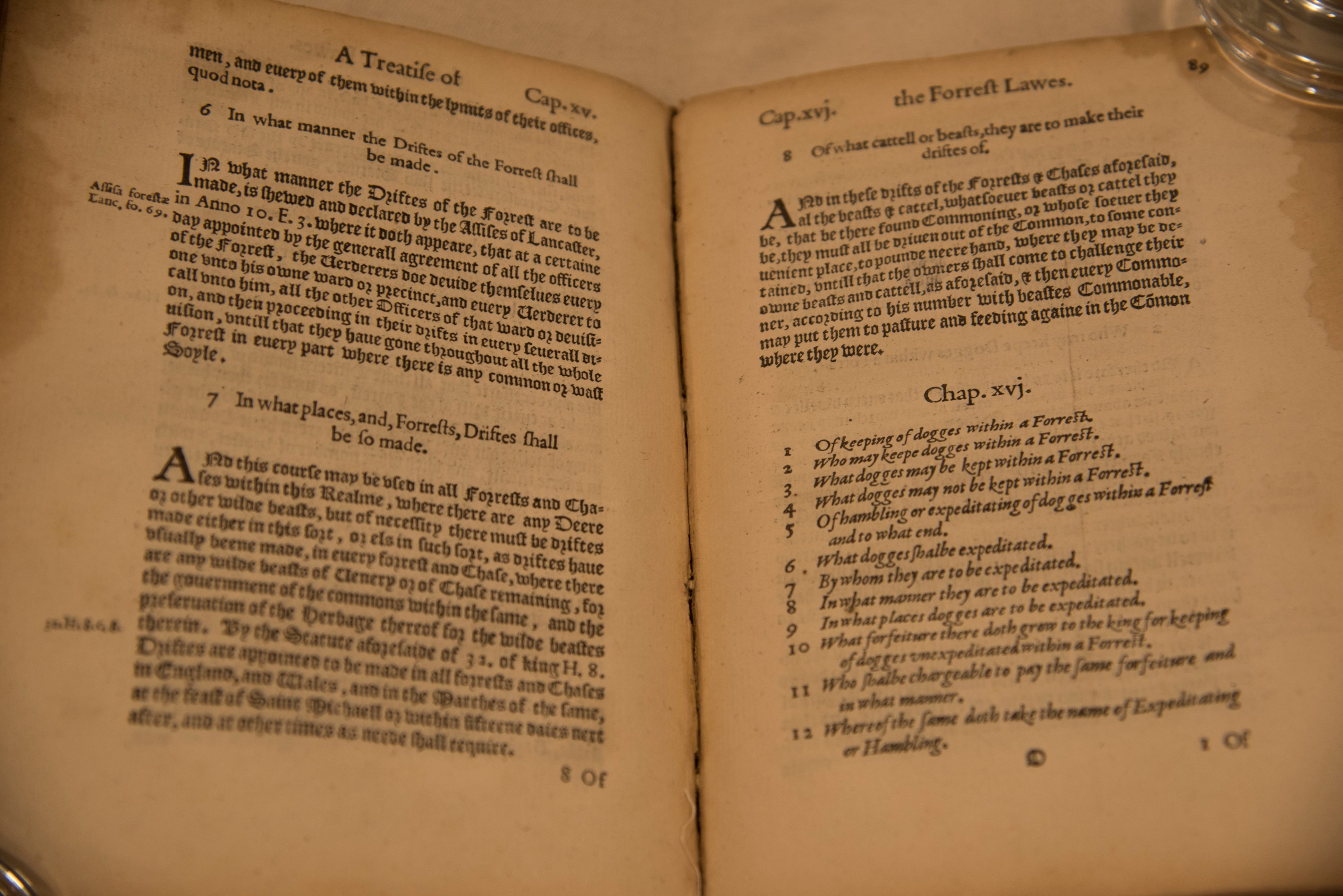

Lawes of the Forrest was simply the short form of the title. Its full 141-word title promised, among other things, to explain the legal difference between such woodland spots as a forest, a chase, a park and a warren. But in this rambling text, it is Chapter 16 that’s of the most interest to dog owners, whether contemporary or historical. In it, Manwood explains which dogges may, or may not, be kept within the forest, and under what conditions.

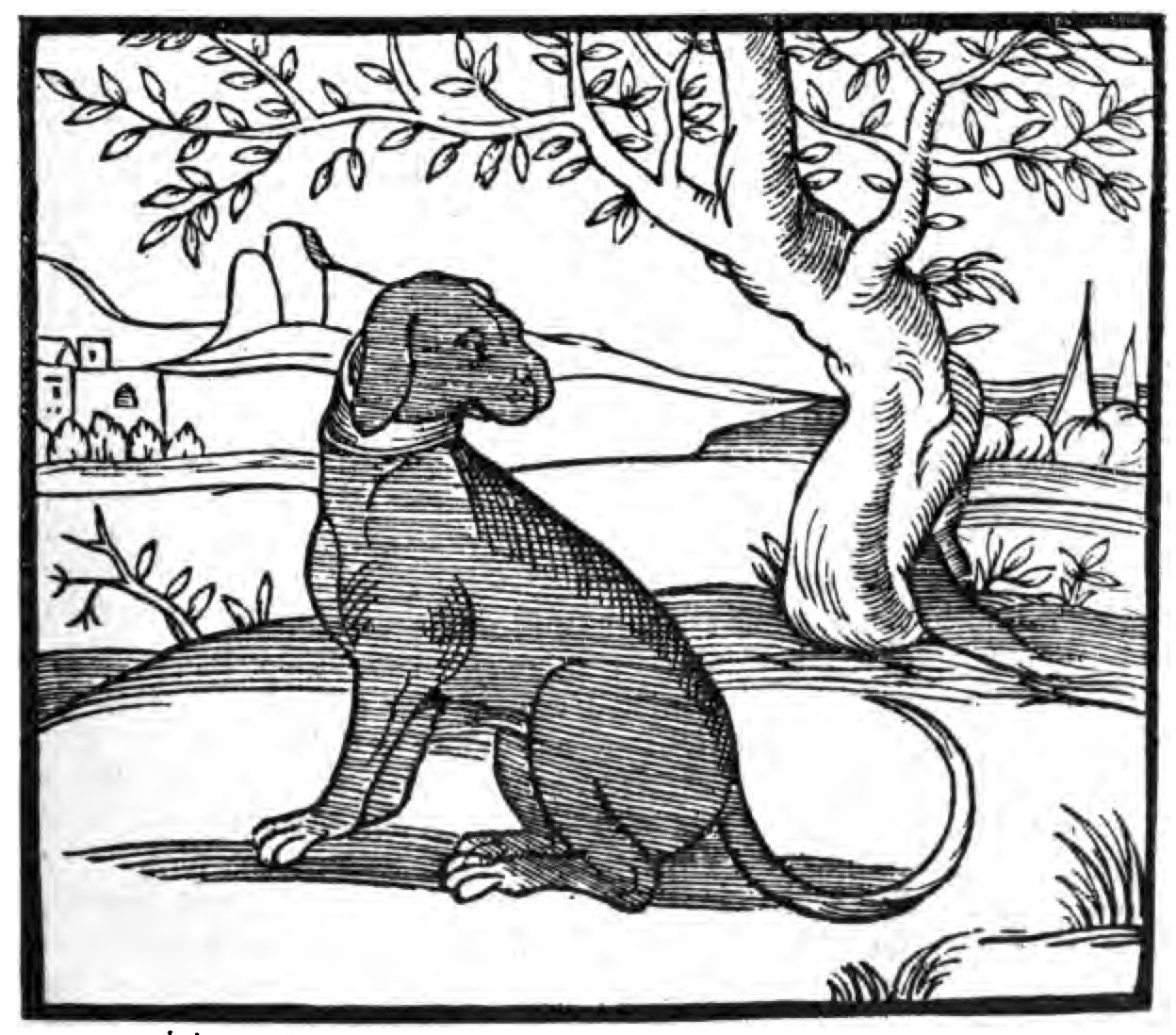

Many of these laws relate specifically to hunting, says Ciara Farrell, the Club’s library and collections manager. To own a dog used for hunting, people had to have special hunting licenses, issued by the king. “All other dogs must be expeditated or hambled,” she says, “which was a pretty nasty practice whereby dogs had some claws removed or had the pad of one foot damaged.” Simply muzzling them, the book decreed, was not sufficient. Generally, only mastiffs required hambling—though, Manwood acknowledged, “there is more Danger in [greyhounds] than in Mastiffs.”

Every third year, “the Regarders of the Forest” would visit these woodlands to check that dogs had been appropriately hambled. This maiming prevented them from being able to run at speed, or help surreptitious deer hunters on the prowl without a licence. The penalty wasn’t tremendous if you didn’t maim your dog—normally just a fine. But if your pet was found to have hurt or killed a “Wild Beast of the Forest,” the law might come crashing around your ears.

This was one of a number of books and treatises published at the time that explained how dogs needed to be kept. Manwood’s Lawes of the Forrest is a legal textbook—others have less authority, but are much bossier. In George Turbervile’s 1576 Booke of Hunting, he explains that hunting hounds should have their kennels in the eastern part of the house, and have their own courtyard. “The greater and larger that it is, the better it will be for the Houndes,” he wrote.

There were interior decor rules, too—the floorboards should be neatly laid, to minimize “spyders, flease” and other insects, and the walls “well whited.” Puppies, when they came, required a Pinterest-worthy bed, made of an open-topped barrel pushed on its side and filled with straw. “Set it by a place where there is ordinarily a good fyre,” Turbervile instructed. A loose netting over the entrance made sure “that other dogs do not byte them” and they weren’t trodden on. And feeding baskets, crucially, “should not be emptie at any time.” A far happier instruction than anything to do with expeditation.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook