Way Before Roller Coasters, Russians Zipped Down Enormous Ice Slides

These artificial mountains were fast, thrilling, and probably very dangerous.

Russia is flush with chilly, wind-whipped mountains. Running north-south in the country’s western half are the Urals—older than the dinosaurs and stippled with spruce, pines, and firs. Down near the southern border, just above Georgia, is Mount Elbrus, a volcanic peak rising 18,510 feet among the Caucasus Mountains, with snow on its summit and hot springs on its flanks. The far eastern side of the country has one range after another swooping across it.

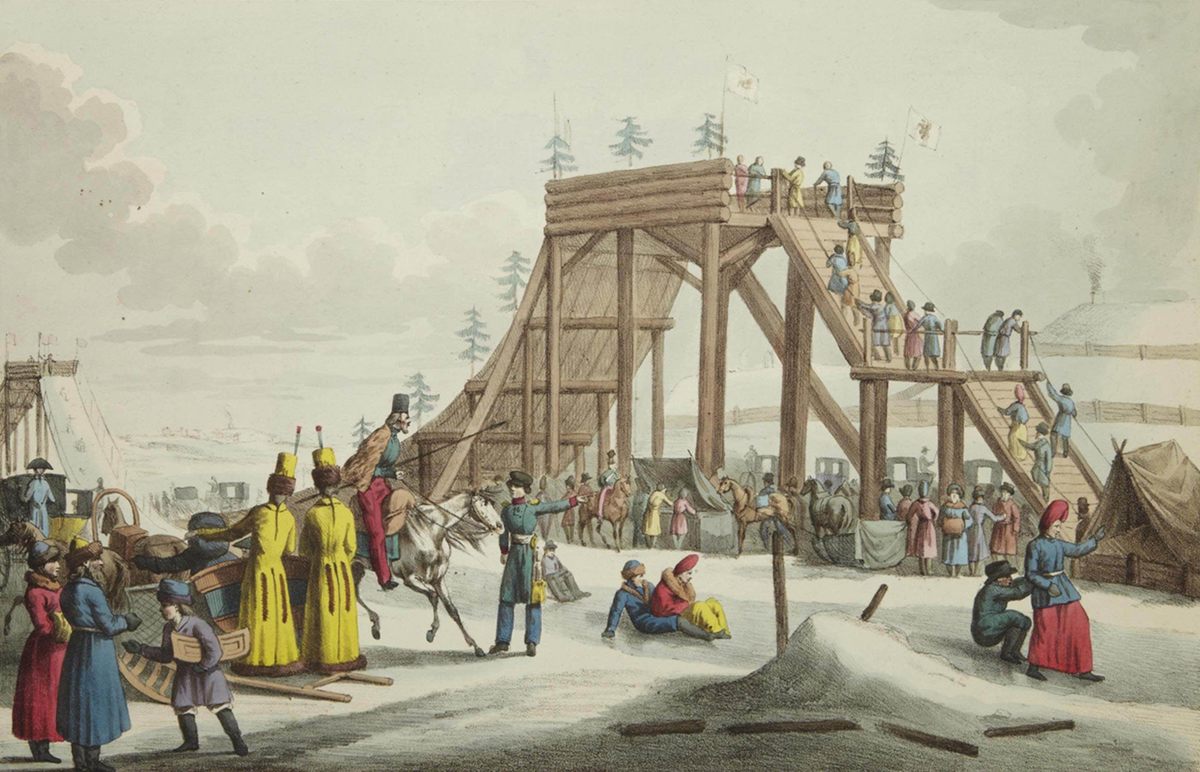

A few centuries ago, these icy peaks were temporarily joined by others—much smaller but ferocious in their own right. In public squares and private courtyards rose wooden structures sloped like hills. Once slicked with ice, they promised zippy, spectacularly dangerous fun.

From the 15th or 16th century onward, according to roller coaster enthusiast and historian Robert Cartmell, these “ice slides” or “flying mountains” went up in several Russian towns near rivers—St. Petersburg and its Neva River, in particular. These thrill rides were long, tall, and quick, and ultimately helped pave the way for today’s safer, but still scream-inducing amusements. “Most students of roller coasters believe the origin of the rides can be traced” to these water-slicked slopes, Cartmell wrote.

Intrepid riders clambered up a set of wooden stairs to as high as 70 or 80 feet in the air, according to Australian National University historian Carroll Pursell in the article “Fun Factories: Inventing American Amusement Parks,” published in the history-of-technology journal ICON. They settled into sleds—at first nothing more than a hollowed block of ice stuffed with a bit of straw and a single measly rope to fasten them in—and then plummeted down at a 50-degree angle. The slides were watered each day to keep them slick and smooth, and sand was heaped onto the track at the bottom to slow riders down.

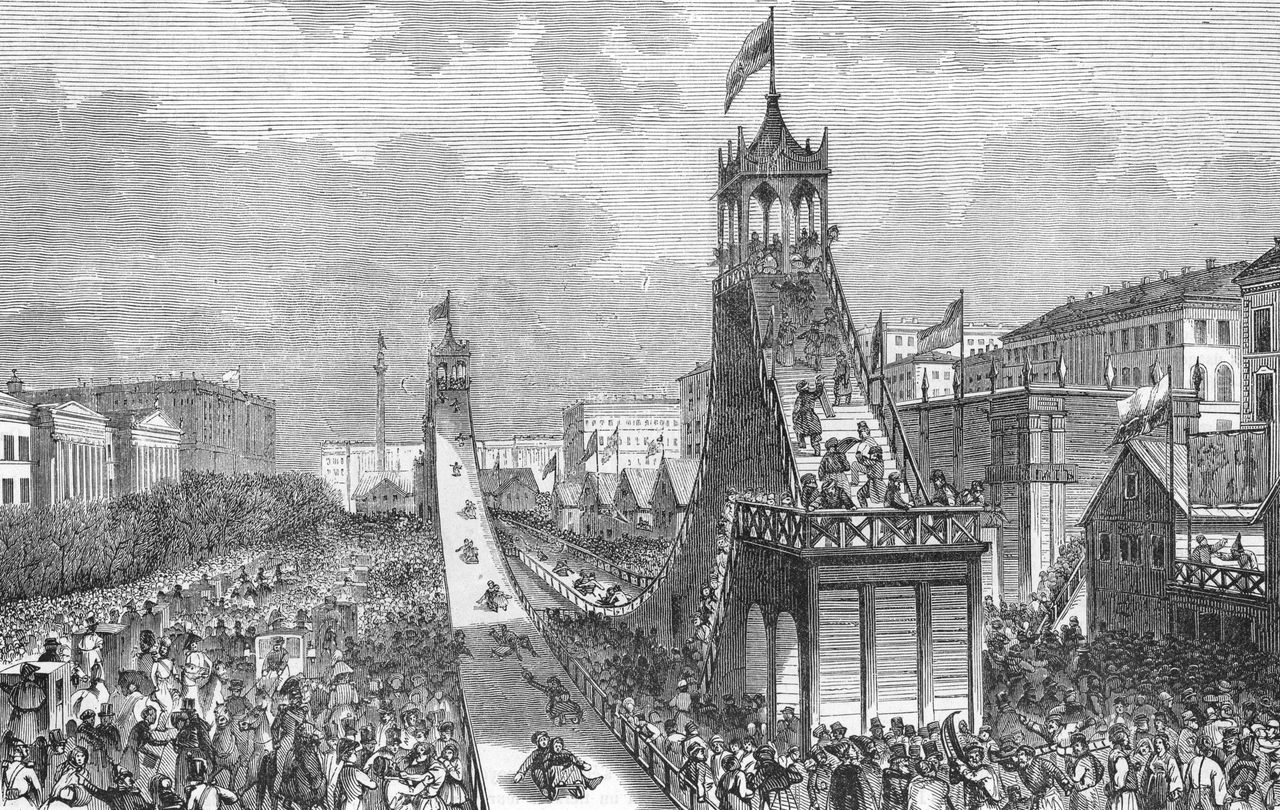

By the 1700s, these winter amusements soared above the shore of the Neva as part of public winter festivals. The slides sometimes spanned several blocks and were flanked by trees, cut and re-erected to evoke a forest grove. The artificial mountains were often topped by ornate pagodas or flapping flags, and surrounded by torches that allowed the thrills to continue after dark.

Aristocrats and other well-moneyed people mustered their courage, too. In The Incredible Scream Machine: A History of the Roller Coaster, Cartmell cites a dispatch from the court of Anna Ioannovna, empress from 1730 to 1740. The writer describes “a new diversion” that was “wide enough for a coach” and “had water flung upon it, which soon froze, and then more was flung, till it was covered with ice of a considerable thickness.” The “ladies and gentlemen of the court” plopped themselves on sledges and girded themselves for a flight to the bottom, “for the motion is so swift that nothing but ‘flying’ is a proper term.”

But to that observer, the prospect seemed more fearsome than fun: “Sometimes, if these sledges meet any resistance, the person in them tumbles head over heels; that, I suppose, is the joke.... I was terrified out of my wits for fear of being obliged to go down this shocking place, for I had not only the dread of breaking my neck, but of being exposed to indecency too frightful to think on without horror.”

The slicked mountains later caught the eye of Empress Elizabeth and then Catherine the Great, who is said to have slid down at least once, according to Virginia Commonwealth University historian George E. Munro, before commissioning a pair slides to amuse the courtiers at her Oranienbaum Palace on the Gulf of Finland. Cartmell writes that some Russian rulers even brought the mountains inside, sometimes swapping ice for soapy water. Tsarevich Alexei of the House of Romanov reportedly barreled down one atop a pillow instead of a sled.

One visitor to a winter festival in 1813, Scottish painter, author, and traveler Robert Ker Porter, described the experience in a manner relatable to any modern coaster aficionado. “The sensation excited in the person who descends in the sledge is at first extremely painful, but after a few times, passing through the cutting air, it is exquisitely pleasurable,” he wrote. “This seems strange, but it is so; as you shoot along a sort of ethereal intoxication takes hold of the senses, which is absolutely delightful.”

By the 19th century, when World’s Fairs had thrust midways and rides into the international spotlight, Pursell writes, the amusements had earned an appropriate moniker: “Russian Mountains.” In the 1880s, news of these frozen festivities had reached all the way to Minnesota, where the city of St. Paul built its own “Ice Palace,” featuring toboggan slides, an ice rink, and a curling tournament modeled after the Russian precursors.

Over time, these attractions gained wheels and tracks, and then traction among riders in France, where at least two coasters named after the Russian Mountains debuted in Paris and Belleville in the first quarter of the century. As the 19th century rolled into the 20th, coasters began to swoop across amusement parks all over the world, and found passionate fans in America, from New York to Orlando, and Long Beach to Cleveland, which now markets itself as a premier destination of the coaster world. (One ride at Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, whooshes at 120 miles per hour, no ice needed.)

Meanwhile, the Russian roots of winter thrill rides live on. You can still race down an ice slide at winter festivals in Moscow and elsewhere. And when a thrill-seeker who speaks French or Spanish wants to climb and then plunge, wind roughing her hair and a happy shriek escaping her throat, you might hear her mention a montagne russe or montaña rusa. They’re still the terms for “roller coaster.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook