The History and Mystery of Russia’s ‘Valley of Death’

A volcanic gorge in remote Kamchatka has given up some of its secrets—but not all of them.

The Kamchatka Peninsula, in Russia’s Far East, is a volcanic winter wonderland. Snow blankets a chain of eruptive mountains here that shower the land with molten fireworks. It is as beautiful as it is biodiverse, with a myriad of aquatic, aerial, and terrestrial species.

But there’s lethal trouble in this chilly paradise. In one of its smaller valleys, animals wander in but not out.

When the snow melts, various critters, from hares to birds, appear in search of food and water. Many die soon thereafter. Predatory scavengers such as wolverines spot an easy dinner; they slink or swoop into the valley—only to die themselves. From lynxes to foxes, eagles to bears, this 1.2-mile-long trough has claimed innumerable victims.

But the killer here is a phantom. The dead, whose corpses are naturally refrigerated and preserved, show no traces of external injuries or diseases that would be responsible for their expirations.

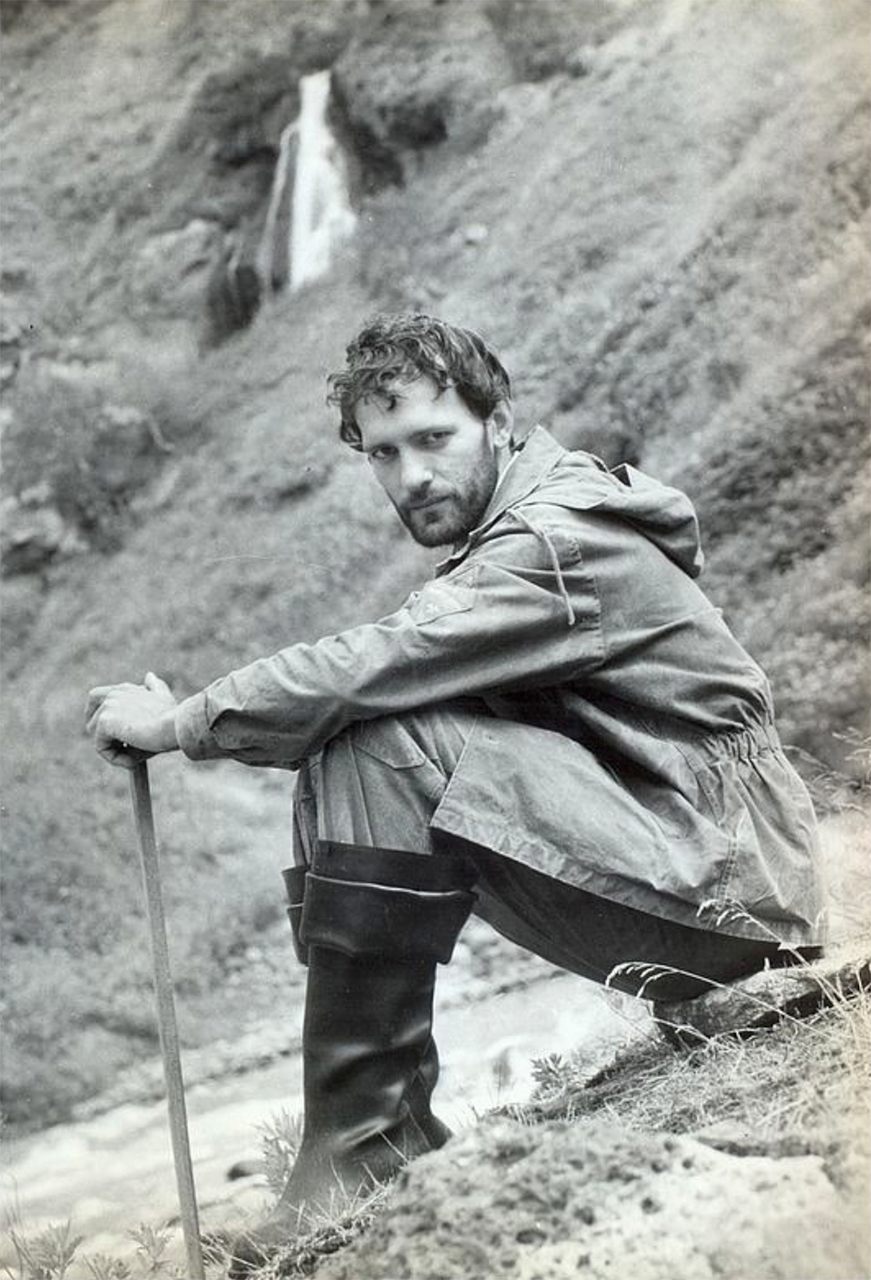

Vladimir Leonov, a volcanologist at Russia’s Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (IVS) who’s recognized by his colleagues as the site’s discoverer, identified the cause of death when he first came across the site, in 1975: It’s the result of a volcanic phenomenon—a common gas that nearly everyone is familiar with.

But while the forensic science has long been clear, unconfirmed stories about the place still abound. Some claim, for instance, that animal corpses are regularly removed from the valley—though no one can say by whom. Another mystery dates back to the mid-1970s. Viktor Deryagin, a student of Leonov’s who helped his instructor discover the valley, says that Soviet military officials, alerted to the valley’s existence, arrived in a helicopter, took some strange samples, and quickly departed. What did they gather and conclude?

Welcome to the Valley of Death, a site that remains as darkly enchanting—and as lethal—as it was when it was discovered 44 years ago.

Fewer than 350,000 people live on the Kamchatka Peninsula. Large portions of the region lack roads. If they existed, you could drive for an entire day and still be walled in by volcanoes. Many of the volcanoes here, like Tolbachik and Sheveluch, are hyperactive, and frequently limn the land in fresh coats of lava paint. Most of Kamchatka is an icy volcanic wilderness—a UNESCO World Heritage Site whose geological curiosities and extraordinary aesthetics compel scientific visitors from around the world.

Janine Krippner, a volcanologist at the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program, recalls lying on a cooled Kamchatkan lava flow, hearing nothing but the small bursts of volcanic gas sneaking out of the ground as birds flew overhead. During her most recent visit, she stood near a freshly chilled lava flow that was still 176° Fahrenheit—hot enough to toast her necklace from several feet away.

“There’s just no place like it,” she says.

With persistence and permission, many places on the peninsula can be accessed. That includes the Kronotsky State Natural Biosphere Reserve, which contains the relatively youthful (4,800 years old) Kikhpinych volcano. At its feet is the lichen-covered Valley of Geysers, whose bubbling pits shoot pillars of steam hundreds of feet into the azure sky. Discovered in 1941 by geologist Tatyana Ustinova and a scientific observer named Anisifor Krupenin, it remains a site of scientific intrigue that is also open to tourists.

But the Valley of Death—a comparatively quiet and diminutive crevasse, littered with the frozen remains of animals and located near an upper sliver of the Geyzernaya river within the reserve—is one place that is strictly off-limits.

Leonov died in 2016, at age 66, but his son, Andrey Leonov—a researcher at the S.I. Vavilov Institute for the History of Science and Technology—is well versed in his father’s adventures. So is his father’s one-time student Deryagin. Deryagin left academia long ago, worked in construction, and is now retired. After Andrey tracked him down on Russian social media, Deryagin recounted previously untold details about his scientific adventure with Leonov four decades ago. Together, both men tell an extraordinary tale of the site’s discovery.

Vladimir Leonov and Deryagin first visited and documented the valley on July 27, 1975. (There is, however, some dispute on the matter. Officials at the reserve acknowledge Leonov’s role in the discovery, but suggest that it was independently found by a man named Vladimir Kalyaev, the chief ranger at the time. Andrey Leonov insists that his father—a modest man more interested in scientific discovery than quibbles about credit—reached the valley, with Deryagin, four days before Kalyaev arrived.)

Prior to that date, a number of people—from employees of the reserve to scientists to tourists—had passed along a trail just 1,000 feet from the ravine. Some had seen collections of dead critters in the valley from time to time, but made no special note of it.

The animal deaths in 1975, though, were hard to ignore: Heavy snowfall had created pits over curious holes in the ground, and a plethora of animals—including five dead bears in one small area—appeared to have died in or around them.

Deryagin says that in Soviet times, geologists were instructed to immediately inform authorities about the mass death of people or animals, using a special radio channel. On July 27, Leonov did just that: He walked to the nearby Valley of Geysers, found a radio box, and called in his report.

The next day, Deryagin says, a military helicopter turned up, carrying a major, two young women (likely laboratory assistants), and a man (perhaps a biologist) who took copious notes . They performed a hasty autopsy on the dead bears, took samples of their flesh and teeth, then flew away.

Leonov and Deryagin performed their own scientific analyses, gathering as much data on the strange location as they could. Writing in the Kamchatskaya Pravda newspaper in the spring of 1976, Leonov described the discovery, coining the term “Valley of Death”—an homage to several lethal valleys around the world, including a volcanic gorge in Arizona and parts of certain volcanic folds in Indonesia. In this segment of Kamchatka, Leonov wrote, borrowing a passage from another writer, “nature seems to have pronounced its curse.” All life is snuffed out in a place that “breathes extermination and devastation.”

Other researchers quickly corroborated his findings. A 1983 paper—whose primary author, Gennady Karpov, is now the deputy director for science at the IVS—says that over a five-year period, rangers from the reserve found the corpses of 13 bears, three wolverines, nine foxes, 86 mice, 19 ravens, more than 40 small birds, a hare, and an eagle.

Like Leonov and Deryagin, a well-known bear researcher named Vitaly Nikolayenko visited the valley in 1975. Before one of the peninsula’s brown bears mauled him to death, in 2003, he published a book that chronicled his scientific work, including the research he’d performed in the valley. Notably, he wrote, many bears here seemed to have been in good health before they died. But the footsteps of one large male indicated that it had been very disoriented before it fell over and suddenly expired.

During one of his visits, Nikolayenko describes experiencing painful cramps in his lungs and acute dizziness, which resolved only after he’d clambered atop a windswept crest. Other visitors have reported similarly woozy sensations here, and accounts by reserve officials note headaches and weakness. (Reports of human deaths here remain unconfirmed, though some suggest that people have perished in the valley.)

Nikolayenko also recorded the deaths of 20 foxes, dozens of ravens, and 100 white partridges. The hares and adult birds, he wrote, seemed to have died in springtime and early summer, when the valley’s grasslands were freshly thawed.

Volcanologists and zoologists concluded that the animals that died in the valley usually died quickly, and only on the ground. Their hearts often lacked blood, but their lungs were engorged with it.

They’d suffocated, in other words. And any humans who lingered too long in the Valley of Death—a landscape filled with invisible volcanic gases, either toxic or asphyxiating—probably would too.

(Leonov had surmised that volcanic gases were the killers back in 1976. In the Kamchatskaya Pravda article, he astutely compared the deaths to those seen in volcanic realms elsewhere in the world, including Italy’s “burning fields,” where fumaroles—jets of hot volcanic gas—can create deadly mixtures. Those death pits that caught Leonov and Deryagin’s eyes in 1975? The heavy snowfall had probably walled in and concentrated the life-stealing gases escaping from those fumaroles, leading to denser die-offs.)

A range of gases are potentially present in the valley at any time, including sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide—pungent effusions that can damage respiratory systems. Some doses can be lethal, but a human would need to be exposed to a high quantity of them for a long time, says Helen Robinson, a researcher of geothermal systems at the University of Glasgow.

It’s far more likely that the speedy animal deaths in Kamchatka are due to carbon dioxide, a common volcanic gas that is both invisible and odorless. If there is enough of it, Robinson says, death can occur in a matter of minutes. (A grim example of this occurred in 1986 at Lake Nyos in Cameroon, where an uprush of carbon dioxide from the volcanic lake killed 1,746 people and 3,500 livestock overnight.)

Yuri Taran, a volcanologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico who has studied the Kamchatka region, says that specific outflows of the valley’s gases have not been officially reported. But given that the distinctly eggy smell of hydrogen sulfide is largely absent, carbon dioxide seems the likely culprit.

To Alexey Kiryukhin, a volcanologist at the IVS, the science is actually pretty simple. Carbon dioxide is denser than air; when it emerges from the ground, it pools in the valley’s dips. Small animals, attracted by the available vegetation in the warmer months, breathe it in and asphyxiate. So do the scavengers they attract.

But what happens to all those dead animals? According to a few tourism sites, scientists and volunteers regularly take away the corpses in order to spare rare animals higher up on the food chain from a grisly fate.

It’s a persistent rumor, but as yet unproven. Andrey Leonov notes that there’s no permanent human presence in the Valley of Death; the nearest one is in the Valley of Geysers, several miles away and across elevated terrain. People work in the reserve, he says, but “I hardly believe that they regularly clean the valley from corpses.”

Olga Girina, a volcanologist at the IVS, agrees. Though the lethal valley is within the reserve’s jurisdiction, she says, staff are not allowed to interfere in nature’s processes in any way.

Kiryukhin suspects that the death-defying tales of corpse retrieval are stories shared by tourism agencies to appease visitors concerned about the plight of the animals. (The reserve itself didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

When Leonov discovered the valley, he began his 1976 piece with the words of another scribe, writing that “everyone who comes here is horrified and fearful.” But he hoped that scientific rigor and reason would ultimately prevail, and provide a rational explanation for the animal deaths.

In 2015, a year before he died, Leonov contributed to a special scientific publication by the reserve that recounted the discovery. He urged his fellow scientists to conduct further research and continue to unveil the geological secrets of this “daughter of Kamchatka.”

His wish is likely to be granted. The Valley of Death may be dangerous and remote, but with such powerfully morbid gravity, it’s likely to draw more scientific prospectors in the years to come.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook