The Scrapbooking Lawman Who Documented 19th-Century Colorado

Sam Howe filled his books with newspaper clippings about crime in Denver.

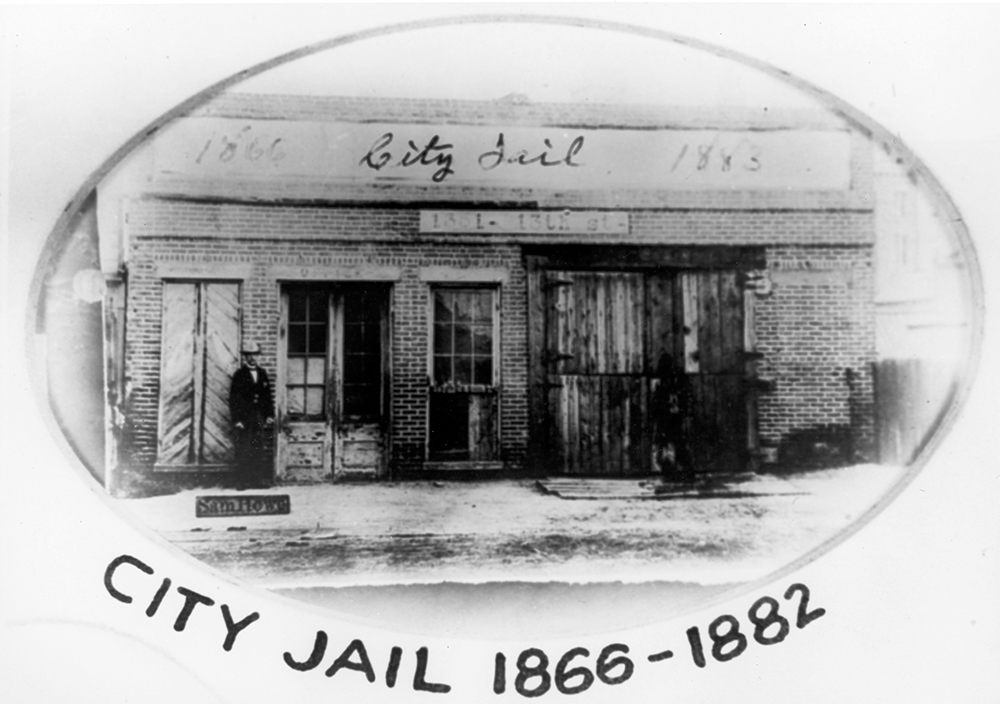

At the turn of the 19th century, Denver, Colorado, was a burgeoning town that had slowly morphed from a small mining camp into a bustling settlement. As the population grew, so did the need for policing. One lawman recognized that while there was law, there wasn’t much order, because there was no formal way of tracking misconduct.

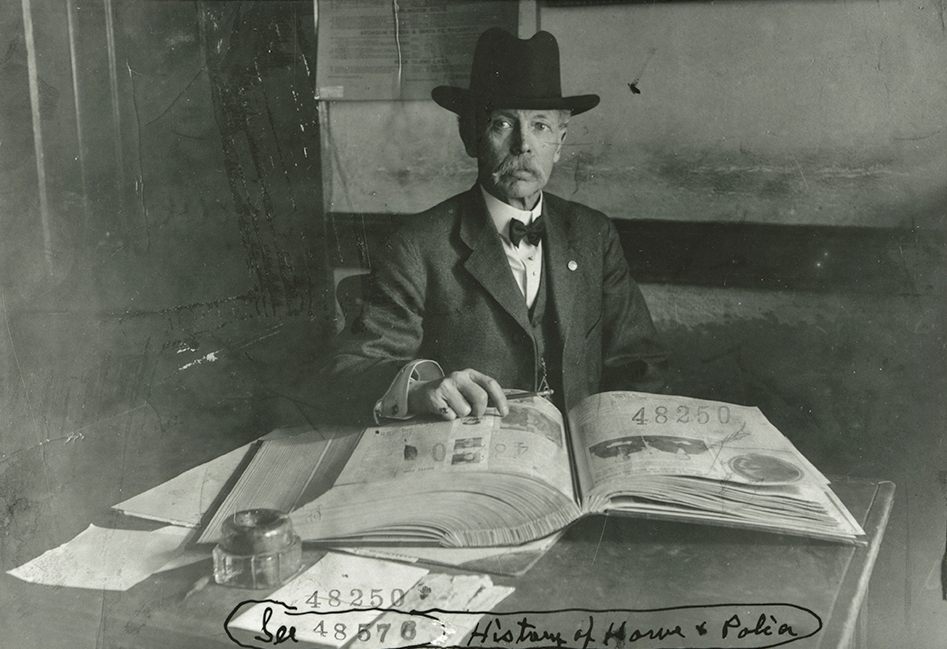

Dissatisfied with this disorganization, Detective Sam Howe developed a solution. He began creating scrapbooks filled with news clippings from the local papers, tracking the crime, criminals, and newsworthy happenings of the early days of Denver.

When Howe, born Simeon H. Hunt, moved to Denver, Colorado, after serving as a Union soldier in the Civil War, he became one of Denver’s first police officers. “He was a mysterious, quiet, shy, almost reclusive little man,” explains Clark Secrest, author of Hell’s Belles: Prostitution, Vice, and Crime in Early Denver. “But he put in many years on the police department, and he was well regarded in the community.”

During the early years of the police force, officers kept handwritten journals, but there wasn’t a collective place for everyone to share information. Howe wanted to develop a way to keep track of the people he had apprehended and connect them with other transgressions they had committed throughout the years, so he began meticulously hunting for connections and documenting them in scrapbooks. He got the idea from the newspapermen of the time, many of whom he had developed strong relationships with. He noticed that they kept track of their stories by clipping related articles in case they needed to do a follow-up. He decided to give it a try.

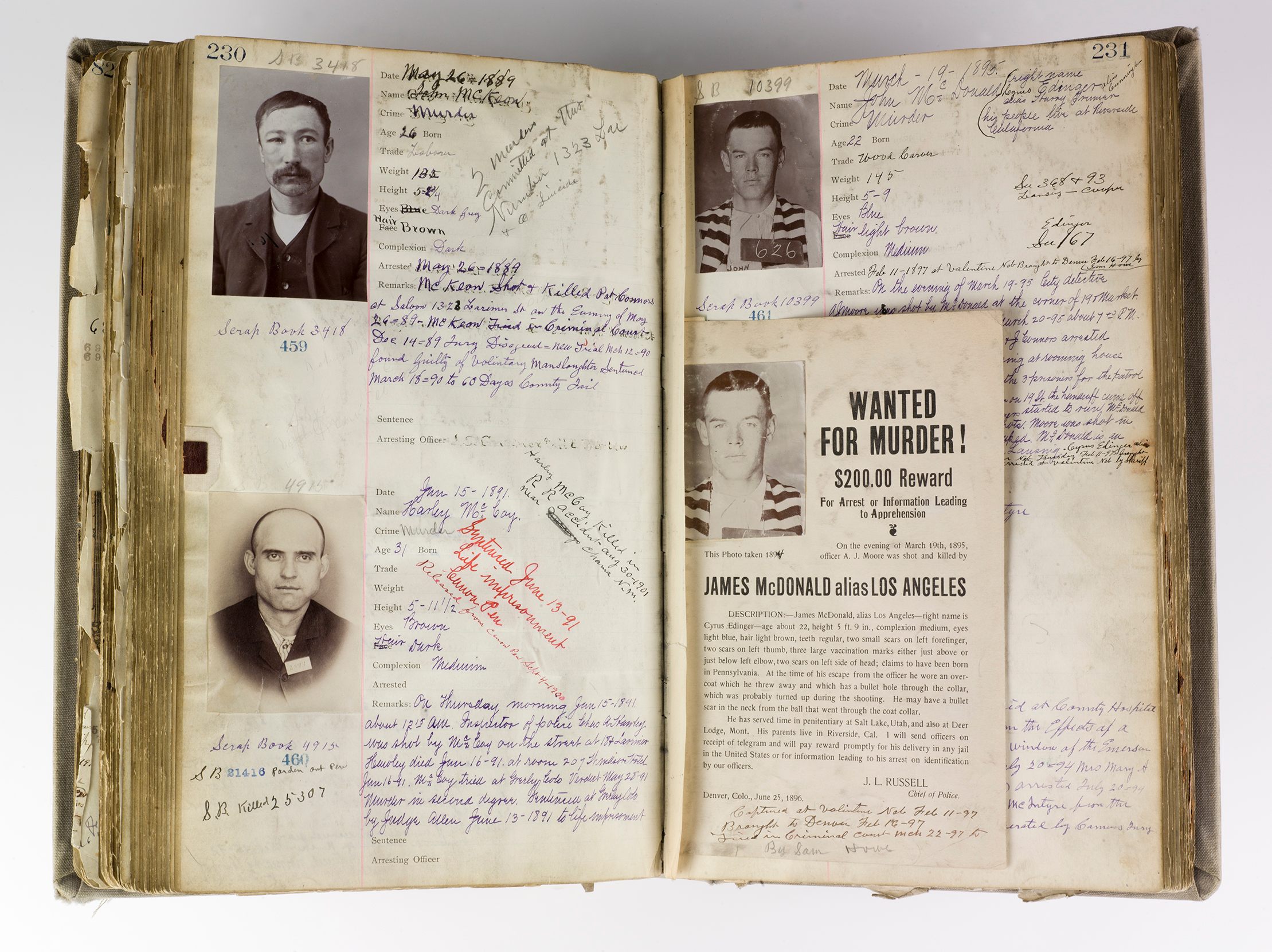

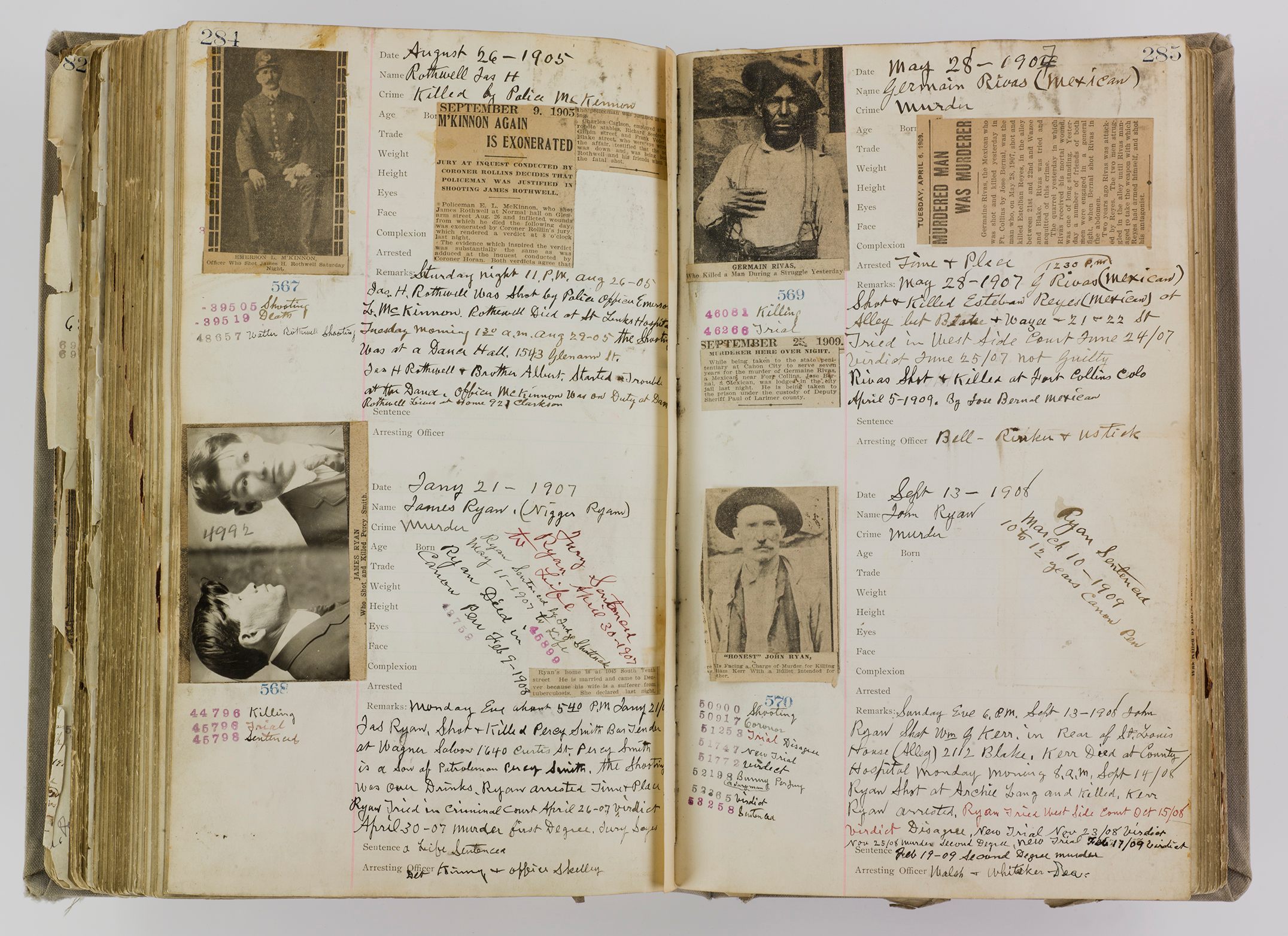

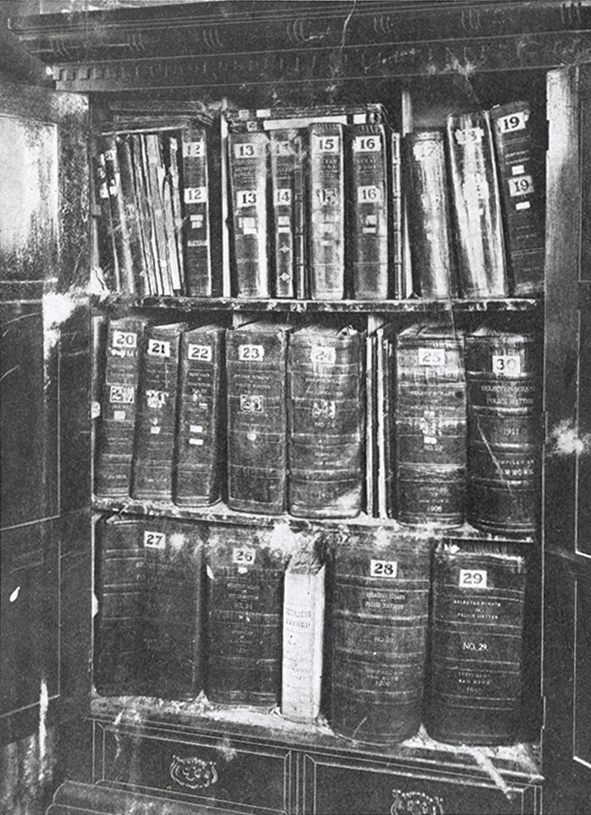

From 1873 until 1921, Howe clipped almost every single crime-related news story from the local papers and filed them in either his general crime record books or his murder books. His more general books were filled with Tetris-style clippings of news stories in chronological order. Records in his murder books included descriptions of crimes, physical descriptions of criminals, case remarks, photographs, and newspaper clippings.

The general crime books offer a glimpse into the norms of life in early Denver. Headlines were often colorful and leaned into the drama of the crimes and other tragic incidents. The types of stories Howe saved ranged from accidents (“Message of Death for Happy Wife: Mrs. Henry J. Earthman Returns Home from Matinee to Learn Her Husband’s Mangled Remains Were in Morgue”) to suicides (“Mrs. Pearl Honegger, Young and Beautiful, Was Weary of Living and Swallowed Acid”) to assaults (“Striking a Woman Proves Expensive”). He also included stories about burglary, forgery and fraudulent checks, embezzlement, indecent exposure, disturbing the peace, drunkenness, poisonings, and more.

Howe’s murder books, unsurprisingly, feature stories that are exclusively about murder. They were often only added after a resolution had been met, serving as a complete, simplified record of the case.

The crimes and incidents in Howe’s books were each given a number. A connected story would be given another number associated with the original, allowing people to track developments from arrest to imprisonment to parole. Murders and major crimes were indexed by the names of the offenders so that readers, who were primarily law enforcement officers and reporters, could quickly and easily find out about prior offenses instead of having to sort through an unorganized mass of information.

During his research for Hell’s Belles, Secrest uncovered stories about officers in other cities relying on Howe’s books to help them find information about people from their areas. In 1903, the Chicago police department asked for help locating a missing man they believed had relocated to Colorado. Within 30 minutes, Howe’s books revealed that the man had drowned in nearby Pueblo, Colorado.

Not only did other officers use Howe’s books for background research or information, but so did the very newspapers that he clipped stories from. Howe was beloved by reporters and always gave them free and open access to study and borrow his books.

Howe only actively worked on the streets until 1883. After that time, he became a detective and eventually became chief of detectives twice—he was demoted once after an act of insubordination—during his 47-year-career.

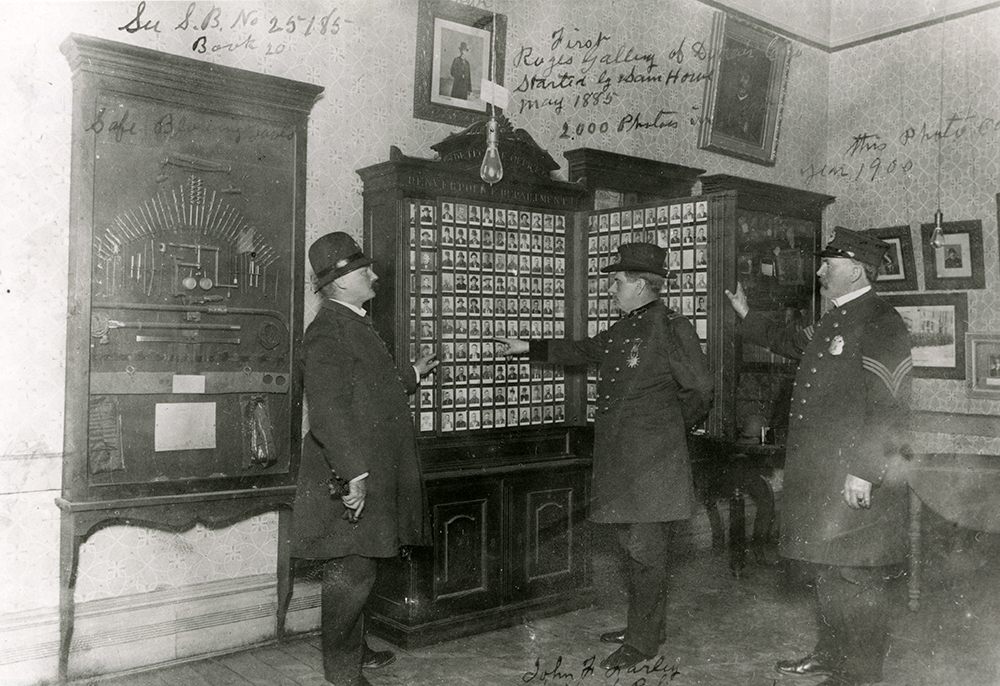

In addition to his books, Howe also started Denver’s first “rogues gallery,” which was a collection of mugshots and physical descriptions that helped police with suspect identification. Howe’s gallery eventually grew to contain the photos of around 2,000 criminals. He also ran a museum filled with crime paraphernalia that showcased items including safecracking equipment, knives, guns, and a rope used to hang criminals sentenced to death. Officers traveled from all around the country to see Howe’s museum and to use his books for inspiration for starting criminal databases back in their own cities.

Howe stayed on the force until he retired on February 1, 1921, at age 81. He stopped scrapbooking when he retired, but according to the nonprofit organization History Colorado, members of the police department continued creating and cross-referencing the ledgers until 1934.

On April 4, 1930, Howe died at age 90. Nine years later, a century after his birth, his scrapbooks were donated to History Colorado. In total, the Sam Howe collection at the History Colorado Center in Denver contains 44 massive article ledgers (some nearly a foot in width), 25 indexes, and two murder case ledgers. It contains over 100,000 clippings.

The weathered and delicate condition of the books now requires them to be kept in a special temperature- and humidity-regulated room at the History Colorado Center. However, a few of the scrapbooks (both general and murder books) were put onto microfiche and are available to the public for easy viewing.

Secrest notes that in 1895, the Chicago Times described Detective Howe’s scrapbooks as “the most valuable as well as the most complete record of a city’s crime and criminals outside the department libraries of Chicago and New York.” Howe’s ideas to track everything in one place, collecting mugshots for easy identification, and setting up a museum for the education of other officers, led him to be considered one of the leading crime statisticians in the nation.

Eventually, Howe’s method became outdated, but his recognition of the need for a tracking system in Denver at a time when no other officers in the region were attempting to do that shows foresight. While larger cities such as Chicago and New York did have tracking in place, smaller locales including Denver did not. Howe’s innovative ideas served as inspiration for those officers who traveled to Denver to learn about his methods before utilizing them in their districts.

Howe might have faded into the past, his documentation of early Denver lives on in the archives of History Colorado.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook