How the English Failed to Stamp Out the Scots Language

Against all odds, 28 percent of Scottish people still use it.

Over the past few decades, as efforts to save endangered languages have become governmental policy in the Netherlands (Frisian), Slovakia (Rusyn) and New Zealand (Maori), among many others, Scotland is in an unusual situation. A language known as Scottish Gaelic has become the figurehead for minority languages in Scotland. This is sensible; it is a very old and very distinctive language (it has three distinct r sounds!), and in 2011 the national census determined that fewer than 60,000 people speak it, making it a worthy target for preservation.

But there is another minority language in Scotland, one that is commonly dismissed. It’s called Scots, and it’s sometimes referred to as a joke, a weirdly spelled and -accented local variety of English. Is it a language or a dialect? “The BBC has a lot of lazy people who don’t read the books or keep up with Scottish culture and keep asking me that stupid question,” says Billy Kay, a language activist and author of Scots: The Mither Tongue. Kay says these days he simply refuses to even answer whether Scots is a language or a dialect.

What Scots really is is a fascinating centuries-old Germanic language that happens to be one of the most widely spoken minority native languages, by national percentage of speakers, in the world. You may not have heard of it, but the story of Scots is a story of linguistic imperialism done most effectively, a method of stamping out a country’s independence, and also, unexpectedly, an optimistic story of survival. Scots has faced every pressure a language can face, and yet it’s not only still here—it’s growing.

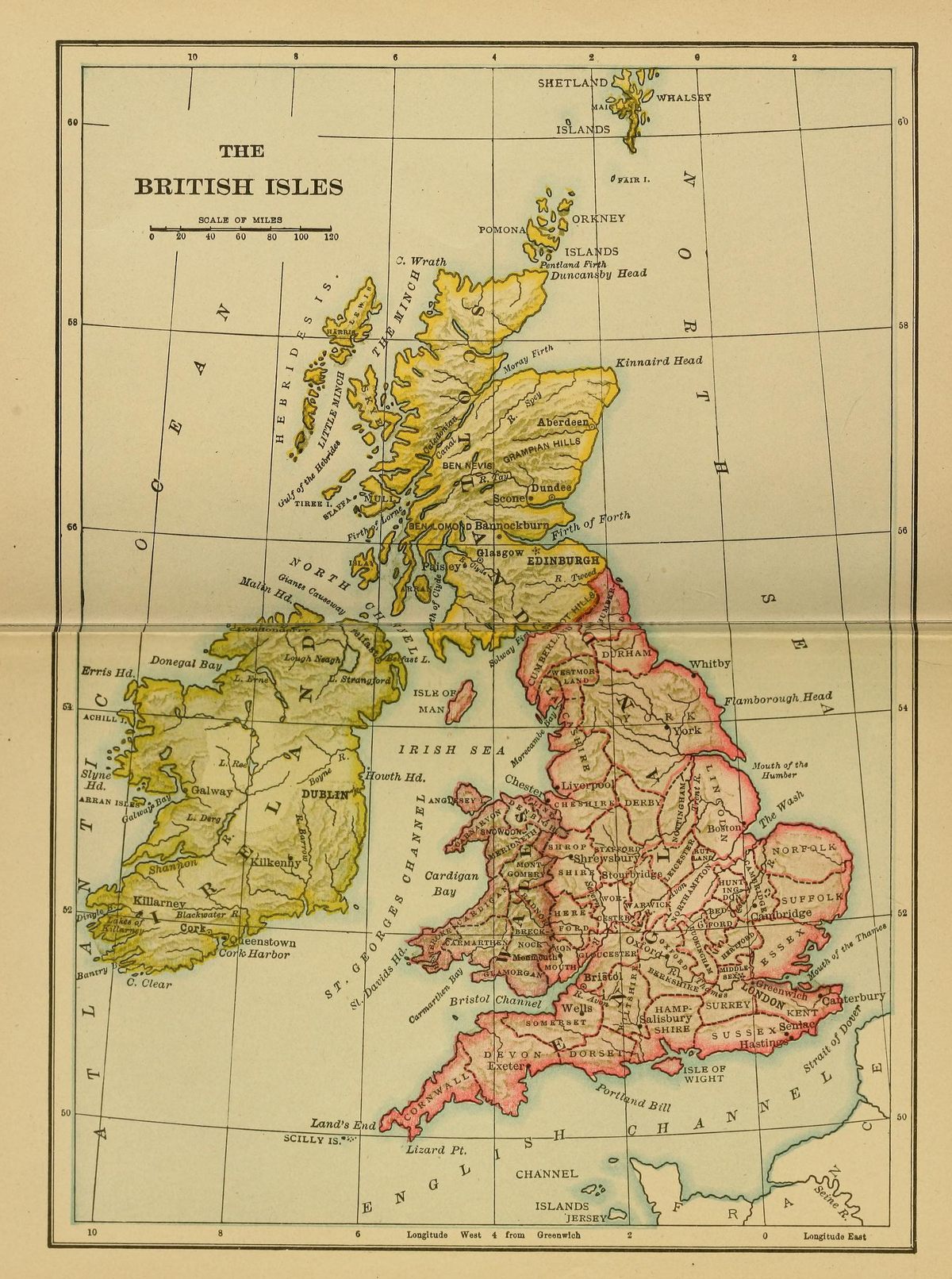

Scots arrived in what is now Scotland sometime around the sixth century. Before then, Scotland wasn’t called Scotland, and wasn’t unified in any real way, least of all linguistically. It was less a kingdom than an area encompassing several different kingdoms, each of which would have thought itself sovereign—the Picts, the Gaels, the Britons, even some Norsemen. In the northern reaches, including the island chains of the Orkneys and the Shetlands, a version of Norwegian was spoken. In the west, it was a Gaelic language, related to Irish Gaelic. In the southwest, the people spoke a Brythonic language, in the same family as Welsh. The northeasterners spoke Pictish, which is one of the great mysterious extinct languages of Europe; nobody really knows anything about what it was.

The Anglian people, who were Germanic, started moving northward through England from the end of the Roman Empire’s influence in England in the fourth century. By the sixth, they started moving up through the northern reaches of England and into the southern parts of Scotland. Scotland and England always had a pretty firm border, with some forbidding hills and land separating the two parts of the island. But the Anglians came through, and as they had in England, began to spread a version of their own Germanic language throughout southern Scotland.

There was no differentiation between the language spoken in Scotland and England at the time; the Scots called their language “Inglis” for almost a thousand years. But the first major break between what is now Scots and what is now English came with the Norman Conquest in the mid-11th century, when the Norman French invaded England. If you talk to anyone about the history of the English language, they’ll point to the Norman Conquest as a huge turning point; people from England have sometimes described this to me, in true English fashion, as the time when the French screwed everything up.

Norman French began to change English in England, altering spellings and pronunciations and tenses. But the Normans never bothered to cross the border and formally invade Scotland, so Scots never incorporated all that Norman stuff. It would have been a pretty tough trip over land, and the Normans may not have viewed Scotland as a valuable enough prize. Scotland was always poorer than England, which had a robust taxation system and thus an awful lot of money for the taking.

“When the languages started to diverge, Scots preserved a lot of old English sounds and words that died out in standard English,” says Kay. Scots is, in a lot of ways, a preserved pre-Conquest Germanic language. Guttural sounds in words like fecht (“fight”) and necht (“night”) remained in Scots, but not in English.

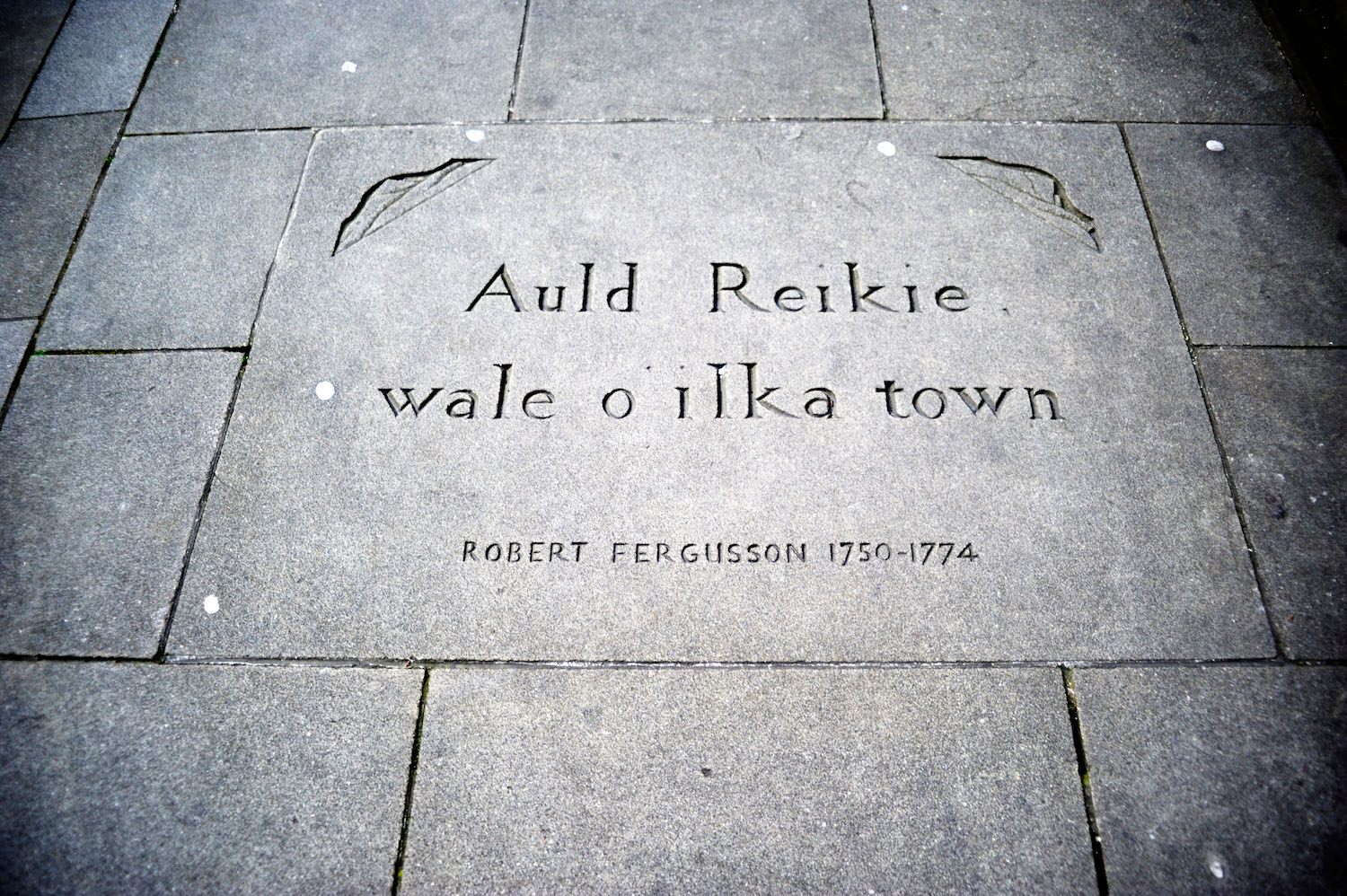

Over the next few centuries, Scots, which was the language of the southern Scottish people, began to creep north while Scottish Gaelic, the language of the north, retreated. By about 1500, Scots was the lingua franca of Scotland. The king spoke Scots. Records were kept in Scots. Some other languages remained, but Scots was by far the most important.

James VI came to power as the king of Scotland in 1567, but was related to Elizabeth I, ruling queen of England. When Elizabeth died, James became king of both Scotland and England in 1603, formally joining the two nations for the first time. (His name also changed, becoming James I.) He moved to London,* and, in a great tradition of Scotsmen denigrating their home country, referred to his move as trading “a stony couch for a deep feather bed.”

Scottish power was wildly diminished. The country’s poets and playwrights moved to London to scare up some patronage that no longer existed in Edinburgh. English became the language of power, spoken by the ambitious and noble. When the Reformation came, swapping in Protestantism for Catholicism in both England and Scotland, a mass-printed bible was widely available—but only in English. English had become not only the language of power, but also the language of divinity. “It’s quite a good move if you’re wanting your language to be considered better,” says Michael Hance, the director of the Scots Language Centre.

At this point it’s probably worth talking about what Scots is, and not just how it got here. Scots is a Germanic language, closely related to English but not really mutually comprehensible. There are several mutually comprehensible dialects of Scots, the same way there are mutually comprehensible dialects of English. Sometimes people will identify as speaking one of those Scots dialects—Doric, Ulster, Shetlandic. Listening to Scots spoken, as a native English speaker, you almost feel like you can get it for a sentence or two, and then you’ll have no idea what’s being said for another few sentences, and then you’ll sort of understand part of it again. Written, it’s a bit easier, as the sentence structure is broadly similar and much of the vocabulary is shared, if usually altered in spelling. The two languages are about as similar as Spanish and Portuguese, or Norwegian and Danish*.

Modern Scots is more German-like than English, with a lot of guttural -ch sounds. The English word “enough,” for example, is aneuch in Scots, with that hard German throat-clearing -ch sound. The old Norwegian influence can be seen in the converting of softer -ch sounds to hard -k sounds; “church” becomes kirk. Most of the vowel sounds are shifted in some way; “house” is pronounced (and spelled) hoose. Plurals are different, in that units of measurement are not pluralized (twa pund for “two pounds”) and there are some exception forms that don’t exist in English. There are many more diminutives in Scots than in English. The article “the” is used in places English would never use it, like in front of days of the week.

Almost everything is spelled slightly differently between Scots and English. This has caused some to see, just for example, the Scots language Wikipedia as just a bunch of weird translations of the Scottish English accent. “Joke project. Funny for a few minutes, but inappropriate use of resources,” wrote one Wikipedia editor on a Wikipedia comments page.

That editor’s suggestion to shut the Scots Wikipedia down was immediately rejected, with many Scots speakers jumping into the fight. But it’s not really that different from the way the ruling English powers treated the language.

There are, generally, two ways for a ruling power to change the way a minority population speaks. The first happened in, for example, Catalonia and Ireland: the ruling power violently banned any use of the local language, and sent literal military troops in to change place names and ensure everyone was speaking the language those in power wanted them to speak. This is, historically, an extremely bad and short-sighted strategy. This sort of blunt action immediately signifies that these minority languages are both something to fight for and a unifying force among a population. That usually results in outright warfare and underground systems to preserve the language.

What England did to Scotland was probably unintentional, but ended up being much more successful as a colonization technique in the long run. The English didn’t police the way the Scottish people spoke; they simply allowed English to be seen as the language of prestige, and offered to help anyone who wanted to better themselves learn how to speak this prestigious, superior language. Even when the English did, during the age of cartography, get Scottish place names wrong, they sort of did it by accident. Hance told me about a bog near his house which was originally called Puddock Haugh. Puddock is the Scots word for frog; haugh means a marshy bit of ground. Very simple place name! The English altered place names, sometimes, by substituting similar-sounding English words. Scots and English are fairly similar, and sometimes they’d get the translation right. For this place, they did not. Today, that bog is called “Paddock Hall,” despite there being neither a place for horses nor a nice big manor house.

This strategy takes a lot longer than a linguistic military invasion, but it serves to put a feeling of inferiority over an entire population. How good a person can you really be, and how good can your home be, if you don’t even speak correctly?

Scots is a language and not a dialect, but this strategy is not too dissimilar from what happens with African American Vernacular English, or AAVE, in the United States. Instead of recognizing AAVE as what it is—one American English dialect among many—education systems in the U.S. often brand it as an incorrect form of English, one that needs to be corrected (or as a “second language”). It isn’t different; it’s wrong. Inferior. This is a wildly effective, if subtle, ploy of oppression. “There are plenty of people in Scotland who actually think it’s a good thing,” says Hance. “The narrative is, we’ve been made better through this process.”

The Scottish people even have a term for their feeling of inferiority: the Scottish cringe. It’s a feeling of embarrassment about Scottish heritage—including the Scots language—and interpreting Scottishness as worse, lower, than Englishness. “Lots of Scottish people think to demonstrate any form of Scottish identity beyond that which is given formal approval is not something that should be encouraged,” says Hance.

Scots faces a unique and truly overwhelming set of obstacles. It’s very similar to English, which allows the ruling power to convince people that it’s simply another (worse) version of English. The concept of bilingualism in Scotland is very, very new. And English, the ruling language is the most powerful language in the world, the language of commerce and culture. More than half of the websites on the internet are in English, it is by far the most learned language (rather than mother tongue) in the world, is the official language for worldwide maritime and air travel, and is used by a whopping 95 percent of scientific articles—including from countries where it isn’t even a recognized official language. Until very recently, says Hance, even Scottish people didn’t think their language was worth fighting for; today, the funding to preserve Scottish Gaelic outstrips that for Scots by a mile.

Amid all this, Scots is defiantly still here. In the 2011 census, about 1.5 million of Scotland’s 5.3 million people declared that they read, spoke, or understood Scots. “Despite being in this situation for centuries, we kept going,” says Hance. “We still exist. We’re still separate and different, and have our unique way of seeing the world and our unique way of expressing it.” Scots isn’t endangered the way Scottish Gaelic is; it’s actually growing in popularity.

Census data isn’t always as clear as it might sound. There are people who only speak Scots, and can probably understand English but not really speak it. There are people who are fully bilingual, capable of switching, with awareness, between the languages. Some people will start a sentence in Scots and finish it in English, or use words from each language in the same conversation. There are those who speak English, but heavily influenced by Scots, with some words or pronunciations borrowed from Scots.

Technology has been a boon for the language, for a host of different reasons. Spellcheck has been a headache; computers and phones do not include native support for Scots, even while including support for languages spoken by vastly fewer people. (There are a few university research projects to create Scots spellcheck, but they’re not widespread.) But this has had the effect of making Scots speakers ever more aware that what they’re trying to type is not English; the more they have to reject an English spellcheck’s spelling of their Scots, the more they think about the language they use.

The informality of new forms of communication, too, is helping. Pre-email, writing a letter was a time-consuming and formal process, and the dominance of English as a prestige language meant that native Scots speakers would often write letters in English rather than their own language. But texting, social media, email—these are casual forms of communication. Most people find it easier to relax on punctuation, grammar, and capitalization when communicating digitally; Scots speakers relax in that way, too, but also relax by allowing themselves to use the language they actually speak. “Texting and posting, those are largely uncensored spaces, so the linguistic censorship that used to take place when you communicated with other people in written form, it doesn’t happen any longer,” says Hance. “People are free to use their own words, their own language.”

Scots is still wildly underrepresented in television, movies, books, newspapers, and in schools. Sometimes students will, in a creative writing class, be allowed to write a paper in Scots, but there are no Scots-language schools in Scotland. The lack of presence in schools, though, is just one concern Scots scholars have about the language.

“In general, it’s better now,” says Kay, “but it’s still not good enough.”

*Correction: We originally said English and Scots are about as similar as Finnish and Swedish. Norwegian and Danish is a much more accurate comparison. We also said that James I dissolved the Scottish parliament, but this happened after his death.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook