The Secret Paths That Led Ireland’s Catholics to Forbidden Mass

Passages to salvation from a time of persecution.

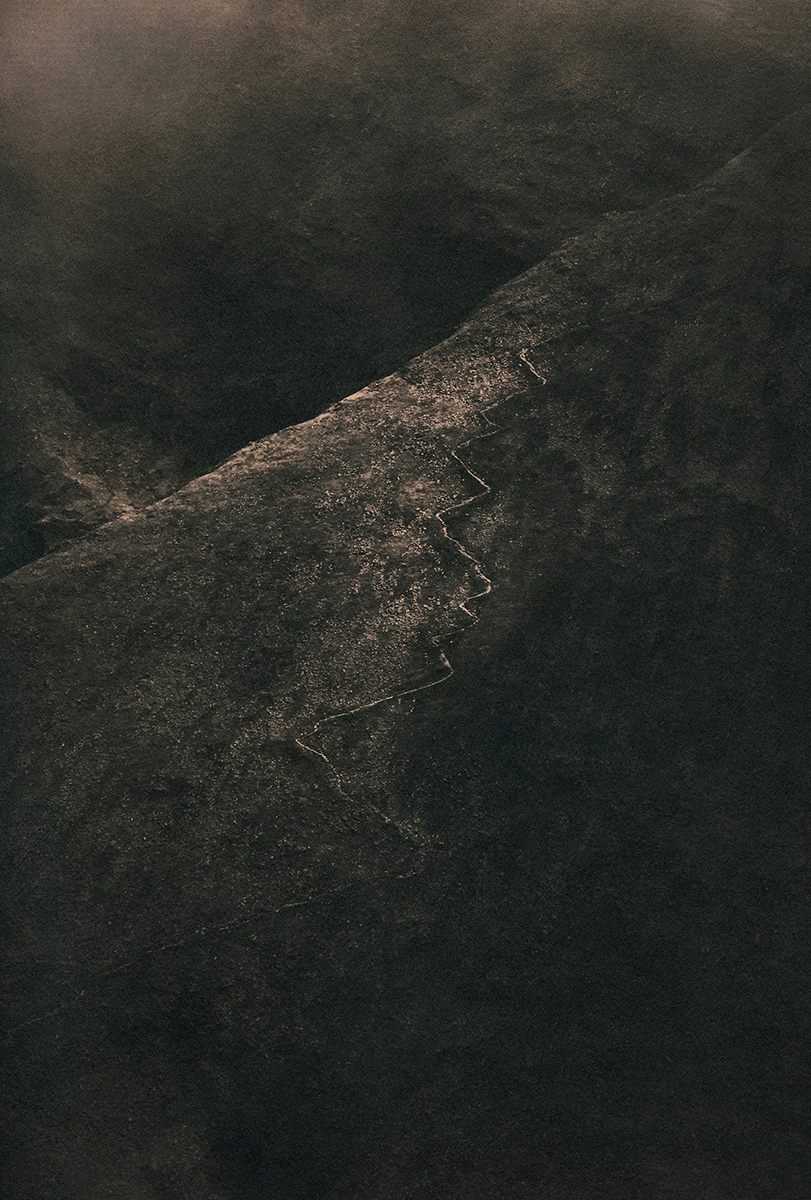

On Ireland’s southwest coast, in County Kerry, there is a small village called Caherdaniel. Nearby, there is a national park, a fort that offers glimpses of the Skellig Islands, and the sloping shores of Derrynane Bay. And, etched into this countryside, is the Caherdaniel Mass Path. Like other such paths around Ireland, this narrow track was used by Catholics to attend mass 300 years ago, during a time of religious persecution.

The locations of these passages were closely held secrets, which is why it took Irish photographer Caitriona Dunnett years to research her project Mass Paths. It was the one at Caherdaniel that first sparked her interest. “I photographed it and remembered learning about the penal times at school,” she says. “It inspired me to research and find other penal paths to photograph.”

Beginning in the 1690s, the Protestant-controlled Irish Parliament, in conjunction with the English Parliament, passed a series of increasingly stringent, brutally wide-ranging penal laws that imposed serious restrictions on the already oppressed Catholic majority. No Catholic person could vote, or become a lawyer or a judge. They could not own a firearm or serve in the army or navy. They could not set up a school, or teach or be educated abroad. They could not own a horse worth more than £5. They could not speak or read their native Gaelic.

In an attempt to decrease Catholic land holdings, in the early 1700s, a new law prohibited primogeniture, and instead, when an Irish Catholic died, his land was divided among his sons and daughters. But any son who became Protestant could inherit everything. According to one report, Catholics made up 90 percent of the country’s population. A the end of 1703, they owned less than 10 percent of the land.

Catholic bishops were forced to leave the country. One priest per parish could remain, if he registered with the authorities. The rest were banished, and any who returned would be executed. In 1709, another law was enacted that forced priests to take an oath of abjuration to Protestant Queen Anne. Only 33 priests are recorded to have taken this oath, and the rest had effectively been outlawed. The law also forced people to declare where and when they had attended mass during the prior month, and report any hidden clergy.

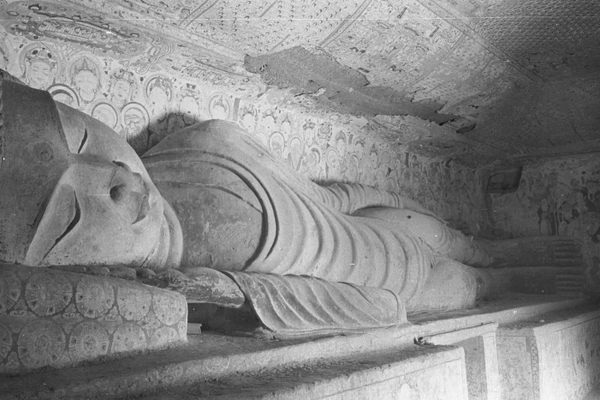

These hidden priests held mass in secret, away from watchful eyes. It might be in a shed, or outdoors, with a rock as an altar. Priests sometimes obscured their faces, so if anyone in attendance was later questioned, they could honestly assert they did not know who had led the mass. Priest hunters, who received a bounty for any bishop, priest, or monk they captured, created further peril.

Mass attendees were at similar risk. Some walked to mass along streams, to mask their footsteps, while many took these secret mass paths to worship. Penal law reforms began late in the 18th century and continued throughout the 19th century, but it was only in 1920 that the last laws were finally repealed.

Dunnett’s project Mass Paths will be exhibited at the Custom House Studios and Gallery in Westport, County Mayo, Ireland, from March 22 to April 15, 2018. She is also running a crowdfunding campaign. Atlas Obscura spoke to the photographer about memory and landscape, researching oral histories, and how she produced her evocative images.

Given that these paths were secret, how did you find them?

The locations of these paths were traditionally passed on by word of mouth and local knowledge handed down through generations. I discovered the paths by doing searches on the Internet and finding little snippets posted by schools doing projects on local history, parish newsletters informing congregations about annual mass at the mass rock, and walking clubs that give directions, using penal sites as way-markers. These fragments led me to local maps and hunts for locations, which were hidden in the landscapes. Some paths were easily found, while others were not so straightforward! In those circumstances, I was lucky to find very helpful local people who directed me.

Did you find any remnants of the places where mass was held?

There are a lot of penal sites remaining in Ireland and some of my photographs document physical remnants of the places where mass was held, such as mass rocks. Some parishes still remember these sites by holding an annual mass at their local rock.

How did it feel to retrace these paths?

A few paths stand out from the others for being physically challenging, in particular Cnoc Na Toinne Mass Path in County Kerry. I remember thinking how committed people must have been to climb this path on a regular basis. Young and old would have walked it in all types of weather. I didn’t connect with the faithful’s fear of being discovered or the ensuing consequences, but I did sense a hope, a hope of trying to keep something alive. I came across a few very special mass rocks that emitted a sense of peace and tranquility.

Did you learn of any individual stories, either of worshippers or priests?

There is a plaque on Alt an tSagairt (Priest Mountain), in the Mourne Mountains, commemorating Father O’Hagan and his congregation, who were murdered by Cromwellian soldiers. This mass rock is situated 1,362 feet above sea level and has commanding views across County Down. It’s an impressive place with a very sad history. The story goes that a priest hunter spotted the group and alerted the soldiers. Priest hunters roamed the country during this period looking for, and murdering, priests for a cash bounty. There are also lots of ghost stories about mass paths and rocks. You are not supposed to build on a mass path, and those unlucky enough to live on one say they have experienced spectral events at night. Walkers also tell stories of coming across ghostly priests and their congregations at penal sites.

Tell us a little about the image production process, and why you decided on this treatment.

The project developed over a few years and it took a bit of experimentation to find the right printing procedure. When I started Mass Paths, I was working on another project using digital contact negatives, and I decided to try this approach. I printed cyanotypes, an early photographic technique introduced by John Hershel in 1842. The cyanotype has a blue Prussian color and I explored the effect of different toners on it. I tried a variety of toners, different teas, coffee, and tannic wine, before choosing black tea.

My photographs were shot with a digital camera and converted into negatives using Photoshop. The negatives were printed onto acetate, then contact-printed onto paper coated with the cyanotype formula, using a UV light box. The prints are fixed in a bath of vinegar and water, and then washed in water. I then tone my prints in a bath of tea for a few hours.

The cyanotype printing and subsequent toning became important in communicating the heart of the Mass Paths project. I like the idea of the process being layered like the Irish landscape, which has been coated over time by personal and national narratives.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook