Soil Scientists Dig Deep to Understand the ‘Skin of the Earth’

What’s beneath our feet is crucial to life on the planet—don’t you dare call it dirt.

Stephan Mantel was on a quest. As he disembarked from the third flight since leaving Amsterdam, the tropical heat enveloped him. He had arrived in Putussibau, in the heart of Borneo, Asia’s largest island.

A local guide and two hired helpers joined him for an hour-long journey along tributaries of the Kapuas River. Their boat, made from a hollowed-out tree trunk, sat so low that Mantel could trail his hand in the water. They docked and trekked deeper into the wilderness, where a thick layer of leaf litter and decay on the forest floor emitted a faintly rotten smell. Mantel searched for the right place to dig. He bored into the earth with an auger at various promising spots, only to abandon the location when the tool hit rock. This was no expedition for artifacts or hidden treasure. Mantel was intent on extracting the earth itself, in a vertical slice of soil.

If the team’s effort succeeded, the sample would end up as a meticulously preserved, five-foot-long slab, or monolith, at the World Soil Museum in Wageningen, Netherlands, which Mantel heads. The museum is the public face of the research institute ISRIC World Soil Information, with the most diverse soil repository of its kind: some 7,000 soil samples, including 1,200 monoliths from 85 countries collected over more than five decades. The museum is the most comprehensive of more than 100 similar collections worldwide, ranging from modest, single rooms to permanent exhibits within larger natural history museums. All of them aim to give visitors a better understanding of soil and how it is essential to life on Earth.

“Most people don’t know anything about soil,” says Dominique Arrouays, a soil scientist at the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food, and Environment in Orleans, France. “In the city, they never see the soil, unless there’s construction. It’s all pavement. They don’t realize that everything depends on soils.”

Soils grow the food that provides an estimated 98.8 percent of our daily calories, according to a 2019 paper in Environment International, and house more than 25 percent of the world’s biodiversity. Soils also store massive amounts of both fresh water and carbon.

But soils are in trouble. According to a 2015 United Nations report, a third of the planet’s soil is moderately to highly degraded thanks to acidification, erosion, and other factors. Soils cannot be regenerated quickly: It may take up to 1,000 years to produce a couple centimeters of soil. And yet many people dismiss it as nothing more than dirt.

Arrouays grimaces at the word. “Soil is not dirt. Soil is the skin of the earth,” he says. “It’s not something dirty. We need to protect it.”

Back in the Borneo rainforest, Mantel selected a site not because it was unique, but because it was so typical, representing the entire surrounding landscape, and documented details such as its vegetation and slope. His team used hoes to dig for three hours, reaching a depth of two meters down into the layered bands called horizons. Mantel took notes about each horizon’s color, texture, structure, and biological activity, and extracted a one-kilogram sample from each layer.

The workers then hewed a single, intact column and stabilized it to prevent crumbling as they slowly detached it from the pit wall. Once wrapped in cloth and nestled in a wooden box, the column of soil, weighing more than 200 pounds, was carried back to the boat, the box slung on a pole between the men. It would join samples from other sites on a long journey from Borneo to Wageningen.

At the World Soil Museum’s lab, the slab was air-dried, losing about half its weight. Secured to a long wooden board, the column, now a monolith two inches thick, was hardened and preserved with a coating of diluted glue.

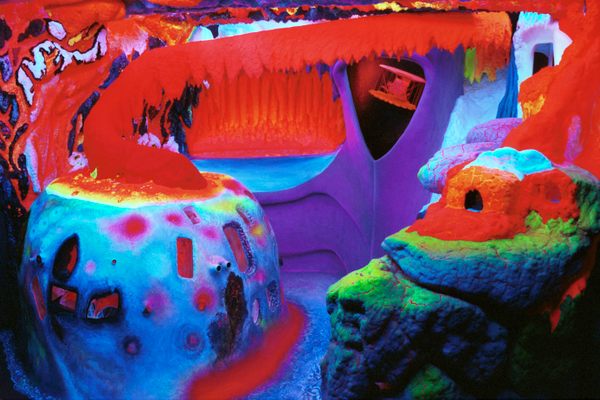

The museum displays about 90 of these monoliths: Minerals, organic metals, water content, and other factors give their horizons a range of vibrant colors. Dark green, for example, indicates the mineral glauconite, and hints that the soil may have once been part of a sea floor. Blue hues suggest the soil was poorly drained, perhaps waterlogged. There is even a deep purple soil from Zambia, resulting from a combination of iron oxides, aluminum, and manganese.

“When you enter the museum, the most heard word is ‘Wow,’” says Mantel. “People are surprised by seeing so much diversity.” On tours and in conversations with visitors, he shares stories that show how, like tree rings and rock formations, soils are a record of history. “I want them to have something to tell at the dinner table later in the evening,” says Mantel.

For example, a monolith from a peat landscape in Iceland documents activity from the island’s volcanoes. Near the bottom of the mostly dark brown column, a wide band of white indicates an eruption from 2,800 years ago. A layer closer to the top is speckled with ash from the Laki volcanic fissure, which erupted for eight months beginning in June 1783. That volcanic event threw enough dust into the atmosphere to disrupt the global climate for a decade, lowering temperatures and causing crop failure and famine. Food shortages in France led to political unrest: The soil, says Mantel, shows how an Icelandic volcano helped spark the French Revolution in 1789.

“On the one hand, soil is so difficult to explain and so complex,” says Mantel. “But on the other hand, I find it’s very easy to fascinate people once they’re in the museum.”

Researchers gravitate to the museum to study the hundreds of monoliths not on public display, as well as the thousands of soil samples, each analyzed, dried, sieved, and then stored in barcoded glass containers. And for scientists who can’t make the trip, there’s the postal service, though Mantel and his staff take care to vet each request. The samples, while free of cost (researchers only pay for shipping), are a valuable and finite resource.

“On occasion, we have run out of a soil sample,” says Mantel. “And once it’s gone, there’s no substitute. It’s precious material.”

French soil scientist Arrouays notes that, in addition to their scientific value, the monoliths at the museum have another appeal. “Choosing which soil and creating the soil profile is an art,” he says. “Just like a photographer taking a photo. You’re taking the beauty of the earth and capturing it.”

“Soil certainly has an aesthetic aspect,” says Mantel. He recalls visitors, at the museum for one of the exhibits that grew from its regular collaborations with artists, pausing to look at the monoliths.

“You could tell from the way they behaved and their clothes, they were art lovers,” he says. “They would stand in front of the soil profiles and say, ‘Wow, the beauty of the earth.’ They would see them as art objects.”

In fact, contemporary artists worldwide are working with soil as a medium, says Christian Feller, a soil scientist at the Institute of Research for Development in Montpellier, France. In addition to its range of color and texture, soil appeals to many artists because it connects us to the natural world.

“When artists incorporate soil, they are ambassadors of soil,” says Feller. “In soil museums, one of the functions of the monoliths is to show that soil is beautiful.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook