Solving the Mystery of Early Polar Exploration Through Stamps

Every year, new mail emerges from the world’s attics that gets decoded by a dedicated band of philatelists.

A glimpse into Admiral Richard Byrd’s 1928-30 first Antarctic expedition. (Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild/CC BY-SA 3.0)

It’s a mild afternoon, sunlight meandering through the windows. You’ve finally gotten around to doing a little attic inventory, and armed with dust cloth and waste bin, you survey the files and folders, boxes and briefcases that scatter the floor.

Between old tax returns, yearbooks, clothing from god-knows-where, and back issues of magazines long since folded, you find an envelope, slightly moldy and frayed at the edges, with an arrangement of stamps and strange postal marks, not from any recognizable country. What is it?

Strangely, an errant piece of mail might be a vital historical document. All around the world, important documentation about early exploration to the North and South Poles hides in boxes and binders. You might just be in possession of a paper artifact revealing a polar expedition that has been, up until now, lost to snow and ice.

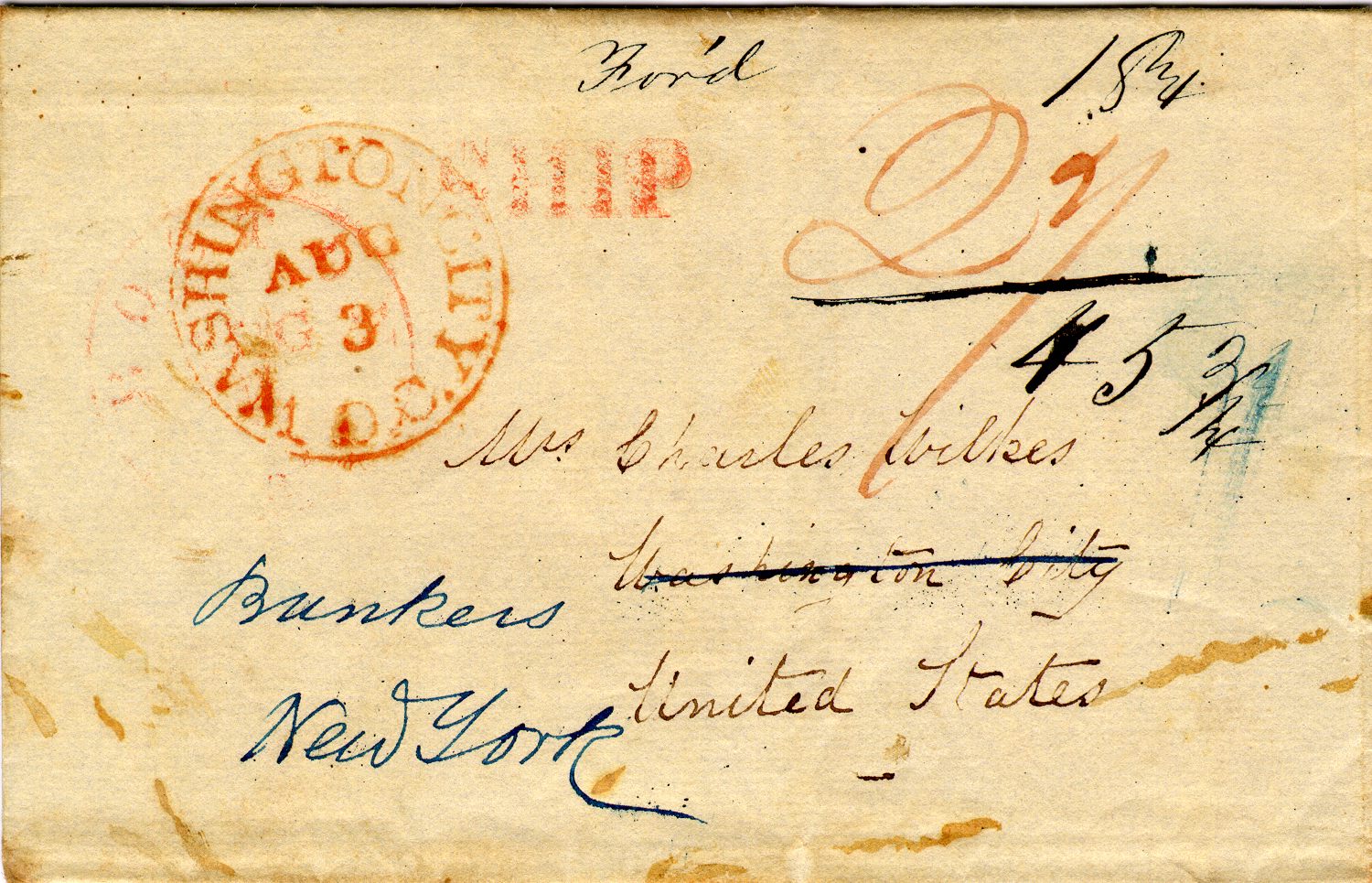

A letter from American Charles Wilkes to his wife in Washington, DC, sent during his pioneering 1838-42 expedition to the South Pole. (Photo: Courtesy of Hal Vogel)

Just about every year since the 1980s, an illuminating piece of polar post turns up in someone’s attic, according to Hal Vogel, vice president of the American Society of Polar Philatelists (ASPP). The ASPP is an organization of 220 independent philatelists—stamp collectors— interested in mail and polar history. The group, founded in 1956, shares findings and updates through a quarterly publication, the Ice Cap News, and meets at an annual convention, where top exhibitors are handed out awards based on the quality and rarity of their artifacts. Mostly, though, members of the ASPP, who come from nearly 20 different countries, seek out and pore over envelopes and stamps sent home from exploratory expeditions, ships, and research stations in the world’s two extremes, mostly dating from the late 1800s to early 1900s.

Polar philately, the art of studying delicate slips of paper that have withstood thousands of miles and perhaps hundreds of years, provides a glimpse into the sheer bravado of the age of polar exploration. Polar philatelists are lured by that same mystery that lured the pioneering polar explorers—a shared fascination with a harsh and vast unknown.

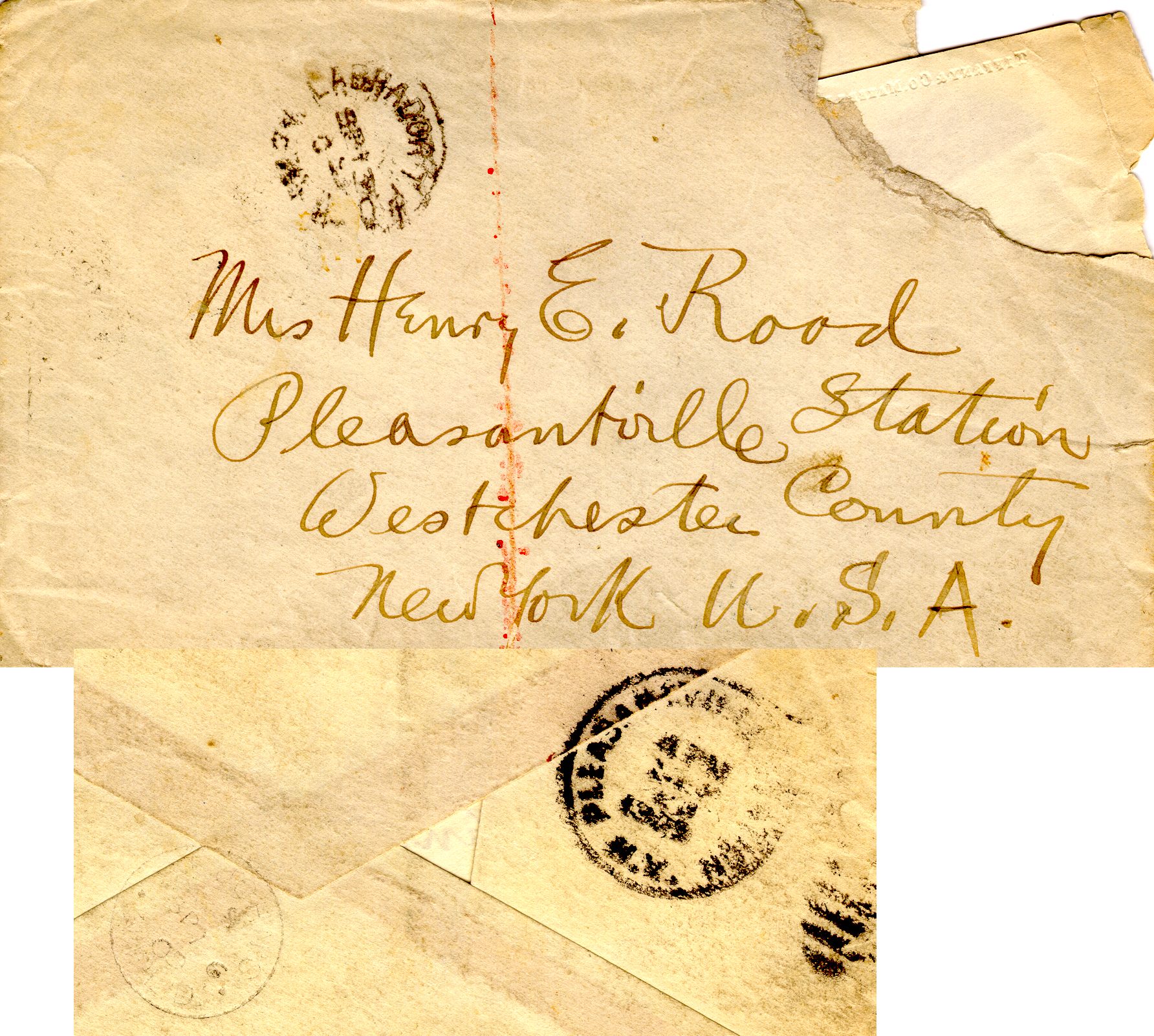

A letter dispatched to the wife of Adolphus Greely during his 1881-84 Lady Franklin Bay expedition. (Photo: Hal Vogel)

In the hands of the expert philatelists, each letter dispatched from the far reaches of the North or South Pole might hold some clue to life on the outer edges of Earth—a special edition stamp, perhaps, or a missing last will and testament, musings that might shed new light on a recorded expedition, or reveal a completely unknown event.

The historical gaps come, according to Vogel, due to the lack of human witnesses to life on the poles. The earth’s southernmost continent did not even become known as “Antarctica” until 1890, thanks to British cartographer and geographer John George Bartholomew.

It was as a boy growing up in the 1950s that Vogel discovered canceled envelopes and postcards as unique, individual ways to document history. By age 12, he began to wonder: how do you get mail to the South Pole? While watching a program on his home’s black and white television set, he saw something about an explorer headed to the South Pole. He sent the explorer, Dr. Paul A. Siple, a letter, and 18 months later, Vogel received a reply from the man’s assistant. “I supposed that was one of the first letters sent from the new South Pole post service,” Vogel says. It got him hooked.

Eric Marshall, Frank Wild and Ernest Shackleton bundled up at a new Farthest South latitude in January 1909. (Photo: J. B. Adams/Public Domain)

These polar explorers were the astronauts of their time, says Vogel. “They were exploring conditions, lands, science, people, that in some cases were totally new and unknown. They did have an element of hazard—in many cases, extreme hazard.” In a group of 21, only seven might return, as with the instance of the Lady Franklin Bay Expedition (1881-84).

The early polar adventurers faced grave dangers on their trips—“You can only make one mistake on a polar expedition,” says Vogel. In some cases, entire expeditions disappeared, a letter home possibly being one of the only traces left behind. It brings to mind a British voyage to the Arctic in 1845 known as Franklin’s lost expedition. Of the 129 men who set out together, not one returned. It was in Disko Bay, on the west coast of Greenland, that crew members wrote their final letters home, giving us glimpses into the mind of an adventure unaware of its own imminent failure.

In some ways, the polar regions transport us back in time, to concerns over communication, safety, and sovereignty that have already been resolved elsewhere.

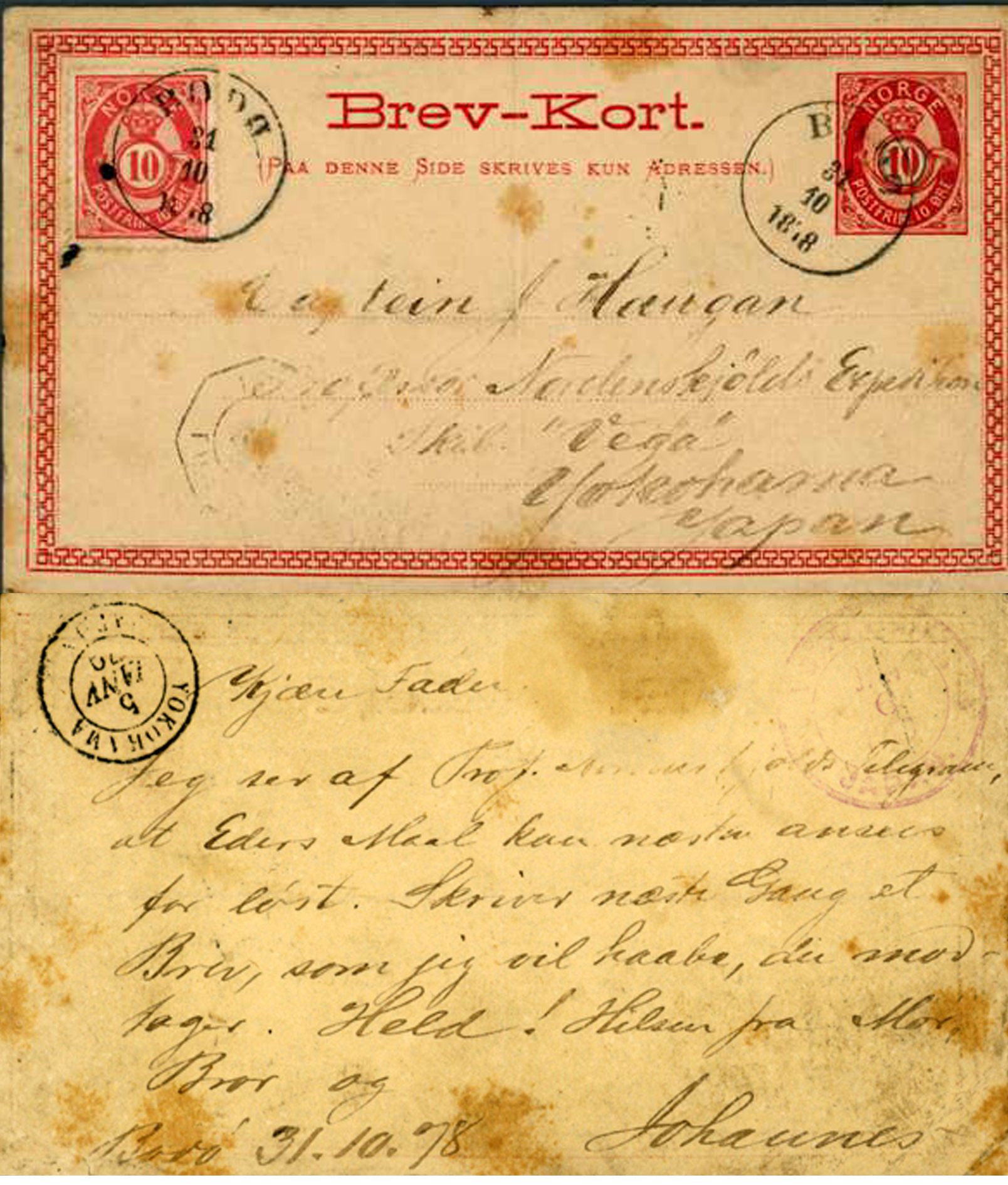

A polar artifact from the 1878-80 Vega Expedition, the first to navigate through the Arctic’s Northeast Passage. (Photo: Hal Vogel)

Mail itself began around the 15th century, but no one ventured near the North or South Pole until the late 1800s—let alone sent a letter from out there. The first fully government funded American expedition was not until 1881, one of the country’s two major contributions to the First International Polar Year (1882-83). The first successful trips to the North and South Pole were not for another four decades, taking place in 1909 and 1911. The U.S. postal service was established in 1775, but it would be nearly two centuries before post reached the poles.

The U.S. Navy put a post office at the South Pole in 1956, perhaps as more of a publicity stunt or geopolitical move than as a practical matter—trumpeting the ability to send mail from the bottom of the world. Mail could only make it in and out by airplane, an impossible feat in the Antarctic winter.

Admiral Robert Peary during his 1891-1892 expedition to Greenland. (Photo: Frederick Cook/Public Domain)

“I was interested in documenting what we might call the pre-philatelic period,” says Vogel. “Up to the end of World War II, we had very little knowledge of mail related to these polar expeditions.” As the decades went by, more mail originating from the poles, though not necessarily sent through the formal postal system, began to be discovered. Vogel collected all of his findings in a book, Essence of Polar Philately, published by the ASPP in 2008. It presents lists and explanations of material that documents the various polar expeditions, some of which had never been heard of before. Vogel says that it’s been called “the Bible of polar philately.”

More routine discoveries can still yield extraordinary findings. For instance, not all the crew members on the First Byrd Antarctic Expedition (1928-30) were accounted for in the expedition’s records—a man named John Morrison being one example. The only reason that we know Morrison was aboard at all is thanks to mail he sent from their ship, the Eleanor Bolling.

Here are three other cases of polar stamp detective work:

BICKMORE

One of the great stories in polar philatelic discovery is that of Albert Smith Bickmore, a zoologist and a founder of the American Museum of Natural History. From 1864-67, Bickmore was on a one-man scientific expedition researching shells, stones, and ethnology in the South Pacific (today’s Indonesia and Malaysia). In his subsequent book, Travels in the East Indian Archipelago (1868), Bickmore only mentioned spending time in the Dutch East Indies and China—yet a piece of post would prove otherwise.

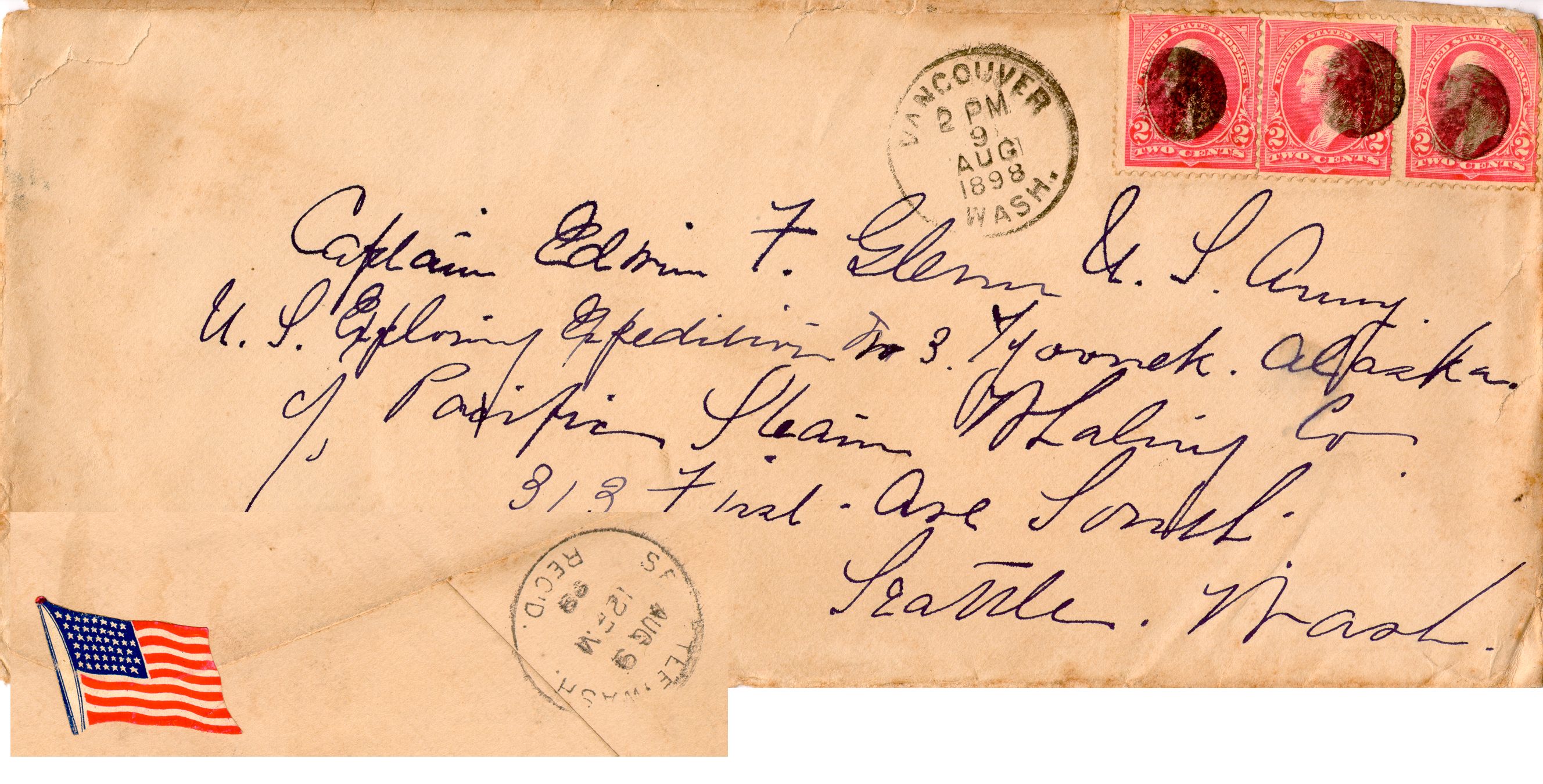

A piece of inward mail from the wife of the leader of 1898 U.S. Army Alaska Exploring Expedition No. 3. (Photo: Hal Vogel)

When Bickmore’s envelope initially resurfaced, it had drawn philatelic attention for its unique transit marks, which revealed a rare rate period in the postal relationship between Hawaii and the continental U.S. The transit marks also revealed an amazingly long and circuitous postal route—overseas from Siberia to Hawaii, from Hawaii to San Francisco, and then overland another 3,000 miles to Maine. But the international missive exposed yet more: a phase of Bickmore’s explorations previously unknown.

It was not until later, when Bickmore’s letter caught the attention of polar philatelists, that a new puzzle piece was found. Its transit marks showed that the letter had been posted by Bickmore from Siberia, in the Russian Arctic—a pit stop left unmentioned in his book.

PEARY

Venturing further northward beyond Bickmore’s trip to Siberia, you will come upon Admiral Robert Peary’s 1909 attempt at the North Pole. Peary had been trying to reach the North Pole for two decades by this point, and he’d lost nearly as many toes as he’d spent years trying. He had sent a letter to his attorney as he was traveling north to Greenland in which he set forth, in effect, his last will and testament in case he didn’t return. For a long time, nobody knew if Peary had been successful, or had even survived—and if he hadn’t, that piece of mail would have been our last record of him.

The first mail from Newfoundland from the reporter who had just interviewed Robert E. Peary after his North Pole success. (Photo: Hal Vogel)

But Peary did return alive, and when he descended to Battle Harbor, Newfoundland, he dispatched an announcement and then simply sat and waited for the journalists to flock. Perhaps the most prized pieces of mail from Peary’s great triumph are the letters from journalists claiming to be the first to board his ship for an interview.

WILKES

Another instance of polar mail that deserves an almost mythical status are the messages from the leader of the expedition that confirmed the existence of Antarctica as a continent.

It was a trip that lasted from 1838 to 1842, led by U.S. naval officer Charles Wilkes, known as the Wilkes Antarctic Expedition. Wilkes’ crew surveyed and reported land along the Antarctic barrier land mass, and a part of the region duly became known as “Wilkes Land.” Their trip provided the first proof of an Antarctic continent—and indeed, “Wilkes Land” came to exist in geographical parlance before the term “Antarctica” itself.

Schooner A.W. Greely frozen in for the winter of 1937-38 near Etah, Greenland during the MacGregor Arctic expedition. (Photo: Bobhaybob/CC-BY-SA-3.0)

The niche art of polar philately is a reminder of how little we know and how little we are. Two centuries ago, the earth’s two poles were unmapped and unknown. Yet in the 19th century, they drew uncounted Arctic explorers, many of whom did not return and of whom we have no record. Most details of their journeys will forever be unknown.

But to think: back in the dark, dusty corner of that moldering box, a new detail might just be discovered.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook