How the USSR Turned Houses of Worship Into Museums of Atheism

In these Soviet churches, religion was banned.

You can almost see the devotion worked into the stones of the Kazan Cathedral of St. Petersburg. It’s stately and imposing, with a colonnade made up of dozens of red granite columns, stretching along one magnificent semicircle. Completed in 1811, the church was inspired by St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, and consecrated to one of the most important figures of the Russian Orthodox church: Our Lady of Kazan, the venerated icon representing the Virgin Mary.

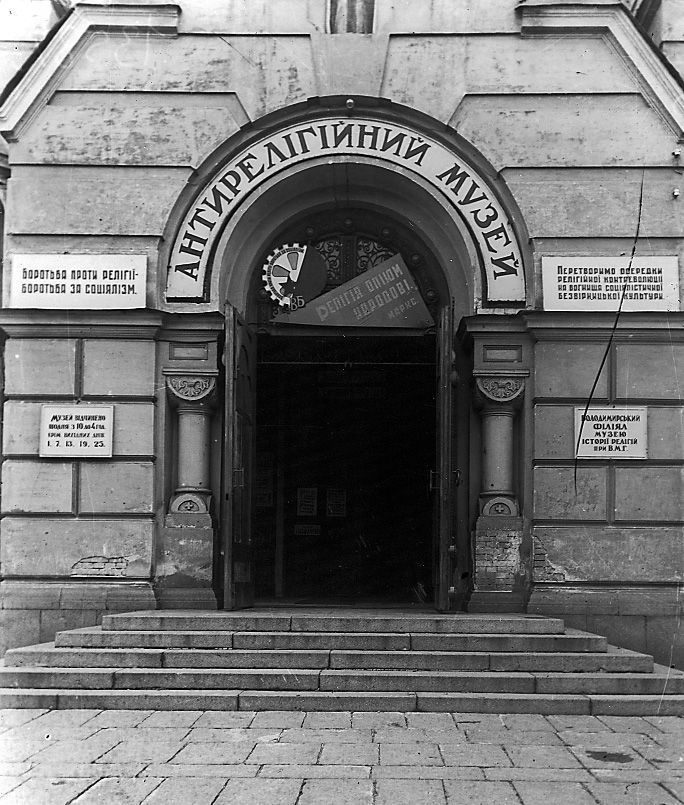

But 15 years after the Russian Revolution, in January 1932, the cathedral was closed. When it reopened in November, it had a wholly different icon at its helm. This giant edifice was now a temple of atheism, one of hundreds of anti-religious museums in the Soviet Union’s former churches, synagogues, and mosques.

In the decades after the Russian Civil War, the Bolsheviks struggled to find the best way to establish a climate of atheism across the Soviet Union. At first, many hoped and believed that religion would naturally disappear once the social change they hoped to bring about came into effect. But though church jewels and other valuables had been plundered and nationalized, members of the clergy arrested, and saints’ relics exhumed and put on show to disprove their apparent incorruptibility, people continued to believe.

As time went on, Leninists in the party realized they would have to take active steps to stamp out religion for good. At the 15th party conference in late 1927, Joseph Stalin criticized what he perceived to be a “slackening in the struggle against religion,” and pushed for more stringent anti-religious policies. At the highest level, this ranged from forbidding educated believers from becoming Communist party members to the mass slaughter of thousands of Russian Orthodox priests and bishops.

But on the ground, the party wanted to encourage ordinary workers to renounce their faith. The outcome was a boom in anti-religious, pro-scientific propaganda: posters, booklets, films, radio programs, public lectures, city tours, and scientific observatories. In the late 1920s, the government agency tasked with this challenge, the Commissariat of Enlightenment, landed upon a new tactic. These were the museums of atheism.

Initially, there were just 30 anti-religious museums across the great expanse of the Soviet Union. But within four decades, there were hundreds of them, housed in the country’s most significant former monasteries and places of worship. Some of the most famous were in Moscow and St. Petersburg’s majestic former Orthodox cathedrals—more accessible to foreign tourists than those in more distant cities. But the museums existed throughout the country and across houses of worship from all religions, including Ukrainian mosques and Siberian Buddhist temples.

The key, according to the historian Victoria Smolkin, was to transform a sacred place into a sanitized place of learning. “They were considered most effective,” she writes in A Sacred Space Is Never Empty: A History of Soviet Atheism, “when they occupied religious spaces that had been repurposed for atheist use.”

In the early days of the Soviet Union, government officials began to conceive of museums in an entirely different way. They were not simply a way to put objects on display, but tangible, even enjoyable, ways to educate the public, help peasants understand their history, and fill their visitors with enthusiasm for the glorious communist future that lay ahead. Consequently, all kinds of museums underwent a tremendous overhaul, with ancient works swapped out for modern ones. To this end, nearly 250 new museums were opened between 1918 and 1923. The anti-religious museums were one small part of a grand educational plan, with what the curator and historian Crispin Paine describes as a clear ideological purpose: “the inculcation of a Marxist interpretation of history.”

Anti-religious museums adopted a three-prong line of attack. According to Paine, they would expose “the crimes and tricks of the clergy”; promote science as a modern analog to religion; and demonstrate how religion had been the “handmaiden of bourgeois capitalism.” It would have no place in the glorious future of the Soviet Union. More than that, Paine writes, “they adopted a deliberate policy of sacrilege,” where icons and relics were stripped of their mystique and treated as ordinary objects.

One particularly detailed account, from an American visitor in the late 1930s, vividly describes one of Moscow’s anti-religious museums. Charles Seely, a former naval officer, decided to pay a visit to the museum housed in the vast former Strasnoi Monastery. In these glorious surroundings, his Bolshevik tour guide promised him a miracle. “I, naturally, was interested, but I seriously doubted his ability to perform one,” he wrote, in a 1942 book that included his recollections of the USSR.

The guide showed him a large painting of the Virgin Mary. As Seely watched, her eyes began to grow damp and misty. Then, “the tears then ran down her cheeks in such a perfectly natural manner that any unsuspecting person would have readily believed that he was actually witnessing a miracle,” Seely wrote. “The tears were real enough to satisfy all but the most incredulous.”

Quickly, however, the illusion was ruined: “The demonstration was positively uncanny, but finally the guide spoilt everything by taking me around the painting and showing me how the priests formerly performed the ‘miracle’ by using an eyedropper.” These tears had previously spilled out on occasions where the church’s collection plate looked worryingly empty, he explained.

Other miracles were similarly exposed. The body of a high church dignitary, exhumed annually by the head of the Russian Orthodox Church and proclaimed to be exactly as it had been “when it died several hundred years ago,” was shown to be simply a bag of bones. In other cases, “incorruptible” bodies had been mummified by the cool, dry conditions of underground crypts. “The object of this colossal deception was to convince the people that miracles were still being performed,” Seely wrote. “Nobody doubted the Czar, of course, as he was the head of the Russian church.”

Throughout the museums, sacred icons from the Orthodox church were placed alongside so-called “primitive” statues and objects from around the world. They might include amulets, voodoo figures, or even the trappings of so-called “witch doctors” from faraway cultures. “If you grow up in an Orthodox society,” says Paine, “you are conditioned from childhood to revere icons and the other sort of material expressions of the Orthodox faith. And you are also brought up, often subconsciously, to feel a degree of contempt for so-called ‘tribal’ societies.” Putting the two together made an important, if racist, point: These familiar manifestations of belief are no more sophisticated than those from elsewhere in the world.

In the cellar of the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg, an entire exhibition was dedicated to the cruelty of religion, and the violent horrors of its history. Later, the historian Igor Polianksi writes, it would be copied in other anti-religious museums across the USSR. In one diorama, a torture chamber depicting the Spanish Inquisition showed a heretic bound on a rack. He awaits his punishment, as a hooded executioner presents him with an array of torture instruments: a thumbscrew; a two-headed heretic’s fork, which needles simultaneously into the chin and breastbone; a branding iron; and an agonizing Judas chair.

The museums systematically depicted religion of all kinds as a historical force for ignorance, racism and anti-semitism, and cruelty. Its only worthy replacement, they argued, was science.

Polianski describes how “panels, diagrams, dioramas, and models explaining comparative anatomy and embryology” were displayed alongside “fossils from dinosaurs and hominids, portraits of socialist ‘miracle doctors,’ and meteoric stones.” Man was connected not to God, but to nature: “Paradise apples,” bred by the famous Russian horticulturist Ivan Michurin, and statues of Ivan Pavlov and his Pavlovian dogs, were included to help make this point. As one interpreter remarked to two visiting French scientists, “We, gentlemen, prefer to put our trust in Science. You can see what the new Russia has achieved in Science: medicine, chemistry, physics, biology, stratosphere, aviation, industry. We don’t need religion to accomplish miracles.”

Foreign visitors seem divided on how to take these iconoclastic museums. Seely, for his part, left brimming with enthusiasm, and declared that “society would be measurably benefited if all ministers of the gospel, and all divinity students” could visit such a museum. Others were less delighted. Many of their accounts, Paine observes, seem to conclude that they museums were “naïve and embarrassing.” The apparently sad displays appeared even more mediocre set against their opulent holy surroundings.

But they were tremendously popular with Soviet visitors—though whether this was genuine interest in the future of atheism or simply a welcome break from the production line is unclear. Between 1956 and 1963, hundreds of thousands of people visited the former Kazan Cathedral—soaring from 257,000 visitors, in 1956, to 700,000 in 1963. Other museums around the country boasted similarly impressive attendance numbers. Often, people came on structured group tours, in which workers from factories or offices would come all at once for a guided visit: Some museums might have as many as 17 group tours in a day. By the late 1980s, the New York Times reported, the Sunday afternoon wait to enter the Kazan museum might be as much as two hours.

But despite it all, militant atheistic fervor failed to take hold. In some parts of the country, religious practices continued, gently humming away in the background. Though places of worship had theoretically been confiscated and closed, groups were still able to rent them from the government for religious services, paying a larger fee for a more extravagant setting. Other people simply lapsed into a kind of religious apathy. Scientific atheism was taught in schools, alongside history and geography, but in a 1975 survey, many people still professed to find atheistic dogma boring.

By 1987, the Times reported, “Soviet officials have begun to admit that they may be losing the battle against religion.” For decades, Bibles had been forbidden, and religious education virtually non-existent—but militant atheism does not appear to have been a sufficiently captivating force to take its place. From the late 1970s, the paper reported, with the 1917 revolution a distant memory, a burgeoning “religious revival … [had] grown up to fill the ideological void.” A poll of young people showed “a growing fascination, especially among the well-educated, with religious literature and services.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, most of its anti-religious museums went with it. A few still exist, rebranded as Museums of Religion, but they have either been moved to new settings or relegated to a single wing of the religious institutions they once inhabited. Almost every closed church and temple in the Soviet Union has since been returned to its original purpose.

The museums didn’t just attempt to bring down religion, Polianski writes, but to portray atheism as a source of joy—“not only a negation of religion, but a positive creative force bringing happiness.” In the end, however, people failed to believe in the power of the cult of disbelief.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook