The Soviet Children’s Books That Broke the Rules of Propaganda

How folk tales and traditional life snuck into avant-garde kids’ books in the 1930s.

Natalia Chelpanova was 20 years old in 1917, when the Russian Revolution transformed her country. As an art student, she became part of the new VKhUTEMAS (Vysshie khudozhestvenno-tekhnicheskie masterskie, or Higher state artistic and technical studios)—the state school also known as the “Soviet Bauhaus.” There, she studied under avant-garde artists steeped in ideas about abstract art and the role of art in social movements.

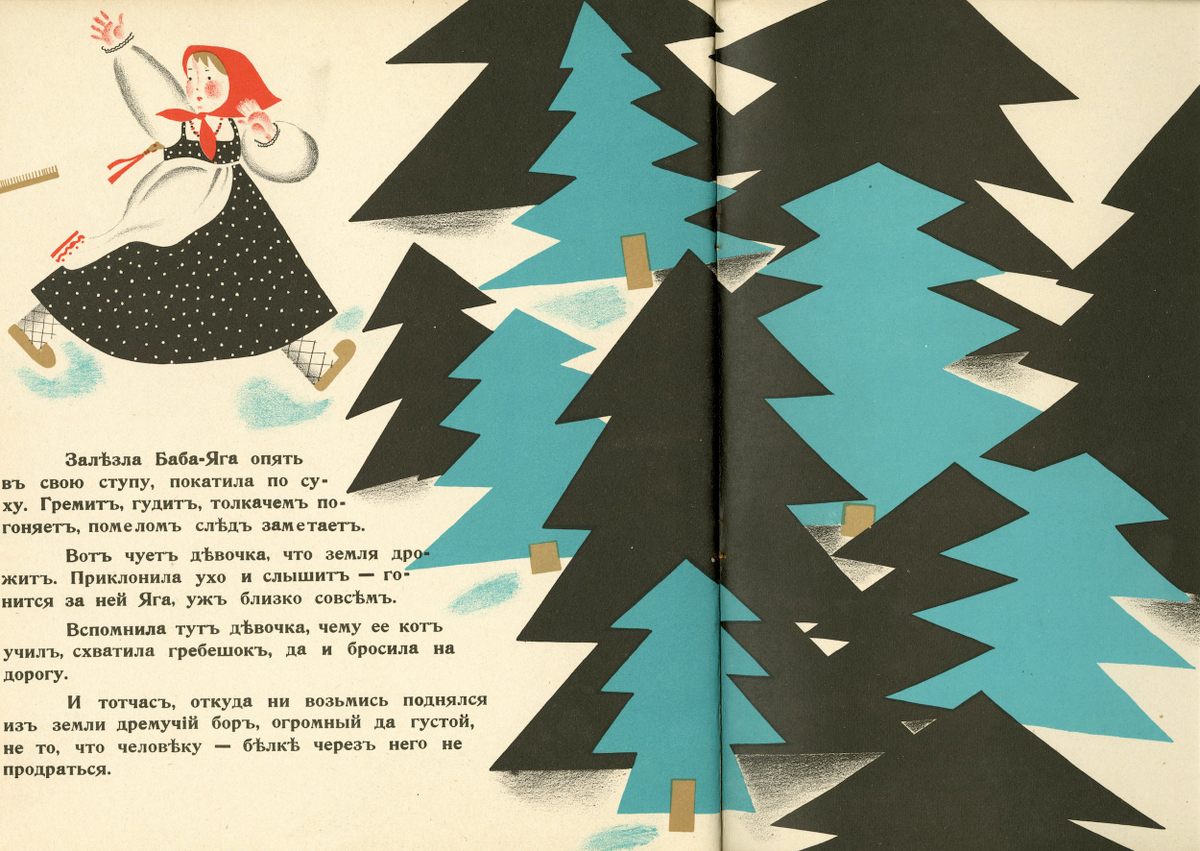

When she started to illustrate children’s books, she used all the hallmarks of the school—simple geometric shapes, cutouts, collages, simplified palettes. In her 1932 Baba-Yaga, the forest is made of simplified pine trees in blue and black, which seem to pop from the page. The cover features six girls wearing headscarves and aprons in red, white, and brown, and forming a simple circle.

When Christine Jacobson, the assistant curator of modern books and manuscripts at Harvard’s Houghton Library, saw the cover, it surprised her.

“It’s a very avant-garde cover,” she says. In the 1920s and 1930s, a golden age of Soviet children’s literature, that wasn’t uncommon: Some of the most cutting-edge art could be found in children’s books. But this book told a classic Russian folktale, in which a young girl encounters the witchy Baba Yaga and her walking house. That should have been off-limits. “You have anthropomorphic flora and fauna, magic, evil step-mothers—you have all these things you’re not supposed to have in Soviet children’s work,” Jacobson says.

Most often, the story told about early Soviet kids’ books focuses on their political aims, as propaganda that aimed to inculcate young minds with revolutionary ideas. But part of Jacobson’s job is to help expand the library’s collection with an eye to preserving and elevating works that might have been overlooked because they weren’t made by Western Europeans, or by men. She recently acquired Baba-Yaga, as well as another unusual work from Soviet children’s literature, From Moscow to Bukhara.

These books, which marry older threads of Russian culture with Soviet and avant-garde ideas, don’t exactly fit the dominant narrative about Soviet kids’ books. But preserving the work of the perhaps overlooked women behind these books adds new color and depth to the idea that Soviet children’s book were a perfect marriage of propaganda and art.

“What I liked about these two books was that they were by people I had never heard of,” Jacobson says. “They were by women. And they seemed to be breaking a lot of rules of early Soviet children’s books.”

In the early years of the Soviet Union, authors and illustrators invigorated by the revolutionary spirit reimagined children’s literature, and set to work at the centuries-old task of shaping young minds through simple stories and vivid pictures. In one iconic poster, Lenin has his arms outstretched, imploring the country to “Give Us the New Children’s Book.” Baba Yaga, demons, kings, and queens were out, and planes, parades, and farming were in. These new children’s books leaned on abstract, avant-garde images and are easily identified—just like the iconic Soviet posters—as the products of a particular place, time, and ideology.

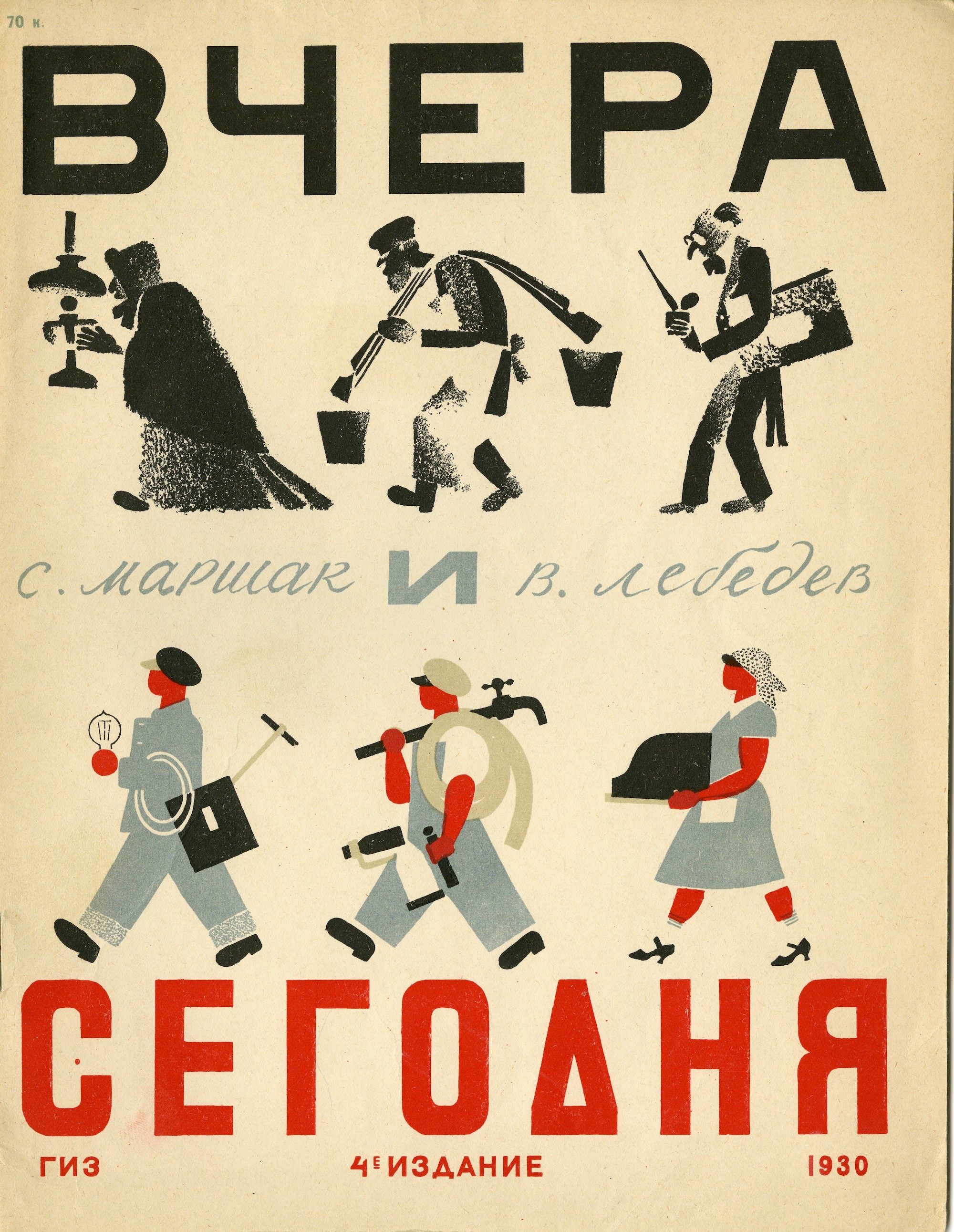

Although the revolution created new opportunities for women, children’s books were still written and illustrated mostly by men. In a short period of time, artists and authors—most famously, the team of Vladimir Lebedev and Samuil Marshak—carved out a space for creativity and innovation, during a time of “uneasy equilibrium of politics and art,” as Sara Pankenier Weld, a Slavic literature scholar at the University of California, Santa Barbara, writes in her work on Russian avant-garde picture-books.

But this was only a brief window, before the pressure of propaganda took over. “Any women who joined avant-garde children’s book illustration after it had been established … would have had little time to make a unique contribution before this window closed,” writes Weld.

But the books that the Houghton Library uncovered reveal other cul-de-sacs in the story of Soviet children’s books. Chelpanova married a French philosopher and became Nathalie Parain. She moved to France, where she socialized with some of the time’s most influential avant-garde Russian artists. Because her work was published in Paris, she would have been freer than artists back home to choose her subjects. Like other Russian illustrators, she chose avant-garde images to match with her stories. But she ignored Lenin’s dictum and applied that aesthetic to a classic tale, hinting at how the nation’s past might connect to its present.

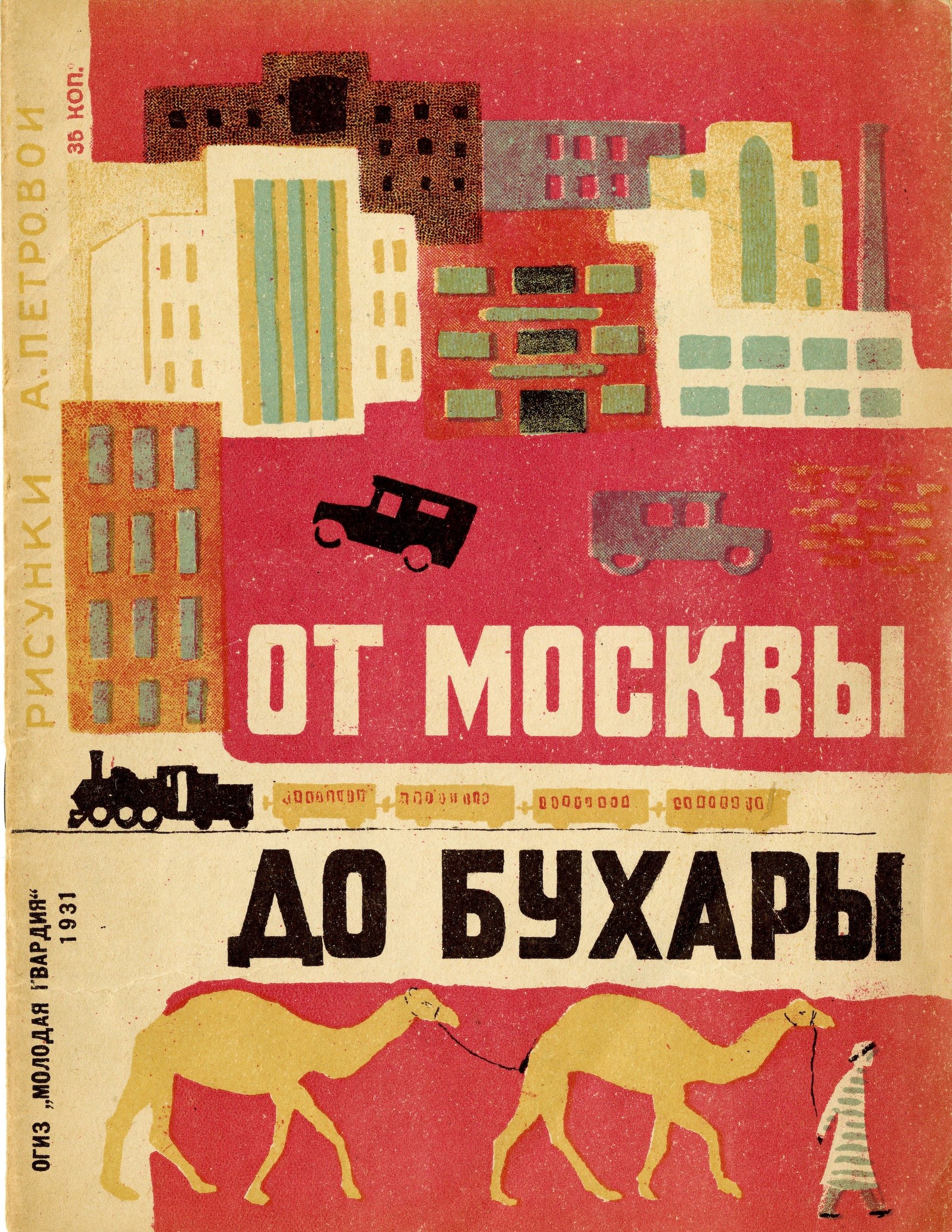

The author of From Moscow to Bukhara, Aleksandra Petrova had a different story. “She’s not of the avant-garde. She’s of the approved artist milieu of the time,” says Jacobson. Petrova was hired to paint murals in a Moscow subway station, for instance, which she executed in the style of Soviet realism.

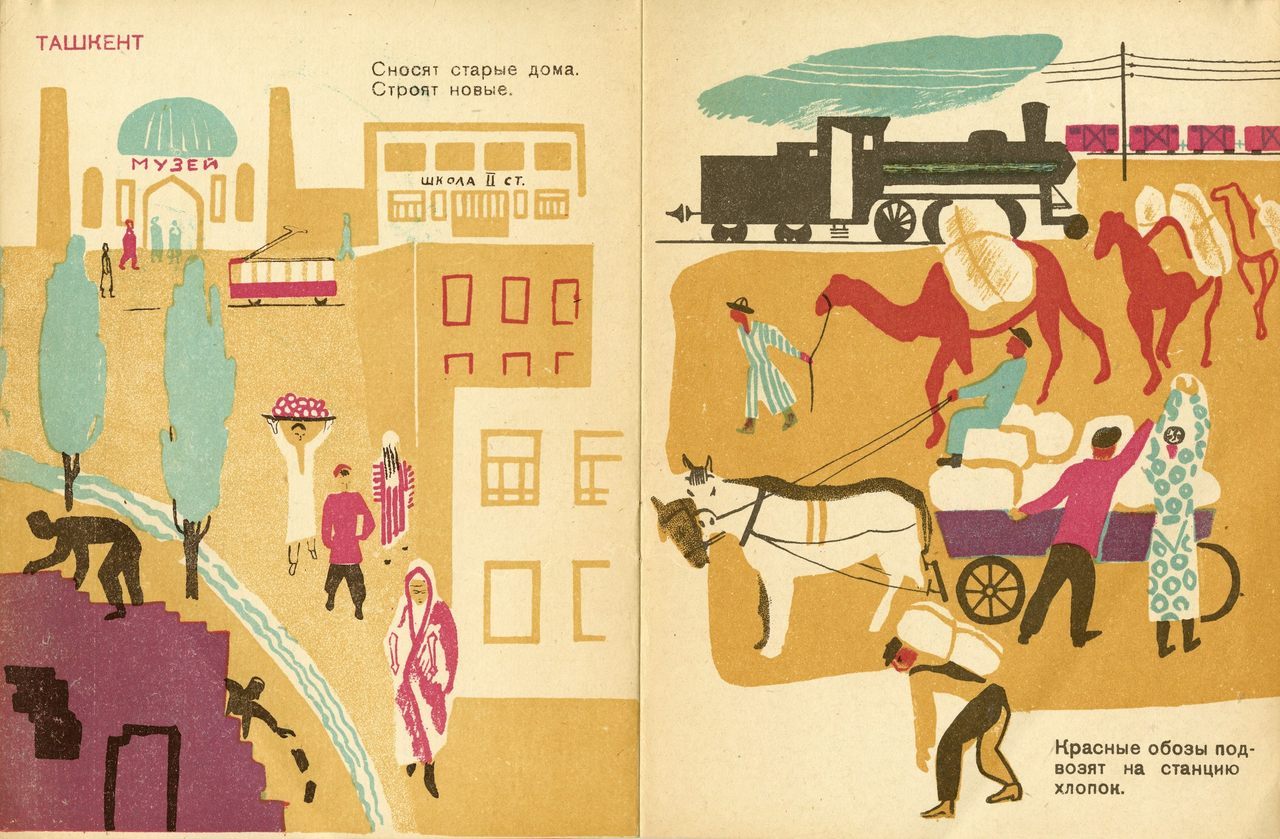

But in her children’s book, Petrova took a leap. She borrowed from avant-garde artists in her illustrations, using limited colors and bold, simplified figures. But in her choice of topics she, too, drifted from the rules of the new Soviet children’s books. Most avant-garde children’s books showed figures against blank space: The future hadn’t been filled in yet. And many of the books avoided showing scenes of daily life, since reality didn’t always stack up to the perfect world promised by communist ideology. But Petrova took a risk and showed scenes of traditional Uzbek life to show how Soviet influence had transformed it. Her illustrations depict schools, trains, and a mosque with a “museum” sign on it, and although it’s not overtly anti-revolutionary, the book reveals the ways in which the Soviet Union still treated parts of its domain with a colonial instinct.

“The more you dig into Soviet children’s literature the more you find outliers doing really interesting things and breaking the rules,” Jacobson says. Often, Soviet Russia is understood as a monolith, with the state controlling all human endeavor. There’s truth to that view. It wasn’t long before even Marshak and Lebedev, one of the most celebrated teams in this realm, came under pressure to rein in their most bold and creative impulses. But history and people are complicated. And that’s part of a library’s job—to find and save cultural treasures that can help tell a fuller story of how people thought and expressed themselves in the past.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook