The First Asteroid We Knew Would Hit Earth in Advance

When 2008-TC3 crashed into the Sudanese desert, not everyone was surprised.

On October 7, 2008, at quarter-to-six in the morning, commuters waiting for the train at Station 6 in Nubia, Sudan, were greeted to a spectacular display: a massive fireball that streaked through the sky overhead and quickly disappeared.

It seems safe to say that they were surprised. Elsewhere in the world, though, astronomers had been expecting it. This was 2008-TC3—the first asteroid scientists had ever spotted in time to predict its arrival, a feat that hasn’t been repeated since.

“It’s the only case where an object was discovered in space, before it struck the earth,” says Richard Binzel, an asteroid expert and a professor of planetary sciences at MIT. Although Binzel was not directly involved with the effort to track 2008-TC3, he watched it play out in real time, along with much of the rest of the international astronomy community.

As Emily Lakdawalla of the Planetary Society reported soon afterward, it all started on October 6, about twenty minutes before midnight, when the University of Arizona researcher Richard Kowalski “discovered an object… that appeared to be on a collision course with Earth.” The object, then called 8TA9D69, was soon spotted by other observatories in Arizona and Australia. They all called in reports to the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center, a NASA-funded group that’s in charge of keeping track of the various B-list rocks whirling around our solar system.

-f37b7733-06f3-420a-9831-9cc19ec1fef5.webp)

The MPC gave the asteroid a more formal, and slightly catchier, name: 2008-TC3. They then set out to get its story straight, and to tell everyone about it. The asteroid was 88 tons, about as heavy as a blue whale, and had a 13-foot diameter, the same as a large trampoline. It posed no danger to Earthlings, as it would almost certainly not survive its passage through the atmosphere.

The next eleven hours was a game of long-distance cat and mouse. “Astronomers around the world scrambled to their telescopes,” Lakdawalla wrote. Those who successfully spotted the asteroid submitted their observations to the MPC, which continued to refine its orbit, and thus to tighten predictions about exactly where and when it would hit.

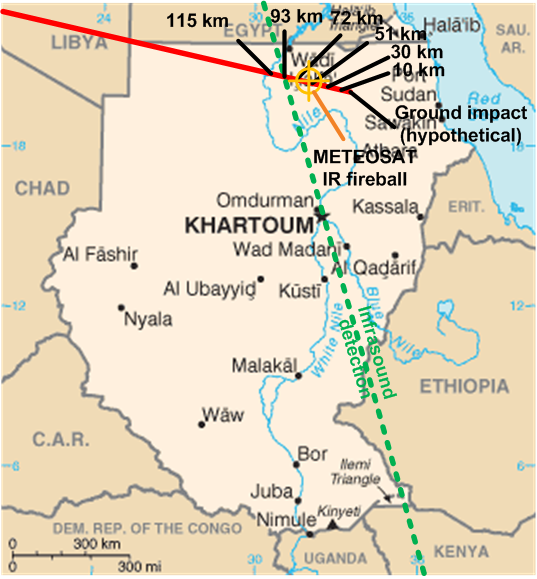

Eventually, they made the final call: it was heading for the Nubian Desert in Sudan, and would enter the atmosphere there at 5:45:28 a.m. local time, give or take fifteen seconds. Different scientists kept an eye on it until 4:40 a.m. Sudan time, at which point the asteroid disappeared into Earth’s shadow. Its last hour of approach was shrouded in darkness.

At that point, everyone who had been watching the asteroid hunkered down and waited for it to get here. The Center for Astrophysics put out a press release about the new arrival—which, they wrote, would appear as “an extremely bright fireball traveling rapidly across the sky.” The United States also tried to give Sudan a heads up: “There was an attempt to call the embassy in Sudan and say that this event is going to happen,” says Binzel. “But it was the middle of the night, and no one answered the phone.” One meteorologist, Jacob Kuiper, dialed Air France, and suggested they radio their nearby pilots so that they could keep an eye out.

The impact time came and went. Now, the astronomers faced another needle-in-haystack problem: how to figure out whether their predictions had come true. Satellite images helped them pinpoint the impact spot. An earthquake detector in Kenya picked up the blast the asteroid made as it came through the atmosphere, which verified the time.

Eyewitness reports came in from the people at the train station, as well as one Air France pilot who had been flying over Chad. And although they didn’t expect to find any physical traces—it was thought the asteroid would vaporize completely—a team of students and staff from the University of Khartoum went out to search the desert for space rocks.

Sure enough, they ended up discovering 15 meteorites—pebble-sized, jet-black, and “fresh-looking,” as the resulting scientific paper put it. Follow-up trips increased the total haul to 280. These were the first rocks ever discovered that could be directly linked to a particular asteroid observed in space, and subsequent analysis of them has helped scientists begin to trace where asteroids come from.

Thanks to real-time international teamwork, astronomers had been able to turn Kowalski’s single initial observation into a kind of scientific comet-streak: a 12-hour rush of useful predictions, followed by a long, elegant tail of unique discoveries. Overall, NASA later declared, “the system worked well for the first predicted impact by a near-Earth object.”

Encouraging—especially since it will definitely not be the last. “A house-sized object flies in between the earth and the moon at least weekly,” says Binzel. “The objects are going to be there no mater what, it’s just a question of whether we see them in advance.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook