Why Are So Many Horror Movies Set at Summer Camp?

Isolation and a heady mix of hormones and fear provide the perfect setting for bloody revenge.

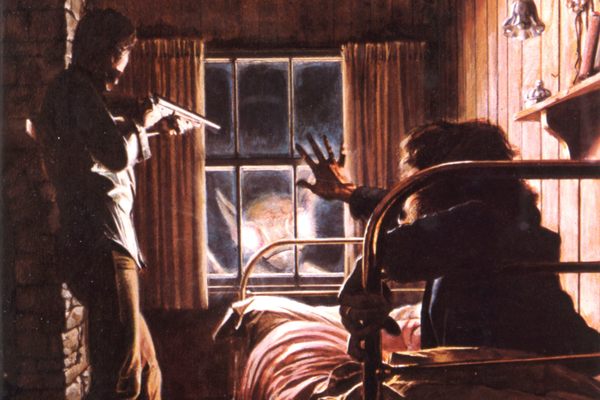

In the attic of a rural cabin, two teenagers are making out. As things get hot and heavy, the camera tracks them with a voyeuristic gaze. Suddenly the young couple spring apart, caught in the act by an unseen interloper. Then the knife comes out, delivering the classic slasher movie punishment for sex. A minute later, both kids are dead.

Even if you haven’t seen it, this scene likely sounds familiar—as will the overall gist of Friday the 13th, which involves a group of summer camp counselors being picked off by a mysterious killer.

It’s a classic of the American slasher formula, a genre that took off after the demise of Hays Code censorship in 1968. Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Black Christmas both arrived in 1974, with John Carpenter’s Halloween coming out in 1978. Thanks to Friday the 13th (1980), summer camps became a popular recurring location.

Of course, popularity doesn’t necessarily denote artistic merit. The 1980s slasher movies were frequently accused of being exploitative and misogynistic, with contemporary reviews labeling Friday the 13th “shamelessly bad” and “nauseating.” Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert singled it out as a notably unpleasant example of the genre. However that didn’t stop the masked killer Jason Voorhees from becoming a Hollywood juggernaut, slicing and dicing his way through 11 sequels. Meanwhile other filmmakers released a slew of copycats (Madman, The Burning, Sleepaway Camp, Twisted Nightmare…), enthusiastically butchering a generation of fictional campers. As it turned out, summer camp embodied a perfect combination of ingredients for slasher cinema.

First off, there’s the secluded setting. “You want that isolation, you want your characters separated from mainstream society,” explains film critic John Kenneth Muir, author of Horror Films of the 1980s.

Crucially though, sleepaway camps aren’t too secluded. They’re close enough to civilization that the characters can seek help from what Muir calls a “useless authority”—an incompetent cop or feckless boss who ultimately leaves the heroes to fend for themselves.

Campfire stories provide a built-in expository device to introduce the villain, and the camp counselors supply a ready-made cast of scantily-clad young victims. And as Muir points out, the location is littered with convenient weapons. “You’ve got the archery contest… You have things like canoes and oars to separate people even further from the center of the action.”

Above all, summer camp is relatable. Like the suburban babysitter premise of Halloween, movies like Sleepaway Camp transformed a bastion of middle class normalcy into a thrilling gorefest. Representing many Americans’ first taste of life without parental supervision, summer camp offered an accessible combination of familiarity and fear.

According to historian Leslie Paris, author of Children’s Nature: The Rise of the American Summer Camp, the first sleepaway camps appeared in the late 19th century. Initially they were a male-only phenomenon, overlapping with the tenets of Muscular Christianity, which associated masculinity and fitness with spiritual purity. These early camps tackled a growing concern that elite boys were growing soft in cities like New York and Boston, and “an experience of rugged outdoor adventure” would whip them into shape. Over the next few decades, camps began catering to a wider range of demographics, introducing city kids to nature in a controlled environment.

“For many kids of this earlier period, just going away from home could be kind of scary,” explains Paris. So there’s a long history of summer camp being associated with childhood fear, whether that involved practical concerns about wild animals and dark forests, or the tradition of telling spooky stories around the fire.

Campfire tales inevitably fed into the summer camp horror genre, often drawing from dubious Native American folklore or rumors about fictitious murderers like the Hookman. “These stories had multiple purposes,” says Paris. “One was to build community and entertain the campers. But another may have been to make sure the kids didn’t wander off into the woods on their own at night.”

With all that cultural backstory in place, it’s no surprise that summer camp horror movies took off. The real question is why this happened in the 1980s, and not before. Even prior to the slasher era, summer camp should’ve been a shoo-in for other types of horror. Instead, earlier summer camp movies mostly focused on comedy and romance.

Paris suggests that this reflected a shift in public attitudes, as the perception of summer camp shifted from wholesome outdoor fun to something more “jaundiced.” John Kenneth Muir, meanwhile, sees summer camp horror as a product of the Reagan era, representing “a reassertion of conservative values” and “Old Testament draconian beliefs.”

“The paradigm of these films is really ‘vice precedes slice and dice,’” Muir notes, highlighting summer camp’s reputation as a place of sexual awakening. It makes sense for these teen characters to hook up and smoke weed, but as soon as they do, “they’re almost instantly punished by the boogieman.”

Adding to the Old Testament undertones, these films often link their villains with the perils of nature. Muir argues that Friday the 13th is more sophisticated than its legacy suggests, introducing a world of “Norman Rockwell Americana” that’s interrupted by a snake in the first act, establishing the idea of an unseen threat in this adolescent garden of Eden. When a thunderstorm takes out the lights, “it’s almost like God is abetting these killers to get these sinning teenagers.”

This blend of conservatism and exploitation drew criticism at the time, overlapping with complaints about gratuitous nudity and violence. However 1980s slashers also cemented the “final girl” archetype: a female lead who defeats the villain through her own ingenuity. Later films used this as a springboard for more overtly feminist storytelling, and franchises like Scream and Halloween have evolved to reflect 21st century values.

Weirdly though, the summer camp genre hasn’t experienced a similar revitalization. Most recent examples are pretty obscure, overshadowed by A-list remixes of other classic tropes like evil nuns, rural ax-murderers and campus killers. There’s also a suggestion that summer camp belongs in the past, with films like The Final Girls (2015) and Fear Street 1978 (2021) embracing nostalgia in a vintage setting.

So what happened to summer camp horror? This may sound like sacrilege to some, but perhaps we exhausted the genre back in the ‘80s. Even Friday the 13th didn’t stick around for long, with later sequels transporting Jason to New York, and then to outer space, and to Hell. Teenage campers could only sustain him for so long.

Another possible explanation is that summer camp no longer feels inherently scary. Leaving home for a few weeks just isn’t a big deal, and sleepaway camp has gone back to seeming quaint and childish. Young people in 2024 have different things to fear.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook