Is There Sunken Treasure Beneath the Treacherous Currents of Hell Gate?

In the heart of New York City, a centuries-long hunt for Revolutionary War–Era gold.

Just off the coast of Astoria, Queens, at the confluence of the Harlem and East Rivers, is a narrow tidal channel. Hell Gate. Its fast currents change multiple times a day and it used to be riddled with rocks just beneath the surface. Even today, visitors to Randall’s Island Park can see the swirling churn and watch pleasure boaters struggle through. American author Washington Irving wrote an essay about it: “Woe to the unlucky vessel that ventures into its clutches.”

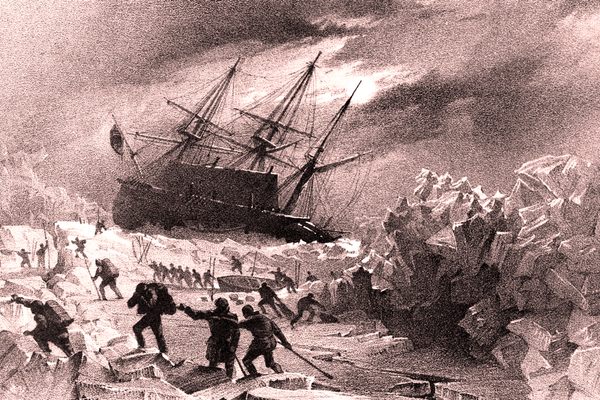

But many a vessel did venture into those clutches over the centuries. Traversing it could save sailors navigating between New York Harbor and Southern New England days of travel around Long Island. This expediency often came at a cost. Hell Gate is the final resting place of literally hundreds of ships. Most of them are forgotten but one continues to captivate. Because down there, under the minor maelstroms, is the promise of gold.

The East River runs up from New York Harbor with Manhattan on one side and first Brooklyn then Queens on the other. At Randall’s Island it splits. To the west, it becomes the Harlem River, which skirts around the top of Manhattan to join the Hudson. In the other direction, it connects to the entirety of Long Island Sound—but it’s easy to miss that this connection comes only via a single, slim channel. Each time the tide turns, the Atlantic forces its way through this passage in one direction or the other, with the discharge of the Harlem River adding to the chaos.

“Because those volumes are large, and the opening at Hell Gate is small, it means the velocity is going to get very high and that makes it difficult to navigate,” says Roy Messaros, a coastal engineer and professor of hydraulics at New York University.

“Even on a calm day the current is boiling,” says John Lipscomb, who regularly patrols New York Harbor on a 36-foot wooden boat for the environmental nonprofit Riverkeeper. “It’s a boisterous place. There are whirlpools and the wind against the tide causes interesting, short, aggressive waves. You pay attention when you’re in Hell Gate.”

That’s today. Conditions in the past were even worse. Most rocks in the area have now been removed to facilitate navigation, but Hell Gate used to be a minefield. It sounded like Hell, too. The whirlpools could be heard from “a quarter of an hour’s distance,” according to one 17th-century Dutch traveler. During the 1850s, it was estimated that about one in 50 ships that crossed Hell Gate was either damaged or sunk.

“You’re talking about centuries of navigation,” says Bronx Borough Historian Lloyd Ultan. “Everything from rowboats to large ships have been sunk by hitting those rocks. One on top of the other on top of the other on top of the other.”

Out of all those wrecks, one in particular has obsessed people for over 240 years—HMS Hussar. The whole gamut of underwater exploration technology has been employed in the search for its purported treasure, from 18th-century diving bells to modern sonar scanners. The cast of characters who have invested significant time and money into salvaging the ship is equally wide-ranging. Thomas Jefferson had a go, as did the inventor of the modern submarine. Alongside crews of schemers and hustlers, serious underwater archaeologists have tried, too. Most recently the most prominent attempts to find the wreck were the brainchild of a Bronx man who calls himself Joey Treasures.

The coveted ship was a frigate of the Royal Navy that arrived in British-occupied New York during the Revolutionary War, in November 1780, reportedly carrying the payroll of British troops in gold coins. Shortly after arriving in the city, Hussar set sail for Gardiner’s Bay on the eastern end of Long Island (though some accounts say it was headed to Newport, Rhode Island). While traversing Hell Gate it hit a submerged formation known as Pot Rock and began taking on water. The ship drifted down the East River until it sank to a depth of 60 to 80 feet, somewhere off the coast of the Bronx. This much is known. The rest, much like the waters of Hell Gate, is murky.

Accounts differ on how many, if any, of the crew were lost, but most agree that around 60 American prisoners of war who were shackled below deck went down with the ship. Crucially, whether Hussar still had gold on board when it sank has also been the subject of much debate over the past two centuries. Modern historians tend to think not. Contemporaneous news articles about the accident made no mention of treasure, nor do the minutes from the Royal Navy court martial into the loss of the frigate.

“It’s a pie-in-the-sky romantic notion that you could find gold in the waters of the Bronx,” says Ultan. But this did not stop generations of people from trying, beginning in the early 19th century. It was known that the ship was carrying gold when it arrived in New York, and in the decades after Hussar sank, “the legend began to grow that the gold was still on the ship,” says Ultan. “The East River at the southeastern end of the Bronx suddenly becomes the Spanish Main.”

By the 1810s, the notion that a fortune in gold was lying near the bottom of Hell Gate had become an almost-uncontested truth in the New York press, and would remain so well into the 20th century. “You have to remember it’s a good story,” says Ultan. “It sells copy.” This frenzy may have been initially fed by the British themselves, who, despite denying that there was gold in Hussar when it sank, sent over a team of experts to salvage the ship in the 1790s, “with results wholly ineffectual,” according to a New York Times article from several decades later.

Press speculation on the value of the gold varied wildly. The “large amount” vaguely referred to in early articles suddenly became the oddly specific sum of £600,000, and then $1,000,000, then $5,000,000. In the 1980s, an international coin dealer told The New York Times that the bullion said to be in the Hussar wreck could fetch a whopping half a billion dollars in the rare coins market. “Everything gets distorted,” says Ultan. “It’s like a game of telephone.”

Early attempts to salvage the ship, including by the British, involved diving bells, a technology that dates back to antiquity and is still used today. Divers descended in a small metal chamber with an open bottom, with the air pocket that allowed them to breathe at depth as they more or less felt around the bottom. At and around Hell Gate, this yielded few results. Diving was only possible for short windows, and even then the currents would toss the bell around, making any kind of concerted search impossible.

In 1811, a salvage company partially funded by Thomas Jefferson managed to bring up iron nails and copper, which amounted to a “considerable sum,” according to an article in the New York Evening Post from that year. They also raised a barrel of butter, value unknown, but alas, no gold.

Where one might see failure, another might see opportunity. A man from Baltimore named Samuel Davis thought he would have a go at raising the entire vessel. He began publishing ads in newspapers throughout the Northeast in 1819, seeking funds to build a machine capable of the feat.

In his ads, Davis provided a statement from a man who claimed his father had witnessed gold being loaded into Hussar. Another oft-quoted anecdote involved the widow of Hussar’s pilot, who was still living in New York and had frequently heard her late husband say that there was a “large quantity of money aboard the ship when she sunk,” according to an 1823 article in the New York Evening Post.

Fundraising schemes like this, where shares of a potential treasure are sold to investors, have long been common in the salvage industry, even today. “Treasure hunting operations are often scams,” says author Jerry Kuntz, who wrote a book on 19th-century salvagers, The Heroic Age of Diving. “The size of the treasure is often exaggerated. The evidence for the treasure is often falsified. It’s a murky business, has been for centuries and continues to be so to this day.”

Evidently the enticements—and, as always, the promise of gold—lured enough investors to Davis’s enterprise. His crowd-funded machine operated like a massive claw, with each side supported by an adjacent ship. One journalist described it as a set of “huge iron tongs.” By 1823 it had been built and was ready to be put to work in Hell Gate. What happened next is not entirely clear. There is no account from the time of how Davis’s invention fared, or how satisfied his investors were with the results. A New Yorker article from over a century later would say that Davis managed to raise part of Hussar’s stern above water. “At that point the cables broke and he gave up the effort,” it read.

As underwater technology evolved, so did the search for Hussar. George W. Taylor, a pioneer of American diving, was the first to explore the wreck in a diving suit in 1843, but his ill health and premature death a few years later meant he never completed his investigation. In his deathbed, he urged his protégé, Charles Pratt, to keep searching for the lost gold. Pratt returned to Hell Gate every summer for over a decade.

He was arguably more successful than any of his predecessors. The suit, which was officially patented as “submarine armor,” afforded divers a level of mobility that previous salvagers, constrained by diving bells, could have only dreamed of. “They could range around more, see through the ports of the helmet and pick up objects and use tools,” says Kuntz. “It revolutionized the work of salvagers.” It also helped that Pratt was highly skilled at his craft and probably the most experienced American diver of his time.

But even for him the waters around Hell Gate were a worthy opponent. The bottom lived up to the tempestuous reputation of its surface waters. Currents remained fierce, visibility was near-nonexistent, and the submarine armor was cumbersome. It was made of a combination of rubber and metal and weighed around 70 pounds. Its copper helmet had to be bolted to the diver’s neck piece. A rubber hose connected the helmet to a hand-cranked air pump at the surface.

Over the course of 13 years, Pratt salvaged numerous artifacts from Hussar. He raised cannons and cannonballs, bottles of wine and swords. He found human bones still in shackles—likely the remains of the American prisoners. Tantalizingly, he also found several 18th-century gold guineas, but far from the promised windfall. The coins probably belonged to the crew and were not a part of a larger haul, but were more than enough to keep the legend alive. Like others before him, Pratt had difficulty breaching the wreck’s lower deck, where cargo was traditionally stored. He dove on Hussar for the last time in 1866. (Fast forward to 2013, when Central Park Conservancy employees were cleaning a cannon from Hussar that had likely been donated by Pratt and kept in storage for many years. They were surprised to discover it was still loaded with gunpowder and a cannonball. The NYPD bomb squad was called on to diffuse it.)

Several salvage companies worked on Hussar over the ensuing decades, without Pratt’s success. One notable attempt was led by a less-than-reputable street preacher named George W. Thomas, who, like Davis before him, convinced investors to back his effort. They gave him $70,000, roughly equivalent to $2 million today, though he was later accused of using the money to buy a lavish house in New Jersey. In 1900, divers trying to salvage a yacht in the East River found an anchor with “H.M.S. Hussar” inscribed on it and sold it to a junk shop. After a century of regular media coverage, it would be almost 40 years until Hussar made headlines again.

Four decades is a long time in a place like Hell Gate. Somewhere along the way, the location of the wreck was lost. Hell Gate itself had changed significantly over the course of the 19th century. Its rocks had been blown to bits to facilitate boat traffic, first by a French civil engineer in the 1850s and later by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Pot Rock, the hazard that sank Hussar, was the first to go. The greatest of these blasts happened in 1885, when 300,000 pounds of explosives were simultaneously set off in the waters of Hell Gate, lifting a geyser of foam and rock high in the air. Journalists at the time hyped it as the single largest explosion in history. The blast was felt as far as Princeton, New Jersey, 50 miles away, according to the New York City Parks Department website entry for Mill Rock Island, where the explosives were prepped. One can only imagine the effect that this blast and the ones that came before it, all over Hell Gate, had on the remains of the wrecks below.

But even after dozens of failed attempts and the bombardment, there were still those who believed there was a fortune waiting to be discovered. Simon Lake, one of the inventors of the modern submarine, began looking for Hussar in 1935 in a “baby-submarine” of his own creation, adapted to the conditions of the East River. A year later he gathered journalists in his hotel room and announced that he had found the ship. “Within six weeks I expect to step within her hold,” he told The New York Times. This never came to pass. Whatever Lake had found, it was not Hussar. He ended the 1930s in dire financial straits.

Fifty years later, another underwater explorer would continue the search. Salvage expert Barry Clifford came to the project with a pedigree. He had just discovered Samuel Bellamy’s treasure-filled pirate ship, Wydah, off the coast of Cape Cod. Hussar seemed like the next logical step. Clifford and his team began taking sonar images of the bottom of Hell Gate in 1985. The same technology had just been used to locate the wreck of Titanic that same year. Within months, in an echo of Simon Lake’s hotel room press conference, Clifford announced to the world that he had found the wreck. “My opinion is there is a very strong possibility that there is treasure on board the Hussar,” he told The New York Times. But when divers got in the water it was a different story. In the end, Clifford and his team encountered abandoned cars, washing machines and seven other shipwrecks, but none from the Revolutionary War era.

And with that, the era of serious salvagers and underwater explorers was deep-sixed. The latest to take up the mantle left by others before is an actor and demolition worker from the Bronx named Joe Governali, who goes by “Joey Treasures.” Governali has been trying to secure exclusive salvage rights over the wreck since the early 2000s. In a deposition, Governali claimed to have found an old map in the Rare Books Room of the New York Public Library that revealed the location of the ship. His salvage company conducted several exploratory dives, but have little to show for it other than some grainy video of what Governali claims is the wreck of Hussar and an 18th-century beer pitcher of British origin. Governali produced a reality TV pilot of his escapades. Alas, he is also being accused of fraud by one of his investors, James Kays, who was convinced to pitch in $100,000 after being shown gold coins purported to be from Hussar. According to court records, they were allegedly “junk bought on eBay.”

It’s difficult to predict what the next phase of this centuries-long treasure hunt will be, but it’s likely to continue in some form. James Kays’s lawyer wrote in a letter to the judge presiding over the case that his client intends to continue the search, just as soon as he gets his money back.

The next big development might be with Hell Gate itself. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has proposed major civil works in the area to protect New York City from storm surges. Some versions of the proposal include large storm barriers that could permanently alter the tidal exchange between the East River, Long Island Sound, and New York Harbor, potentially weakening Hell Gate’s infamous currents. Although such barriers would only close during rare storms, they “threaten to choke off the tidal flow” even when open, according to Riverkeeper. The Army Corps of Engineers indicated recently that they are leaning towards a less invasive alternative but the storm barriers have not yet been ruled out. “It remains possible that other alternatives or components of those alternatives may also be advanced,” according to New York/New Jersey Harbor and Tributaries Project Manager Bryce Wisemiller.

For now at least, the currents of Hell Gate will keep on flowing unobstructed. As for Hussar, the promise of its gold remains alive and well, even if the same may not be true for the ship itself. After two centuries of salt corrosion, violent tides, salvage attempts and maybe explosives, it’s a safe bet that whatever remains of it is probably beyond recognition. “I think the Hussar is hither and yon,” says Lloyd Ultan. “It’s a little bit here, a little bit there, a little bit everywhere.”

In his essay about Hell Gate, Washington Irving mentions how he had grown up hearing fantastic stories about the remains of a ship that lay scattered among the channel’s rocks, one of the many that fell victim to its currents. As an adult, he tried to find the truth about those stories. “I found infinite difficulty, however, in arriving at any precise information,” he wrote. “In seeking to dig up one fact it is incredible the number of fables which I unearthed.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook