This Tiny Volcanic Island Is the Ultimate Natural Laboratory

Only careful, highly trained scientists ever set foot on Iceland’s Surtsey.

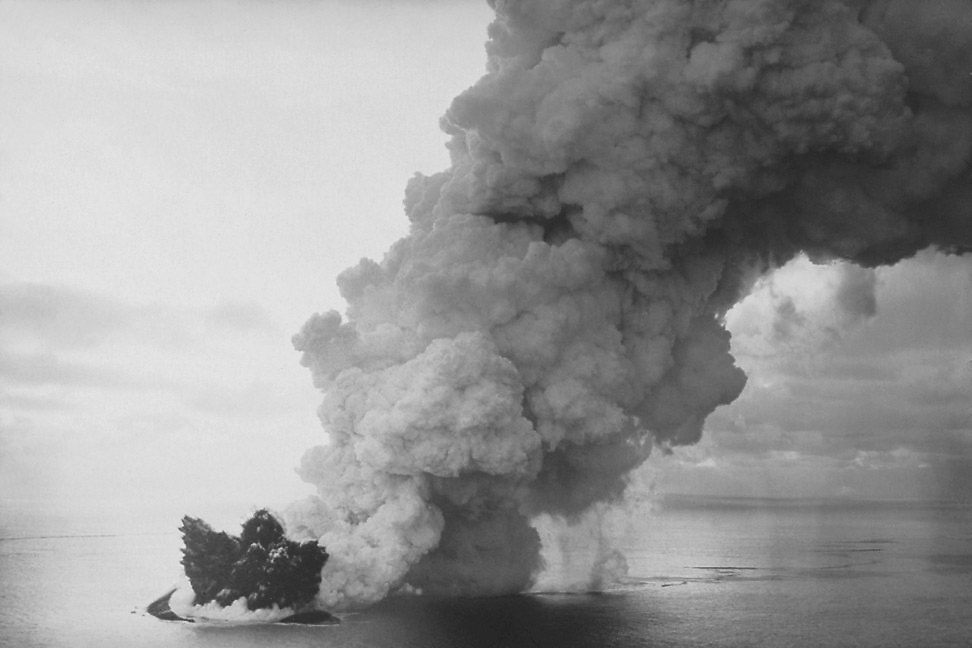

A plume of steam and ash burst suddenly from the North Atlantic Ocean on November 14, 1963, and for the next three-and-a-half years, a series of eruptions produced a new island of basalt and ash about 20 miles from Icelands’s southern coast. The new speck of land was dubbed Surtsey Island, after a black fire giant of Norse mythology. Today, it’s one of the few places on Earth that has remained relatively pristine and untouched by humans.

Early on, scientists recognized that Surtsey offered a unique opportunity to observe the infancy of a new volcanic island. What would be the first life to arrive, and how would it get there? How would the rock change as the ocean beat against its shores? Iceland’s government declared the island off-limits to anyone but just a few researchers granted permission to study the evolution of Surtsey.

Even today, researchers must get government approval before venturing to Surtsey and once they are on the island, must follow strict rules to avoid contaminating it with seeds or chemicals. A drilling expedition earlier this year perfectly illustrates the lengths to which scientists must go. “We went to enormous efforts to protect the island from any sort of contamination at all,” says Marie Jackson, a geologist at the University of Utah and one of the leaders of the expedition.

All the equipment was brought to the island in pieces by boat or helicopter—more than 90 helicopter lifts for the drilling setup alone—and then assembled on the island. The researchers went to great lengths to avoid fuel spills, and had to dig out the drilling site by hand. Every meal was prepared in advance, and included an extra two week’s supply, in case weather prevented them from leaving the island on schedule. The scientists and technical staff were all trained on how to avoid bringing new plants or animals to Surtsey, which includes checking clothing and other gear for hitchhikers such as seeds. They also had to stick to established paths and couldn’t explore other areas of the half-square-mile island. And once they had collected the core samples they came for, says Jackson, “literally everything we did, we took off the island.” That included their waste.

Trips to Surtsey also have to be timed to avoid disturbing the animals that have taken up residence. Jackson’s expedition was right after nesting season for some of the island’s birds had ended in July, and they had to wrap up before seals and their young came to live on Surtsey for the season in September. Visiting scientists must collect data and samples, and then do their analyses elsewhere. Jackson’s team took their cores to nearby Heimaey Island to image and analyze rock samples.

All that careful planning has been worth it—Surtsey remains pristine, and still allows scientists to learn about how life establishes itself on a new island, how a new ecological community evolves, and even how life affects geologic processes.

Life came to Surtsey within a year of its birth. A 1964 New York Times article notes that plants, birds, and even a mosquito had already shown up. Spiders were blown to the island, while some other insects arrived by floating across the ocean’s surface. Perhaps expectedly, birds were some of the first inhabitants of Surtsey, and a number of species have been spotted since, including some squacco herons typically only seen in Southern Europe.

Recent research has focused on smaller residents. Jackson’s expedition was drilling cores from Surtsey’s interior to look for signs of microbial life in the young basalt, which could help scientists understand an important geologic process. Basalt is one of the oldest types of rocks on Earth, and its creation “is a process that has been going on in the Earth’s crust for billions of years,” says Jackson. “But we know very little about the first things that happen in freshly erupted basalt on the seafloor. Surtsey is giving us a window to study this.”

Drilling on the seafloor is a complex process, and bringing up samples of rock that aren’t contaminated by ocean water—and all the microbes it contains—is near impossible. The eruptions that created Surtsey, on the other hand, brought freshly erupted basalt to a much more accessible place. “Surtsey gives us a very different platform—we can put the drill on real land,” says Jackson. This gives them more control over the drilling process, which can include a sterilized system to preserve the microbes. Such microbes are capable of changing the chemical composition of rocks, and even their magnetic properties. “It’s a unique opportunity to look at the very, very beginning of these processes,” she says.

The cores might also help researchers understand why Surtsey looks the way it does. “Surtsey is very, very young,” says Jackson. “It’s a fraction of a second in geologic time. But on the surface, it looks very old.” Erosion has shaped Surtsey’s surface. Lava flows are breaking apart to form boulders, for example. The constant battering of the ocean has shaped the shoreline, too, shrinking the island by about 50 percent. “We’re trying to understand what processes are contributing to this accelerated aging.”

Surtsey was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2008, which adds another layer of official protection to help keep the island pristine. And for the foreseeable future, the only way to visit will still be as a member of a research team—one that treads very, very lightly.

This story originally ran on October 8, 2017.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook