How 7 Sisters Made a Fortune off Their Rapunzel-Like Hair

In the late 1800s, the Sutherland women earned millions by marketing a hair-growth tonic.

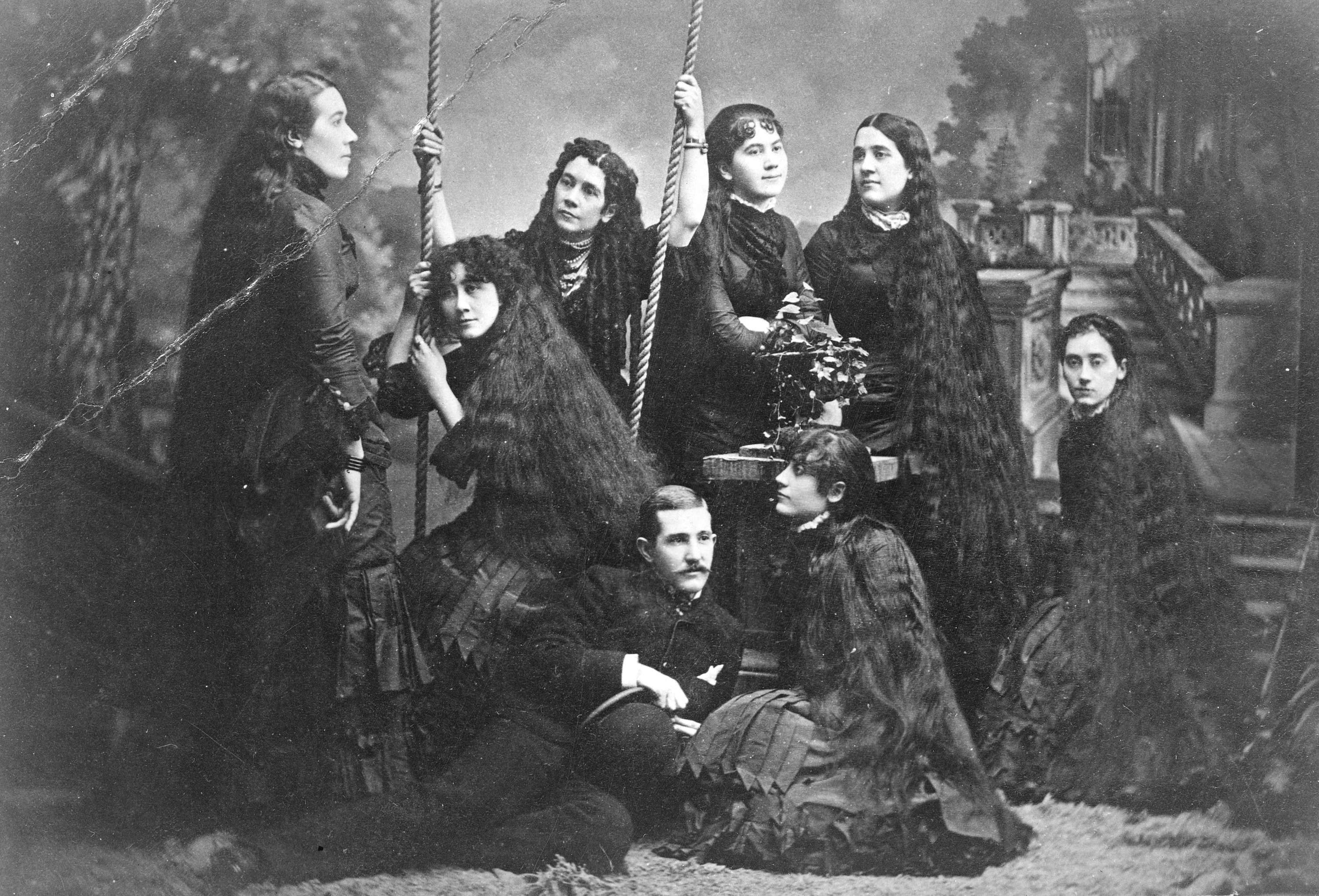

In the late 1800s, seven sisters living near Niagara Falls in upstate New York used their unusual hairdos to become famous and tour the world. They appeared at dime museums, in P.T. Barnum’s circus sideshows, and even at world’s fairs.

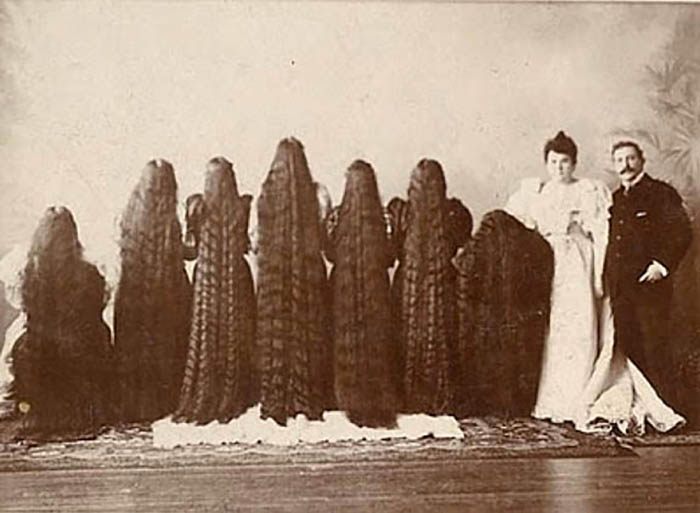

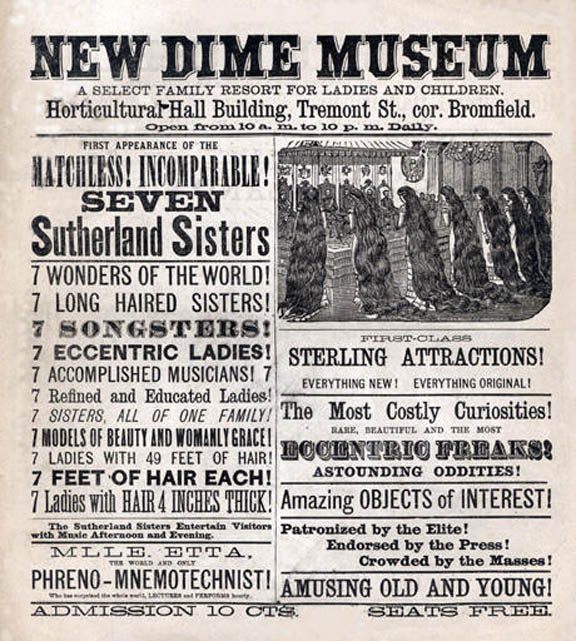

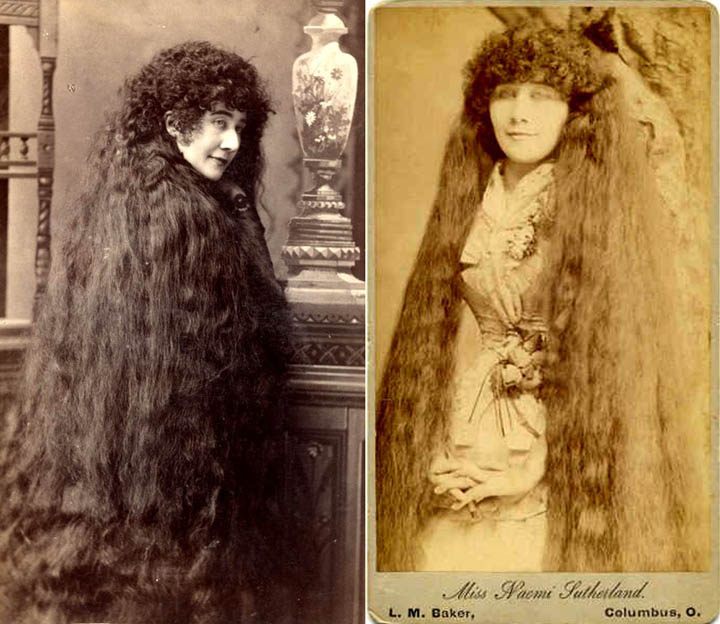

A handbill for one of their appearances called the sisters—Sarah, Victoria, Isabella, Grace, Naomi, Dora, and Mary—the “7 Wonders of the world! 7 Accomplished musicians! 7 Refined and Educated Ladies! … 7 Ladies with 49 feet of hair! 7 feet of hair each!” Onstage, the Seven Sutherland Sisters showed off their musical talents. But what the audience really waited for was their big reveal: when all seven loosened their cascades of dark hair that swooshed down, brushing the floor.

Long, flowing hair on women was considered an important marker of femininity in England and the United States during the Victorian era. Billowing manes figured prominently in the art of the era—in the poems of Yeats and paintings by artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti—imbued with enchanting powers. In Rossetti’s Lady Lilith painting, “the grand woman achieved her transcendent vitality partly through her magic hair … her gleaming tresses both expressed her mythic power and were its source,” according to Elizabeth Gitter’s The Power of Women’s Hair in Victorian Imagination. An article in the late 1800s-era Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine states that a woman’s hair should be naturally abundant and luxuriant—but, above all, it should be long: “It is equally hurtful to the health of females, as it is contrary to their beauty to wear their hair cut a la Brutus, Titus, or Caracalla.”

Long, untrammeled hair could also carry a whiff of the disreputable. When Victorian girls reached a certain age (usually 18), they were expected to put their hair up and let down their hems, signifying that they were now of marriageable age. A respectable woman would only let her hair down, as it were, in private. This sex appeal may have accounted for the Sutherlands’ popularity in sideshows and dime museums, such as P.T. Barnum’s American Museum. The notorious impresario billed them as “the seven most pleasing wonders of the world.”

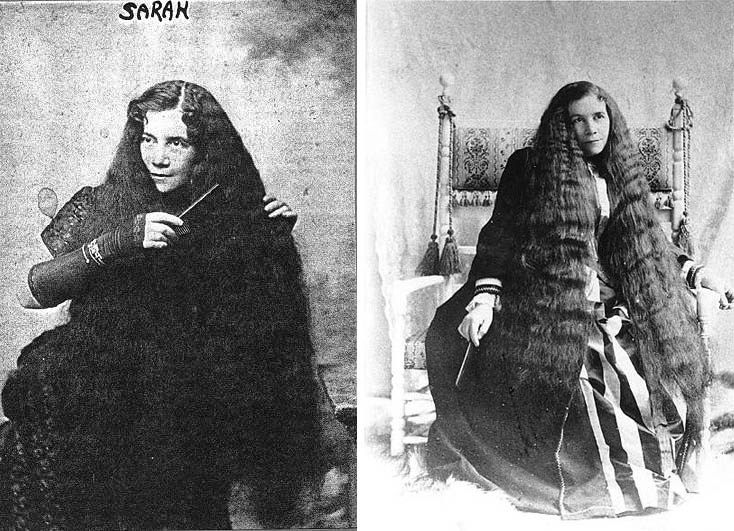

The Sutherland girls, the eldest born in 1846 and the youngest around 1864, grew up on the family turkey farm in upstate New York, near the Erie Canal, Buffalo, and Niagara Falls. Their father Fletcher Sutherland was a sometime preacher who left the farmwork to his wife and daughters. According to Arch Merrill’s Shadows on the Wall: Tales of New York State, the girls’ mother Mary would slather their hair with a stinky ointment that helped it grow…and grow. When they were tending turkeys, no one cared about the stench, but it got them teased at school. Nevertheless, the concoction was effective, judging by the sisters’ Rapunzel manes.

The young women were skilled musicians. Naomi sang in a surprising and beautiful bass, and, by her teens, Sarah was a well-loved local music teacher. Performing at churches, community theaters, and fairs, they were known as the “Sutherland Concert of Seven Sisters, and One Brother,” according to Brandon M. Stickney, author of a biography of the sisters. (Brother Charles was born in 1854 but didn’t continue as a singer.) The sisters toured in New York City and throughout the South, appearing at Atlanta’s International Cotton Exposition and World’s Fair in 1881. In 1883 they toured with the W.W. Cole Circus in Mexico. By 1884 the group was touring with Barnum.

The Sutherland sisters (“7 Refined and Educated Ladies!”) were listed on handbills alongside “The Most Costly Curiosities! Rare beautiful and the most eccentric freaks! Astounding Oddities!” The sisters emphasized their respectability by singing hymns and parlor songs such as “Woodman, Spare That Tree!” and “Come Into the Garden, Maud.” When on tour with the Forepaugh and Sells Bros. Circus in 1883, they were said to have performed before Queen Victoria. But they still belonged to the sideshow, where acts were classified as born freaks (with congenital abnormalities such as missing limbs or gigantism), made ones (tattooed ladies, people with extremely long hair or beards), and novelties (sword-swallowers, fire-eaters, snake-charmers).

In the last quarter of the 19th century and first quarter of the 20th, hundreds of so-called freak shows toured America. “Freak” was a common term, although a group of sideshow employees banded together at the turn of the century to demand that their managers show them the courtesy of exchanging the word “freaks” for “prodigies,” according to a 1907 article in The New York Times. Many performers owed their fame in some way to their hair. Bearded ladies were popular, as was the hirsute Alice Doherty, known as the Minnesota Woolly Girl, and a Russian teen, Fedor Jeftichew, known as Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy for the luxurious pelt of hair that grew up his forehead, merged with his hairline, and continued around to form a handsome beard and mustache.

In the early 1880s, Fletcher realized that the Sutherlands’ hair, more than their musical talent, was the big draw. He and their manager, a showman named Harry Bailey, decided to capitalize on the public obsession with abundant hair. One problem: mother Mary Sutherland was dead and no one remembered the recipe for the original hair grower.

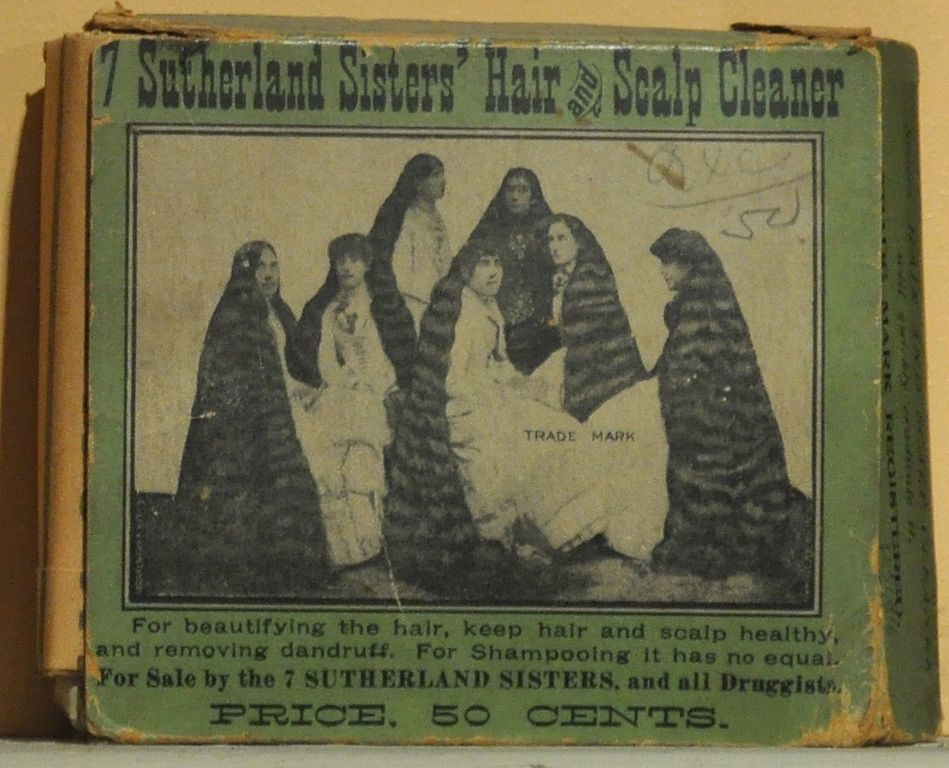

It was the era of patent medicines, and the men came up with a tonic. The company got its first trademark in 1883. “The Lucky Number 7 Seven Sutherland Sisters Hair Grower” cost 60 cents for four ounces, or the equivalent to about $15 nowadays. (The average weekly wage for a railroad engineer that year [1881] was just under $4). It was also sometimes known as “Hair Fertilizer.” Ingredients included borax, salt, quinine, bay rum, and cantharides, an irritating powder made from an aphrodisiac beetle known as a Spanish Fly. “It’s the Hair—not the Hat That Makes a Woman Attractive,” read one ad for the Grower and Scalp Cleaner. A few years after that, a Sutherland Sisters comb and eight shades of “Hair Colorator” followed.

In its first year, the Seven Sutherland Sisters Corporation made $90,000 in sales (about $2.25 million today), according to Douglas Farley of the Erie Canal Discovery Center. He writes that the company eventually had 28,000 dealers and offices in New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago, Toronto, and Havana. By 1890, the sisters had sold over $3 million dollars’ worth of the Hair Grower (some 2.5 million bottles). At the height of their fame, a judge temporarily ordered the sisters to refrain from posing in the window of their Manhattan store because the ensuing crowds were a public disturbance.

The sisters hired long-haired women to demonstrate their products in drugstores and shops around the country. (Occasionally, they had to fill in for Naomi, who had several children before dying young of cancer, and Mary, who had her difficult spells.)

Their fortunes burgeoning, the sisters shifted to touring for the sake of their business rather than as part of a circus. In 1893, they built an elaborate mansion on the site of their former turkey farm. It had bedrooms for each sister, a marble lavatory with hot and cold running water, a turret and cupola, imported fine furniture, massive chandeliers, black walnut woodwork, and hardwood floors, according to Farley.

The sisters’ behavior reportedly became increasingly eccentric. Mary’s room locked from the outside, with a slot for food trays. A young man was married to Isabella, but seemed awfully close to Dora (they all cohabitated for a while). The women were said to have closets full of furs and beautiful dresses, but at home they wore their hair piled up under white-toweling caps. They rode their bikes around the yard in their bathing costumes. The sisters loved their menagerie of pets. The animals were fed the finest steak and chicken and wore handmade sweaters and slept on silk beds. Dora had a Mexican hairless dog named Topsy. When a pet died, the sisters put obituaries in the local paper and had elaborate leave-takings. Topsy’s read: “Deceased Canine Will Have First Class Funeral.”

Had they known about a certain fad that would soon be sweeping the country, they might have reined in their spending. In the 1920s, modern young women, aka flappers, shed their corsets and long skirts to symbolize freedom from stodgy respectability. They also began chopping off their long hair—the era of the bob began.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook