T. Rex Thrived in a Swampy Home, According to Amber ‘Time Capsule’

Fragments of fossilized tree resin suggest the iconic dinosaur ruled an ecosystem similar to the Everglades.

Today, southwestern Saskatchewan is a rugged swell of prairie. But in areas along the Frenchman River, the topography crumples into hilly bluffs and grass gives way to badlands built of layered gray and greenish-brown rock. To paleontologists, these cemented bands of clay and sandstone offer a window into the last days of the dinosaurs, some 66 million years ago.

The Frenchman Formation is a bonanza of late Cretaceous fossils. Iconic species, such as three-horned Triceratops and armor-clad Ankylosaurus, have been found eroding out of these hills alongside “Scotty,” one of the largest known Tyrannosaurus rex skeletons. For decades, however, the environment these animals inhabited has been a question mark. Now, thanks to some of the smallest discoveries at the site, paleontologists are able to piece together the entire ecosystem where Scotty reigned. The new view of the dinosaur’s world comes courtesy of tiny details preserved in fragments of amber—no Jurassic Park-style “dino DNA” necessary.

“Amber is an exceptional medium of fossilization providing a wealth of paleontological information,” says Pierre Cockx, a paleontologist at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum. “[But] I think researchers got more excited about the presence of fossil bones from dinosaurs.” When Cockx began sifting through fragments found alongside Scotty, a couple pieces of cloudy, red amber caught his eye. The fossilized tree resin, overlooked for decades, had never been studied.

Examining amber for clues to an ecosystem is not new. For decades, paleontologists have analyzed insects and other animals—technically known as inclusions—that were preserved inside the material to learn more about their habitat. Amber from Myanmar, for example, containing fossils of everything from snakes and frogs to dinosaur tails and primitive bird hatchlings, helped paleontologists determine that the animals lived in a dense tropical forest 100 million years ago.

The amber from Saskatchewan’s Frenchman Formation is different. Instead of the translucent gold nuggets commonly seen in museums and fossil shops, the Canadian specimens are extremely brittle and fragmentary, most smaller than a grain of rice. The shards are milky and streaked with swirls of orange and crimson, likely due to the resin coming into contact with water before it fossilized. Insects are rarely preserved in the material, much less entire vertebrates. Cockx’s work has shown, however, that this amber is a different kind of time capsule, preserving other environmental clues.

By comparing the molecular makeup of the fossilized material to modern tree resins, Cockx and colleagues determined that the amber likely came from an ancient cypress tree in a Cretaceous swamp. To reconstruct the climate these trees grew in, the researchers analyzed the amber for different forms of elements such as carbon and hydrogen, and then compared them with modern samples. A high concentration of a specific isotope of carbon, for example, hinted that the environment was in the midst of a drought when the resin seeped from the cypress tree. Additionally, a high concentration of a specific hydrogen isotope suggested that the air was likely salty.

While modern Saskatchewan is landlocked, during the Cretaceous, North America was bisected by an ancient marine waterway known as the Western Interior Seaway. Living in an environment just west of this prehistoric sea, the air filtering through a Tyrannosaur’s nostrils would have been warm and salty. The Frenchman Formation has also yielded fossils of cold-adverse crocodilians, which led Cockx and his team to deduce that this part of Canada would have felt like coastal South Carolina 66 million years ago.

In a study recently published in the journal Cretaceous Research, Cockx and colleagues used the data mined from the amber to recreate Saskatchewan’s ancient environment in stunning detail. During the late Cretaceous, Saskatchewan would have been a mosaic of subtropical, swampy forests similar to the Florida Everglades. Towering dawn redwoods would have crowded the horizon as ancient plants including ginkgo and cycads mingled with flowering trees in the understory.

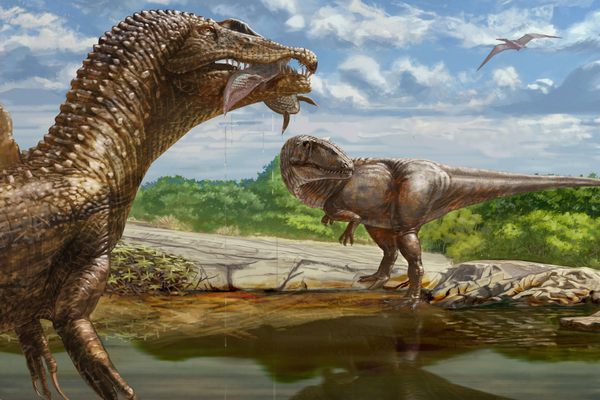

Set along a meandering river, this area was bursting with life. Crocodiles floated between a maze of buttressed cypress trunks while slender-snouted Champsosaurs, an extinct group of reptiles resembling India’s gharials, snapped up fish along the riverbank. On the marshy soil, Triceratops and its horned kin foraged alongside 40-foot-long duckbills called Edmontosaurus, while packs of sickle-clawed Dromaeosaur raptors stalked prey in the shadows.

Onto this boggy stage thundered Scotty and its kin. Estimated to weigh nearly ten tons, Scotty was the apex predator of this ancient swamp. With a heavily armored head brimming with banana-sized teeth, it was capable of dispatching its supersized prey with a single bite—which could exert enough pressure to crush a car. While dinosaurs like Scotty ruled ancient Saskatchewan, mouse-sized primitive mammals—our distant relatives—scurried underfoot, biding their time.

Cockx’s research suggests that the fragile amber offers new context for some of North America’s most famous dinosaur species and their environment. “We can now set the stage and think about what the scenery was like and also what the supporting cast of Scotty’s world was like,” says Scott Persons, a paleontologist at the College of Charleston who described the Scotty skeleton in 2019. “You can really start to reconstruct Scotty’s world at a molecular level.”

Cockx hopes his work will encourage future paleontologists to take a closer look at amber found in dinosaur-rich deposits. As part of his doctorate, Cockx compared the Frenchman material to amber found at Alberta’s Pipestone Creek bonebed, where hundreds of burly Pachyrhinosaurus, a relative of Triceratops, died in an area the size of a football field. Although amber inclusions, including insects and an ultra-rare seabird feather, had been discovered here, many of the specimens gathered dust for decades before Cockx took a look. “There was not yet sufficient interest for studying amber from these sites,” he says. “So, investigating amber is quite a new, exciting way for looking at [these] bonebeds.”

Jingmai O’Connor, curator of fossil reptiles at Chicago’s Field Museum, has studied primitive bird fossils preserved in Burmese amber, and agrees that the fossilized resin represents a new frontier for paleontology. “Amber does have the enormous potential to tell us about paleoenvironments,” she says. “[We’re] only scratching the surface on what these fossils may tell us.”

Persons is intrigued by how this high-definition look at a T. rex habitat may influence our understanding of the apex predator and where it preferred to live. The Saskatchewan amber reveals that Scotty thrived in swamps and patchy forests with room to roam. Which is why, says Persons, the decision by Jurassic Park’s keepers to confine their largest predator to a cramped patch of dense jungle seems so misguided. “That’s not the correct place to put your Tyrannosaurus rex!” Persons muses. “No wonder the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park are so grumpy and desperate to break down the electric fences.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook