The Desert Architecture School Where Students Build Their Own Sleeping Quarters

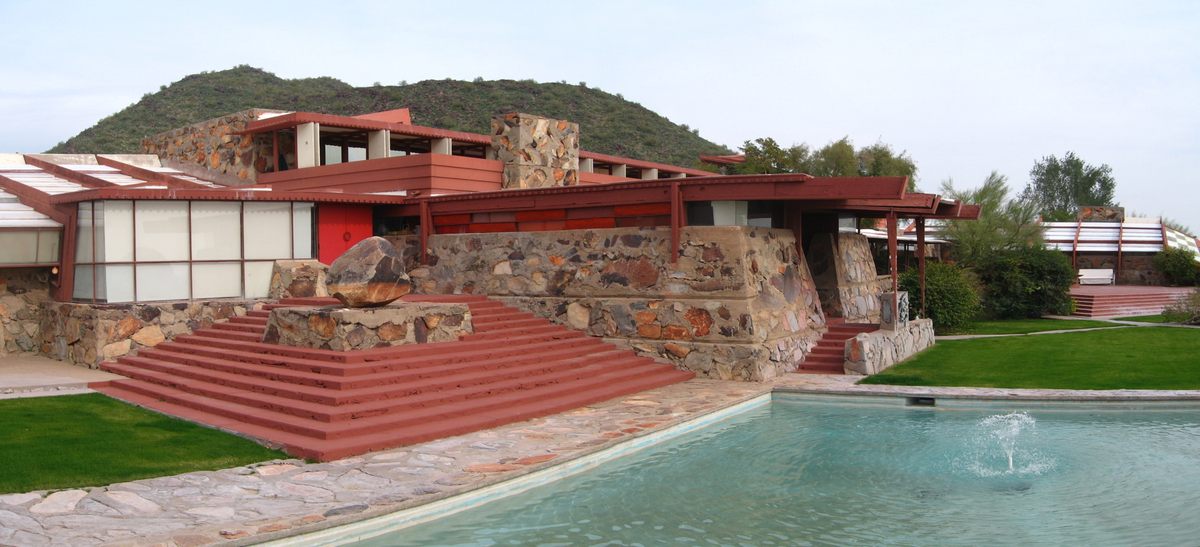

At Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West in Arizona, dorms are DIY.

The first thing Lorraine Etchell sees each morning is the sun rising over the Sonoran Desert and illuminating the iconic Camelback Mountain. She doesn’t even have to leave her bed to become one with the desert: From her mattress, she can see the horizon stretching out before her and watch groups of Gambel’s quail scuttling around the cacti and creosote bushes.

Her view is uninterrupted by city high-rises and accompanied only by the sounds of quail calls and shrieking hawks.

That’s because Etchell is a resident of one of the world’s most unusual dorms. The second-year graduate student at the School of Architecture at Taliesin (SOAT) in Scottsdale, Arizona, lives in a desert shelter, carrying on a tradition started by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1937.

Wright was 70 years old when his doctor recommended that he spend winters in a drier, warmer climate. He and his apprentices began making annual treks from Wisconsin to Arizona, where they lived in canvas tents during the construction of Taliesin West. Taliesin West served as a winter escape from the original Taliesin, Wright’s residence in Wisconsin, and provided a place for the architect’s apprentices to live and learn alongside him.

Wright, known for creating “organic architecture” that prioritizes harmony between buildings and the natural environment, liked minimalist desert living so much that he encouraged his protégés to continue building rudimentary desert shelters after construction was completed. In addition to providing hands-on practice, the shelters forced aspiring architects to become intimately familiar with nature’s impact on living spaces.

The School of Architecture at Taliesin West continued accepting students after Wright’s death, and today, its 20 or so students are still strongly encouraged to try desert living. Most do. The school requires students to build a shelter or enhance an existing one.

“It’s a sense of freedom that I had never felt before. And it’s a powerful thing,” says Etchell, who lives in Japanese House, a 250-square-foot, window-filled redwood structure built in the early 1990s by Ryosuke Isoya, an apprentice from Japan. The shelter sits on a cantilever and creates the sensation that “you’re hanging, in this sort of nest, this perch … You’re protected [from nature], but you’re not separated.”

During the day, Etchell’s routine resembles that of architecture students at other schools: Go to class, eat in the dining hall, work on projects in the studio until obscene hours. But when it’s time to go to bed, she changes and washes up in a communal locker room where her clothing and toiletries are stored. Then, wearing shoes underneath her pajamas, she walks a half-mile or so into the desert.

The path is strewn with loose stones and prickly cacti, and dangerous animals like rattlesnakes and scorpions come out at night. These obstacles are shadowy under a full moon and much harder to make out on a moonless night. Still, most students say they can navigate safely to their beds by muscle memory, no flashlight needed.

Most shelters are more exposed to the elements than Etchell’s, consisting of a roof and a bed platform and little else. Some students simply live in tents.

“The original sheep herder tents were very ephemeral … a simple masonry base and the canvas tents would be disassembled and stowed away for the summer when the students were in Wisconsin,” says Etchell. “Most recent shelters require continuous maintenance.”

“They’re strong-willed, to be out here in these shelters, to say the least,” teaching fellow Ryan Scavnicky says of his students. Although he says living in a desert shelter is “something I never would have done,” Scavnicky calls the structures “unique and super fun.”

That’s partly thanks to special zoning rules that essentially create an architectural sandbox in the Taliesin West desert, allowing students to experiment without running afoul of city regulations. As for how long the shelters last, that’s “in direct proportion to what they are made of,” says Christopher Lock, a SOAT student. “Structures of thin canvas and wood often blow away within a year or two, other wooden frameworks may hold on longer—but the dry air makes them brittle and rain, sun, and wind often warp them over time.”

Some of the most visually arresting shelters—like “Hook” and “Hanging Tent”—have serious flaws. Hook’s cutting-edge design was featured in magazines after it was built in 2003, but it had no protection from rain, sun, and wind. (It was made more livable with the addition of a plexiglass roof and canvas walls last winter.)

“Hanging Tent” floats beautifully five feet above the ground, but its construction broke with the principles of organic architecture by creating a path of destruction through the desert. The design missteps, however, are an important learning process that won’t impact any clients and can be modified by future architects-in-training.

“You can’t live like this and not have this slowly permeate your conscious,” Lock says of the shelter program. “I doubt that anybody who goes through this program, living several years like this, is going to make a dead room, is going to make a boring ho-hum bit of architecture.”

Lock says that “‘normal’ houses seem so dead to us, because they’re just boxes of drywall” with “no air moving, there’s no nature, there’s no light.”

Although Etchell will meet the design requirement with a structure in Wisconsin, where students spend the summer months, she’s already left her mark in Scottsdale. When she first set eyes on Japanese House, it was hardly the elegant space it is now. Students were at one point forbidden to enter for safety reasons and the school was considering tearing it down.

With the help of her construction-savvy fiancé, Etchell tore out rotting structures, replaced the missing ceiling, cleared out pack rat nests, created a built-in desk, and oiled and painted the floor.

She relishes the shelter’s simplicity and lightness, and finds herself returning to it during the day if she grows creatively frustrated.

“I spend most of my time in the study area where my desk is. And I’m so happy to have that, because to get into your creative mode, it’s hard to do in the studio,” she says. But “to be sitting in this room, this entire room that is literally floating on these two tiny little rods? Yeah. I’m interested in that.

“The whole valley opens up and there’s nobody in front of me,” she adds dreamily, taking a sip of tea. “Every morning is different, every evening is different, every time of day is different. And I am alive, in the shelter that is living with me. And that’s natural architecture.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook