The 1980s Crime Ring That Poisoned Japan’s Candy And Never Got Caught

The “Mystery Man with 21 Faces” mocked the police ruthlessly and stocked Japan’s supermarkets with cyanide-filled candy. To this day, no one knows who they were.

Police officers check Glico products at a supermarket in Osaka, Japan, in December 1984. (Photo: Sankei Archive/Getty Images)

By now, everyone knows there’s no such thing as poisoned Halloween candy. No chemically laced chewing gum. No razor blades hidden in caramel apples. Researchers have spent years debunking this urban legend, which, they say, was born from a certain strain of cultural anxiety—fear of strangers, of uncertainty, of too much sugar. Almost certainly, the cruelest thing a neighbor will do to your trick-or-treating kid is hand them a toothbrush.

But about 30 years ago, across much of Japan, this irrational, deep-seated fear actually came true. Over the course of a year and a half, a cryptic group blackmailed the country’s biggest candy companies. They filled supermarket shelves with cyanide-laced chocolates. They wrote elaborate, teasing letters detailing their exploits, which were published in national newspapers. They consistently foiled the nation’s police force. And to this day, no one has any idea who they were.

They called themselves the “Mystery Man with 21 Faces,” and they replaced a whole country’s sugar highs with a rush of terror.

A Glico billboard in Osaka, Japan. (Photo: Sakaori/CC BY-SA 3.0)

On March 18th, 1984, Katsuhisa Ezaki came home from a long day at the office, took off his suit, and sunk into a warm bath. Ezaki was coming up on two years as the president of Ezaki Glico, a multimillion-dollar corporation based in Osaka. The company sold everything from ice cream to hamburger meat, but was most famous for its sweets—Pucchin Puddings, Pocky chocolate, and Glico caramels, made with health-boosting oyster glycogen.

Ezaki had only been soaking for a few minutes when he heard a brief commotion elsewhere in the house. Suddenly, two armed, hooded men burst into the bathroom and began dragging him out of the tub. Ezaki cried out for help, but his assailants were two steps ahead of him—they had already tied up Ezaki’s wife and daughter and cut the house’s phone lines, and they had even broken into the house next door, where his mother lived, and tied her up, too. The men muscled Ezaki out the door, gave him a coat and a ski hat, and brought him to an isolated, anonymous warehouse.

The next day, as police scrounged for some sign of their whereabouts, a ransom note was found in a nearby phone booth, demanding a billion yen (about $4.3 million in 1984 US dollars) and 220 pounds of gold bullion. Detectives were just starting to chase down leads when, after two days in captivity, Ezaki managed to escape his warehouse prison. Everyone hoped that the perpetrators would be caught, and that that would be the end of it.

It wasn’t. It was only the beginning.

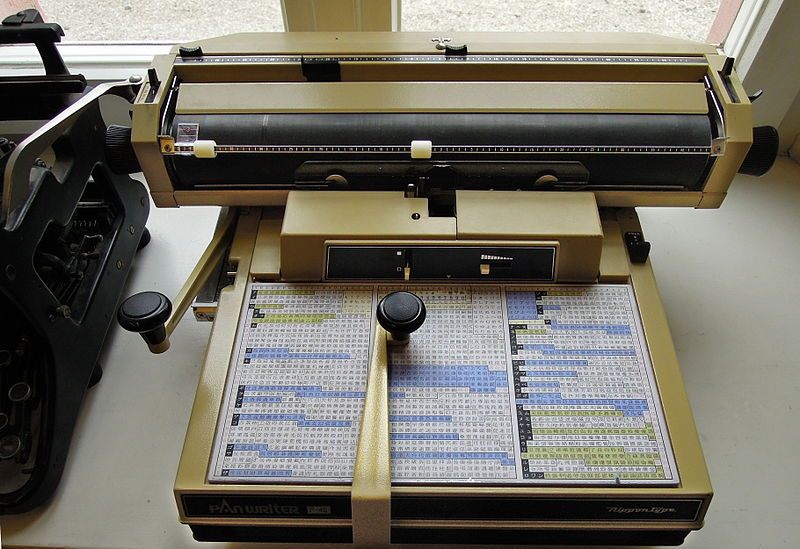

A panwriter—the typewriter of choice for the Mystery Man with 21 Faces. (Photo: LoKiLeCh/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Three weeks later, newspaper offices across Japan received copies of a strange letter. “To the stupid police,” it began. “Are you idiots?… If you were pros, you would catch us. Because you guys have such a high handicap, we’re gonna give you some hints.”

The letter went on to give more details about the crime—the getaway car was gray, the food they purchased was from Daiei Supermarket, one of the largest chains in Japan. “Should we also kidnap the head of the prefectural police?” it wondered. The missive was signed kaijin nijuichi menso—which translates, roughly, to “The Mystery Man with 21 Faces.”

The newspapers published the letter. Over the next few months, they published its follow-ups, too: there were dozens of them, filled with taunts, jokes, and more useless clues. Some served mostly to goad the police. Others revealed further potential crimes: in one, sent in mid-May, the gang alleged that they had laced several packages of Glico candy with cyanide. They didn’t specify which kind.

Glico immediately recalled all of its candy—which tested negative for cyanide—but they couldn’t rescue their reputation. The frightened citizens of Japan engaged in a de facto Glico boycott. “Typical of the nationwide concern was a Tokyo office worker who gave her colleagues a gift of chocolates, attaching a reassuring note that another candymaker had produced them,” the New York Times wrote. The company’s assets plunged, and they had to lay off 1,000 workers.

While Glico’s reputation foundered, its media-savvy tormenters grew more and more infamous. As anthropologist Marilyn Ivy explains in “Tracking the Mystery Man with 21 Faces,” the gang named themselves after the “Mystery Man with the 20 Faces”—a villainous, shapeshifting thief invented by popular detective novelist Edogawa Rampo. “In every neighborhood and in every house wherever two or more people are gathered,” Edogawa wrote, introducing the character, “they talk about the mystery man with the 20 faces, just as naturally as if they would talk about the weather.”

Ezaki Glico headquarters, in Osaka, Japan. (Photo: Bakkai/CC BY 3.0)

This new gang of Mystery Men also captured the public imagination, even as they themselves evaded capture. Their letters and tactics were theatrical and morbidly fascinating. They would demand huge amounts of cash, and then fail to turn up to collect it. (There is no evidence that they ever accepted any money.) Once, they instructed Glico employees to appear at a particular phone booth at a certain time to await a message—but when disguised police showed up instead, they didn’t call.

“You thought you could fool us, dressed up in your nice businessmen’s blue suits, acting like salary men,” they wrote the next day. “But those shifty eyes gave you away.” Somehow, they had been watching. “We do not recall a case in which criminals have made such fools of the police,” the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun wrote in an editorial.

Their letters were also written in a dialect associated with Osaka, Japan’s third largest city, which is seen as an unpretentious anti-capital. Compared with the formality of standard Japanese, says Ivy, Osaka slang left room for warmth, sincerity, and humor. The city has been associated with comedy for more than 1,000 years, and many of Japan’s most well-known comedians hail from Osaka.

“By writing in this dialect, the authors displaced the often murderous intent of their words into the realm of the lucid,” she writes. In other words, when Japanese citizens opened their papers and read the latest threat from the Mystery Man with 21 Faces, a certain subtext also got across: Why so serious?

In June of 1984, in a letter addressed “to our fans throughout Japan,” the Mystery Man announced that they would lay off Glico. “The president of Glico has already gone around with his head hanging down long enough,” they wrote. “We would like to forgive him.” They also got in a few final jabs at the candy company (“In our group there’s also a 4-year-old kid—every day he cries for Glico… It’s a drag to make a kid cry cause he’s deprived of the candy he loves”) and at the police (“The police have done a good job—hang in there and don’t give up!”).

Finally, they made a promise: “Japan has gotten terribly hot and humid,” they asserted. “So when our ‘work’ is done, we want to go to Europe—Geneva, Paris, London—we’ll be in one of those places… Let’s bring Pocky—the traveler’s friend! Delicious Glico products—we’re eating them too! See you in January of next year!”

A 7-11 in Japan, the kind of place where the poisoned candies were found. (Photo: Japanexperterna/CC BY-SA 3.0)

But the Mystery Man returned long before that. In September, they called up Morinaga, another long-standing candy company, and demanded $400,000. Morinaga didn’t comply. So on October 8, 1984, Japan’s newspapers got yet another letter:

“To moms throughout Japan:

In autumn, when appetites are strong, sweets are really delicious.

When you think sweets—no matter what you say—it’s Morinaga.

We’ve added some special flavor.

The flavor of potassium cyanide is a little bitter.

It won’t cause tooth decay, so buy the sweets for your kids.

We’ve attached a notice on these bitter sweets that they contain poison. We’ve put twenty boxes in stores from Hakata to Tokyo.”

Police swarmed grocery stores in and around the cities of Kyoto, Osaka, Kobe, and Tokyo, scouring shelves for poisoned candy. Sure enough, they found boxes of Morinaga Choco Balls and Angel Pies with extra labels—“Danger, contains poison. You’ll die if you eat this. The mystery man with 21 faces.” This time, the candy actually did test positive for cyanide.

Immediately, Morinaga’s stock dropped 22 cents. Further letters promised that if supermarkets didn’t immediately begin boycotting Morinaga, future boxes would appear, this time unlabeled. “It’s going to be like a treasure hunt,” the Mystery Man said.

The police mobilized like never before. Noting that the Mystery Man tended to strike on Saturdays and Sundays, 40,000 officers—20 percent of Japan’s entire force—spent several weekends in a row staking out supermarkets. They pored over surveillance video from one of the grocery stores, which showed a man with curly hair, a baseball cap, and glasses placing something on a shelf. They traced the provenance of the typewriter on which the letters were written. They released audio from the blackmailing telephone call to Morinaga, which featured a woman and child demanding money, and even set up special phone lines so that people could call in and listen to it.

But every lead went cold—and led to more mockery. “Isn’t the man in the video a splendid chap?” one follow-up letter read, before comparing his appearance to several well-known police captains. After a failed stakeout in Shiga Prefecture yielded a van full of strange equipment—a vacuum cleaner, a floppy hat, wire cutters—the Mystery Man with 21 Faces wrote again, promising “you won’t be able to trace us from anything we leave behind.”

They kept demanding money from candy companies: 100,000,000 yen from Fujiya Co., 50,000,000 from Surugaya. In August of 1985, Shoji Yamamoto, the head of the Shiga Prefecture police—who blamed himself and his subordinates for failing to capture the Mystery Man during the stakeout—doused his body with kerosene and lit himself on fire.

This was too much even for the Mystery Man. Five days later, they sent out their last letter. “No-career Yamamoto died like a man,” it read, in part. “So we decided to give our condolence. We decided to forget about torturing food-making companies… We are bad guys. That means we’ve got more to do other than bullying companies. It’s fun to lead a bad man’s life. Mystery Man with 21 Faces.” With that, they disappeared.

Milk caramels from Morinaga. (Photo: Solomon203/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Over the next few years, police continued to search for clues, and to haul in suspects. Some leads pointed to the infamous Yakuza mobs. Others suggested extreme left-wing or right-wing groups, or North Korean communists. All told, the police investigated 125,000 people, and followed up on 28,300 public tips. But nothing illuminating was found, and everyone’s alibis checked out.

In 1995, the statute of limitations ran out on Ezaki’s kidnapping. In 2000, it expired on the poisoned candy case. As Michael Newton notes in The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes, “Even if identified today, [the Mystery Man with 21 Faces] and his various accomplices could not be charged or tried.”

And so, their 21 faces still intact, the Mystery Man lives on—in minds that recall their missives, in hands that hesitate before reaching for a piece of Pocky. Because they could be anyone, they’re everyone. Because they could strike anywhere, they’re everywhere. As they themselves wrote in one letter, midway through their reign of terror:

“Who are we? Sometimes a policeman, sometimes a violent gang… Sometimes a factory hand, sometimes a kidnapper… but our true identity is… The Mystery Man with the 21 Faces!”

And that is all we may ever know.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook