The Art of Ice Tunneling and the Army’s Failed Frozen Base

Leanne Wijnsma digging into the frozen ground in Austria (Photo: Renate Mihatsch)

Leanne Wijnsma has dug her share of tunnels. More than her share–over the past two and a half years, the Amsterdam-based artist has dug down into the dirt more than a dozen times and on two continents. “There is simply something magical about it that can’t make me stop,” she says. But after digging 15 tunnels, she decided to only dig tunnels that presented a unique challenge or a “whole new experience.” Like, for instance, digging through snow and frozen soil.

In January, she dug into the ice for the first time, in a snowy field in Austria, at the minus20degree Art & Architecture Biennial. She expected digging the tunnel to be tough, so she reserved five days for it. She started by clearing the snow away from ground and working on the frozen soil below. By the third day, she says, her wrists hurt so much from wielding a pickaxe that she was afraid she wouldn’t be able to use her computer the next week.

The pursuit of personal tunneling is always a bit mysterious to people who’ve not tried it. People like Wijnsma who have find it meditative: “Like an extreme sport, it puts life into perspective,” Wijnsma says.

Under the right circumstances, ice tunneling–whether through ground or glacier–is an art all its own. Creating a winter tunnel might seem like the sort of endeavor that should only be undertaken for practical purposes—to reach a barn to feed the animals, after a heavy blizzard, perhaps.

But really, the best reason to build tunnels of ice and snow is if it seems like it might be fun, or beautiful. It is never a sensible endeavor: the U.S. Army once tried to make an entire base of tunnels dug into the Greenland ice and snow, and it never quite worked.

Camp Century (Photo: U.S. Army/Wikimedia)

In the early 1960s, the Army initiated “Camp Century” in Greenland. They dug giant trenches into the snow, reinforced them with half-cylinders of metal walls and roofing, and covered the tunnels with snow. The goal, in part, was to test polar construction techniques, but there was also a nuclear generator inside. Walter Cronkite visited in 1961.

Soon, though, the Army decided that an underground ice city, housing 100 men, was less than desirable. Their ultimate aim, it was revealed many years later, was to house nuclear weapons in Greenland–generally the sort of project for which one wants stable storage facilities.

In 1966, after concerns about the structural integrity of the tunnels came up, the Army abandoned the project.

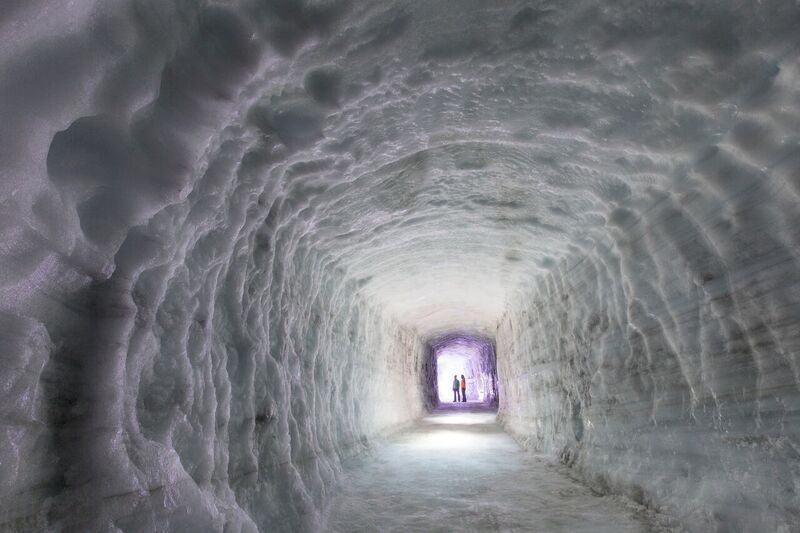

Inside Langjökull (Photo: Into the Glacier)

Perhaps the world’s most dramatic example of an ice tunnel is carved into Langjökull, an Icelandic glacier that is Europe’s second largest. After months of work, a group of Icelanders opened their creation up to the public in the summer of 2015. Known as ”Into the Glacier”, it serves no clear purpose.

It’s about a third of a mile long, and once inside, crampon-clad visitors can walk the tunnels and gaze at the interior of the giant mountain of ice, where beautiful “blue ice” forms. There’s a wedding chapel, too.

There’s certainly something educational about being inside a glacier–perhaps it will help people understand what we’re losing because of climate change. Mostly, though, it just seems cool.

Another glacial tunnel (Photo: Into the Glacier)

Ultimately, ice tunneling is at its best when it’s pursued as an escape, not a practical endeavor. As Wijnsma says of tunneling, “Reaching the other end is freeing.”

Prince Edward Island’s Marcel Landry seemed to understand this dynamic instinctively. The resident of eastern Canada achieved a momentary renown in 2015, after he dug a snow tunnel from his house to his car after a blizzard dropped about three feet of snow. The drifts by Landry’s house were high enough that he could stand up straight in his tunnel.

When asked why he decided to create the passage, its practical function was not first on his list of reasons.

“I knew I would have to dig out eventually,” he said., “so why not start now and have a little fun with it?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook