The Lovable Syrian Brown Bear Who Fought For His (Adoptive) Country

A soldier, possibly Peter Prendys, helps Wojtek engage in his favorite activity—snacking. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

On Friday*, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that, among other provisions, bars all Syrian refugees from entering the United States indefinitely. The order has closed the U.S. even to the small percentage of Syrians who are fortunate enough to have escaped their tumultuous country, registered with the U.N., and passed a years-long vetting process.

As Americans across the country express their disagreement with the ban, it’s a fitting time to remember one refugee who did great things not just for his adoptive country, but for his entire adoptive species—Wojtek, a Syrian brown bear who, by banding together with Polish soldiers, helped the Allies win a crucial World War II victory, and lifted the spirits of people who really needed it.

In the 1940s, as military powers shattered the boundaries of Europe, the people who lived there were violently shuffled around like so many puzzle pieces. Many residents of Poland, who had been shipped to camps in Siberia after their country was divvied up between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, found themselves adrift when alliances shifted and they were released from the Gulags in 1941. Free, but far from home, people of all ages traveled by foot from Siberia to various destinations. Some found purpose, and a place to go, after the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement, which allowed for commander Władysław Anders to form a Polish army on Soviet soil.

By March 1942, the army was too large for the Soviet authorities to feed, so they set off to join the British High Command in the Middle East. It was a long, rough walk, stretches of march punctuated by encounters with others whose lives had been similarly disrupted by the war. For the 22nd Artillery Supply Company, one of these encounters was with a shepherd boy who was hungry enough to approach the soldiers, and ended up trading a burlap sack for a Swiss army knife, a chocolate bar, and a tin of beef. But the most fateful was with the resident of said burlap sack—a tiny bear cub, recently orphaned by hunters.

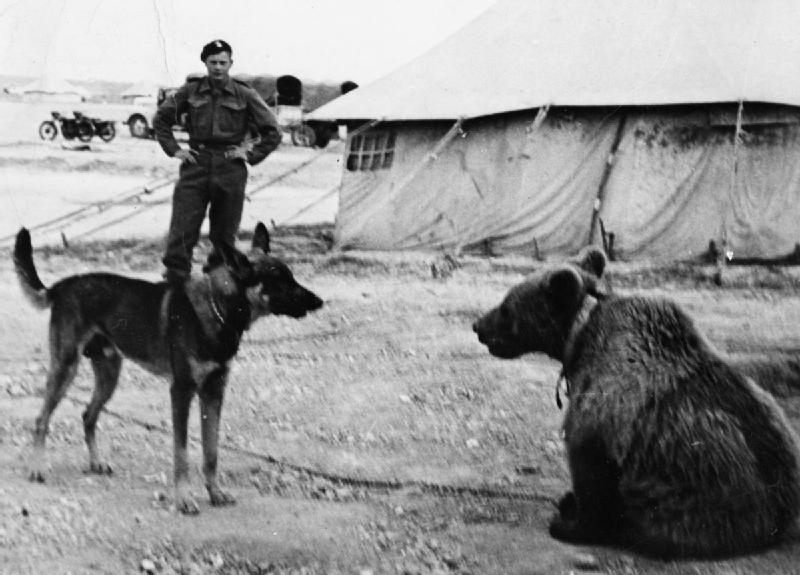

An army dog eyes the new recruit in 1942. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

The shepherd had likely been planning to raise the cub as a dancing bear—not a great job for trainer or animal. Instead, the soldiers took him on as a mascot. They named him Wojtek (short for Wojciech, which means ”joyful warrior”) to instill a fighting spirit in him. They weaned him on condensed milk from an empty vodka bottle, and assigned him a caretaker, a soldier named Peter Prendys who had also been separated from his family in the conflict.

Soon, the 22nd Artillery reached their destination—the town of Gedera, on the edge of the Negev desert in what was then Palestine. Prendys quickly set about teaching the bear how to be a good soldier, marching next to him in the desert heat, training him to wave and salute, and, occasionally, disciplining him when he stole from the provision tent.

Wojtek took to the job. He spent his cubhood as a particularly precocious Army brat, hanging his head out of the artillery truck window during supply runs to Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and Lebanon (and later, when he got too big, stowing away in the truck bed). Between missions, he hung out in the camp, begging shamelessly for snacks, racing with the camp dog (a large Dalmatian), and climbing palm trees. He took on a variety of soldierly habits—he developed a taste for lit cigarettes, which he would puff on once before swallowing, and loved beer so much that when he had exhausted a bottle, he would peer into it, “waiting patiently for more.” At night, he wrestled with the men—he generally went easy—and then joined them around the campfire (and, sometimes, in their tents to sleep). In the morning he woke up and immediately sought out whoever was on early patrol. If left alone for too long, he would put his head in his hands and whimper.

A Syrian brown bear enjoys the water. (Photo: Stahlkocher/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

Wojtek was no show bear, though. Once, he even caught a spy. A thick-coated animal stationed in a hot desert, Wojtek’s favorite treat was a cold shower. He went to great lengths to procure them, standing near the bathing tent and whining until a sympathetic soldier turned the nozzle on him, or decided to dig him a mud bath. Eventually, he learned to turn the shower on himself, and spent so much time there that he was banned from entering without supervision. One day he was delighted to find the door open, but when he barged in, he interrupted a local dissident who had planned on stealing the stockpiled ammunition. The poor guy screamed and surrendered. Wojtek got two beers and unlimited shower time that day.

His curiosity got him into other scrapes, too—he once stole an entire clothesline’s worth of women’s underwear from a Polish signals unit during a supply run to Iraq—but he kept his record clean enough that, when the 22nd Artillery was set to ship out to Italy to join the Allies for a major campaign, he was able to officially enlist. Now with a rank and number—and, most importantly, guaranteed rations—Private Wojtek set out for Italy with the rest of the unit on February 13th, 1944. The Italian campaign was long and strenuous—“very often it was necessary to drive day and night, our heavy lorries filled with munitions and other military materials,” remembers Professor Wojciech Narebski, a member of the regiment. During this time, he says, just the sight of their “extraordinary nice mascot” lifted their spirits.

A 22nd Artillery Badge, bearing the image of Wojtek carrying a shell. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

But Wojtek became famous for lifting other things. Just a few months after their arrival in Italy, the 22nd Artillery found themselves thrown into the Battle of Monte Cassino, the largest European land conflict of the war, and the cause of over 60,000 eventual casualties. The German army had turned the small mountain pass into a stronghold for their defensive line, and the Allies needed to break through in order to move on to Rome. Wojtek’s unit was tasked with driving huge trucks of ammunition to enemy lines via steep winding mountain passes, unloading the stuff, and then driving back to the stockpiles.

During the battle it was all hands on deck, and Wojtek was left alone. But the bear, at this point, essentially thought of himself as a soldier—or, at the very least, had learned that copying what people did earned him praise, attention, and treats. So when he saw soldiers carrying the crates of shells from the trucks to the battle line, he did so too, braving the gunfire and the shouting. He was helpful enough that when he got bored or tired, his comrades coaxed him back into action with snacks.

The Allies won the battle, and word of their ursine warrior stretched far and wide. The 22nd Company drew up new regalia featuring Wotjek, in silhouette, carrying a shell. As historian Aileen Orr puts it in her excellent book about Wojtek, the bear “had pretty much become a legend in his own not inconsiderable lunchtime.”

Wojtek wrestles with the troops during his first tour of duty in 1942. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

He may have let it go to his head a bit, and for him, the rest of the Italian campaign was a series of capers: he tried to hunt horses and donkeys, danced on top of at least one roadside crane, and scared so many people swimming on the Adriatic Coast that Orr calls him “the furry Jaws of his time.” His postwar life was similarly impish. When the fighting ended, Wojtek and many of his fellows ended up at the Winfield Camp for Displaced Persons in Scotland, where he quickly became a local celebrity, and a comfort to yet more displaced people. “They were stateless, homeless, and penniless; the only things they owned were a few meagre possessions in a bag—and a bear,” Orr writes. His campmates showed their love by building Wojtek a swimming pool and taking him on field trips to local dances, where he lolled near the baked goods tables and listened to the fiddles, which calmed him. Even there, in the grip of intense rationing, ”he had two bottles of beer a day,” and all the food he needed, says veteran Jock Pringle. Wojtek in turn showed his appreciation by being a chick magnet at said dances, and by helping those veterans who had found work as farm laborers to carry fenceposts through the Scottish fields.

Wojtek enjoying Winfield Camp in 1945. (Photo: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

Slowly, Wojtek’s fellow soldiers became less displaced, settling more permanently in Scotland or setting off for other shores. But for Wojtek, the camp was home, and the soldiers were his family. He had not the faintest idea of how to be a wild bear—pretending otherwise would have gotten him attacked by his own species or shot by his adopted one—and life in Soviet-occupied Poland wasn’t even that great for people, let alone larger mammals. With great regret, Prendys made arrangements to send Wojtek to the Edinburgh Zoo. The bear drooped in captivity, but he did get a lot of visitors, and they knew what he liked. For the rest of his days, his campmates came by to see their friend, cooing at him in Polish, tossing him candy and lit cigarettes, and, sometimes, jumping into the cage to wrestle.

Wojtek died in the zoo in December 1963. But to this day, his memory helps the soldiers he served with, giving them an entry point to talk about the war with those who didn’t experience it. The bear’s continued service is borne out by the many memorials to him scattered throughout different countries. One, a statue that started going up this past weekend, depicts Wojtek and Prendys walking together, the man’s hand on the bear’s shoulder. They look like a steelier Winnie the Pooh and Christopher Robin, making their way not into some idealized forest, but through the messy, border-tangled world we all live in instead.

*1/30/17: This article has been updated to reflect recent events.

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook