The Bizarre Drama Over the Internet’s Domain Naming System

Ted Cruz is involved.

(Photo: Gage Skidmore/CC BY-SA 3.0)

If you’ve ever registered a website, you may have dealt with the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), but for a lot of others, it remains an obscure part of the internet—only crucial when battling to secure a dream URL.

ICANN is the nonprofit that, among other duties, oversees top-level domains, which are the parts of URLs that you find at the very end: dot-com, most commonly, but also thousands of others. ICANN was founded in 1998 to be the steward of such top-level domains, known as TLDs, and it has been overseen since then by the U.S. government.

But on Saturday, the government, in a long-planned move, is set to give up its oversight of the organization, leaving it in the hands of a diverse group of international stakeholders, including an advisory panel that is composed of an array of representatives from governments across the world.

This has some people, like the Republican Senator Ted Cruz, upset. (“Don’t Let Obama Give Away the Internet,” a press release on Cruz’s website blared in August.) Cruz’s concerns, such as they are, are a mixture of make-America-great-again style bombast coupled with a more serious warning, that putting ICANN in the hands of the world could undermine American national security. How? By potentially giving foreign governments the capacity to undermine or sabotage our internet infrastructure.

There are many reasons why that probably won’t happen, but the most persuasive might be the simplest: ICANN, despite the fact that it controls TLDs, is less a key cog propping up the internet than a vast, mostly administrative registry. Think of it more like a library’s card catalog, a place that helps keeps track of a lot of information, but has almost nothing to do with the information itself.

Still, Cruz’s concerns do shine a somewhat uncomfortable light on an organization that has had a swift 17-year rise, as the infrastructure behind the Domain Name System evolved from a single man with a notebook to ICANN, which has hundreds of employees and a budget of over $130 million. Who are the functionaries behind the world’s URLs?

In the beginning, the internet was mostly just numbers, or, more specifically, Internet Protocol addresses, a string of numbers that would lead you to a website. But numbers are hard to remember, so a guy named Jon Postel, one of the founders of the internet, decided to construct a system in which a lettered name could be attached to those numbers.

Thus was born the Domain Name System (DNS), and, originally, seven top-level domains: .com, .org., .mil, .gov., .edu, .net, and .arpa, to represent companies (hence the dot-com), organizations, military, government, colleges, networks, and the internet’s technical infrastructure, in that order.

Jon Postel, a founding father of the internet. (Photo: Carl Malamud/CC BY 2.0)

But Postel was just one man, keeping track of domain names in a notebook, and, as the web got larger and larger, he and his colleagues sought a system that could scale. The U.S. government, similarly, was interested in a more formalized system, in part because many government agencies were among the internet’s biggest users.

In January 1998, Postel nudged along ICANN’s creation with a stunt, by rerouting a good portion of the internet through servers at the University of Southern California, where Postel was based, instead of government servers in Virginia. The action spooked federal officials, who, within days, announced plans for what would become ICANN. By September 30 of that year, ICANN was formally incorporated in Los Angeles.

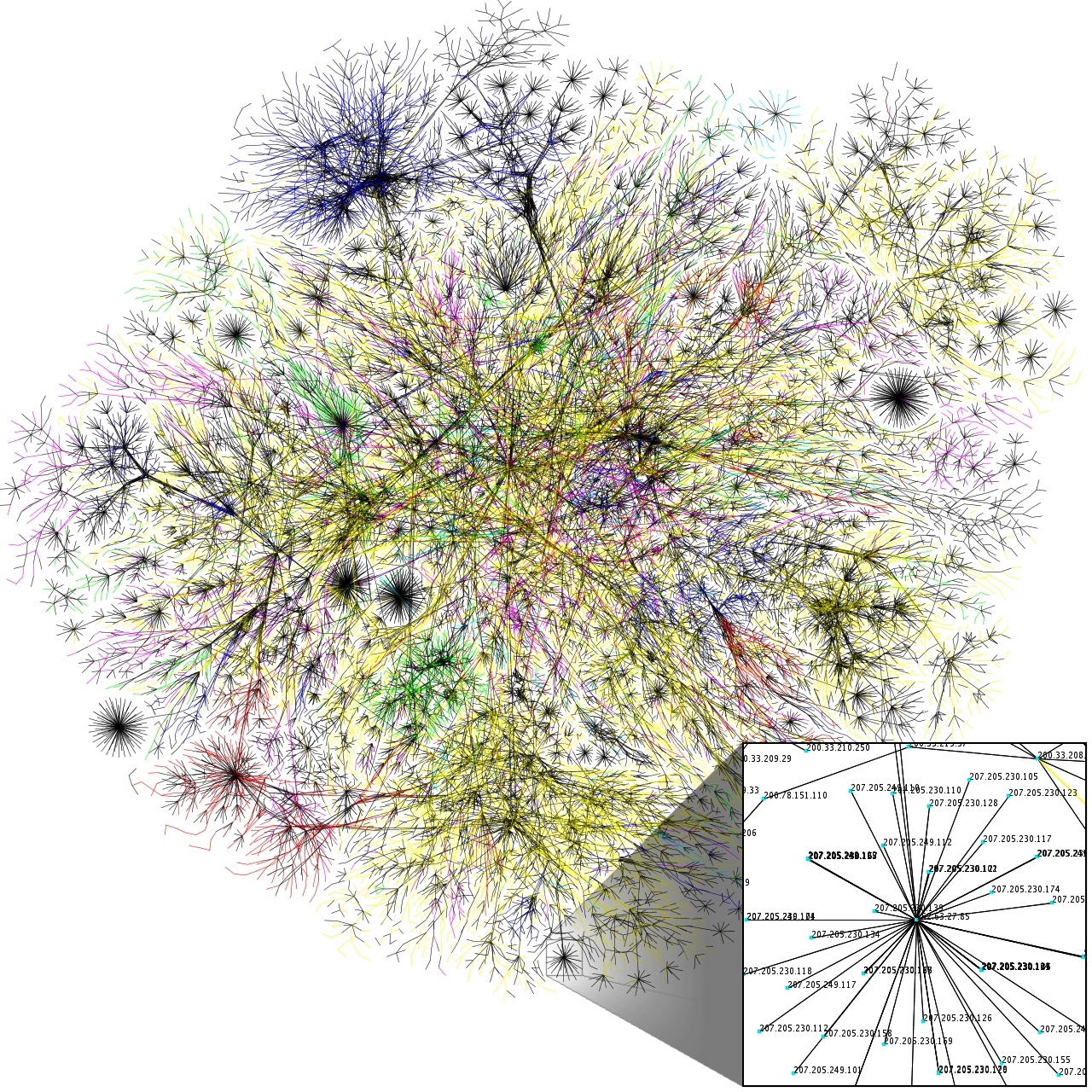

The web, at that time, was in the midst of the dot-com bubble, and the government’s oversight at the beginning was meant to be temporary, but with each passing year, in part because of simple inertia, the U.S. retained their oversight role. The situation, in turn, became the source of an ever-increasing amount of angst from foreign governments and users, some of whom questioned the U.S. government’s motives, and others who simply thought that no government should have a role in a free and open internet. That’s not to mention that by the mid-aughts, the web had gone from Cold War-era government project to something resembling a global public utility.

A visualized map of the internet from 2005. (Photo: The Opte Project/CC BY-SA 2.5)

From the U.S.’s perspective, its oversight over ICANN also presented some unsavory hypotheticals. What if Russia or China, miffed with the U.S.’s continuing influence over the internet, decided to start their own private internets, beyond the scope of the world’s scrutiny? The U.S. was also wary of the United Nations potentially trying to step in. The internet, Republican and Democratic administrations have long argued, should be independent of everyone.

Still, it wasn’t until March 2014 that the Department of Commerce said that it was finally ready to let go, after over 15 years of overseeing ICANN. The U.S. said then it would hand over the reins once ICANN developed safeguards to ensure that it would remain a place governed by every internet stakeholder, from users, to governments, to businesses, to civil society groups. And in June, the government said they were satisfied that it had, setting the formal end of oversight for October 1, the day after ICANN’s contract with the government expires.

Cruz remains worried, however, that something nefarious could be afoot, issuing two press releases just this week on the matter and writing recently that China, Russia and Iran, “will never relent in their pursuit to control the global internet infrastructure.”

Which might be true, if only ICANN wasn’t such an unworthy target.

“There are so many other paths that the Russians or the Chinese could take and have taken to make sure that their citizens or even people around the world can’t see stuff that they don’t want them to see,” Jonathan Zittrain, a law professor at Harvard, told NPR.

Real security threats or not, Cruz and others have also repeatedly referred to the ICANN situation as an “internet surrender” or “internet handover,” stirring, of course, one’s sense of American pride, however small that may be, since, after Saturday, most of us will probably go back to not thinking about ICANN at all.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook