The ‘Brownstone Detective’ Who Digs Up Dirt on New York Homes

Wondering if someone got murdered in your house? Ask Brian Hartig.

A block of Park Slope brownstones, circa 1974. (Photo: Environmental Protection Agency/Public Domain)

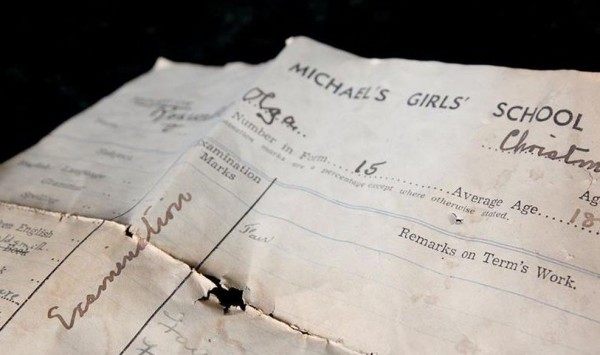

A few years ago, Brian Hartig was deep into renovating his bathroom when something emerged from the wall—a piece of paper, creased in thirds and yellowed with age. Gentle unfolding revealed a report card, dated Christmas 1950, belonging to one Olga Roswell of Michael’s Girls’ School in Barbados. Roswell was great at Shakespeare and needlework, but merely “fair” at grammar, history, and arithmetic. She was a “helpful and reliable” prefect, and whoever was grading her made sure to add good wishes for the future.

For Hartig, reading these marks over 60 years later, Roswell was not just decent at history—she was history, a lively piece of a neighborhood-sized puzzle that he will likely spend the rest of his life putting together. As Brooklyn’s only self-styled “Brownstone Detective,” Hartig takes a unique approach to investigating the borough’s past, diving into it one house at a time.

In 2011, Hartig and his husband renovated their own 1892 brownstone townhouse, on Macon Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant. As the house got fresh fixtures and furnishings, Hartig, who worked at the city’s Department of Homeless Services, developed a new hobby: “At night, I would claw through the debris and find things,” he says.

One week, it was a stack of Victorian-era building blocks. Later, under a trap door in the kitchen, a train operator’s satchel, filled with three decades’ worth of subway cranks and keys. By the time he and his husband had settled in, Hartig says, “I was able to find at least one thing from every family that had lived in the house.”

Victorian-era children’s toys, which Hartig found in the renovation rubble. (Photo: Robin Lester Kenton/Brownstone Detectives)

Soon, his search expanded outward, to nearby libraries, archives, and historical societies. Brooklyn has an endless supply of lives and stories—if you want to delve into its history, it helps to pick an angle. For Hartig, bounding himself within a house’s walls lets him go deep by staying narrow. “I thought, let me see how far I can go! Let me see what information there is out there, in the entire world of information, about one specific house.”

Last October, Hartig left his job as a civil servant and became a full-time “brownstone detective.” Since then, he has spent all of his working hours slowly figuring out what has occurred in and around his clients’ homes. “You’d probably have a heart attack if you knew everything that has gone on,” he says.

It’s a rollercoaster: One building housed Dr. Mary Dixon Jones, the first woman to perform a total hysterectomy. In another, a furniture collector was brutally dismembered, his body parts found frozen in an icy pond near Coney Island.

Brian Hartig and “Aunt Patsy”, who grew up in his house in the 1930s and 40s. (Photo: Brownstone Detectives)

In some cases, keeping up with old neighbors occasionally necessitates tiptoeing around new ones—some of his friends live in the erstwhile home of Martha Place, the first woman to be executed via electric chair. “I haven’t told them—yet,” Hartig says.

Hartig generally starts his searches deep in the city’s archives, thumbing through records in the Department of Finance or the Brooklyn Public Library. Thanks to handwritten property books, gridded with names, dates and prices, he pieces together the “chain of title,” tracing the house’s ownership through the decades.

State and federal censuses give vital stats—names, ages, occupations—but, depending on the year and the census-taker, can also reveal snippets of daily life, such as whether a particular family owned a radio. Newspaper clippings give an idea of the neighborhood ambience. In the late 19th century, for example, Brooklyn was terrorized by mobs of bean-shooters, young boys who roved the streets breaking windows with toy slingshots.

Olga Roswell’s report card, after half a century stuck in a bathroom wall. (Photo: Robin Lester Kenton/Brownstone Detectives)

But Hartig’s most fruitful discoveries come from the descendants of former inhabitants, whom he usually finds on Facebook. Olga Roswell’s hidden report card, for example, was something of a mystery until he met one of her living relatives, Stacey Maupin Torres. According to Torres, their Aunt Caroline, who had lived in the house, was a stickler for proper English. Any mistakes would catch the offender a whack on the head.

“This girl’s mom sent her to the United States to show her aunt, who was a schoolmarm, what kind of a grade she got in grammar,” Hartig says. Olga, hoping to avoid this, must have stashed her report card in the wall somehow—where, over half a century later, it earned oohs and ahhs instead of a smack.

By combining these different types of sleuthing, Hartig comes away with a story—one that might not have emerged through more official channels. “A lot of this history would have just died out,” he says. “I just feel like I’m going back and snatching things from beyond the grave.” Or, more specifically, from behind the bathroom wall.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook