The Duke, the Landscape Architect and the World’s Most Ambitious Attempt to Bring the Cosmos to Earth

Last fall, a hand-picked group of the world’s top theoretical physicists received an invitation to a conference about the multiverse, a subject to which many of them had devoted the majority of their careers. Invitations like these were nothing unusual in their line of work. What was unusual was this conference was not being hosted by a university or research institute, but rather by a Scottish Duke.

And its organizer was not a physicist, but a landscape architect by the name of Charles Jencks.

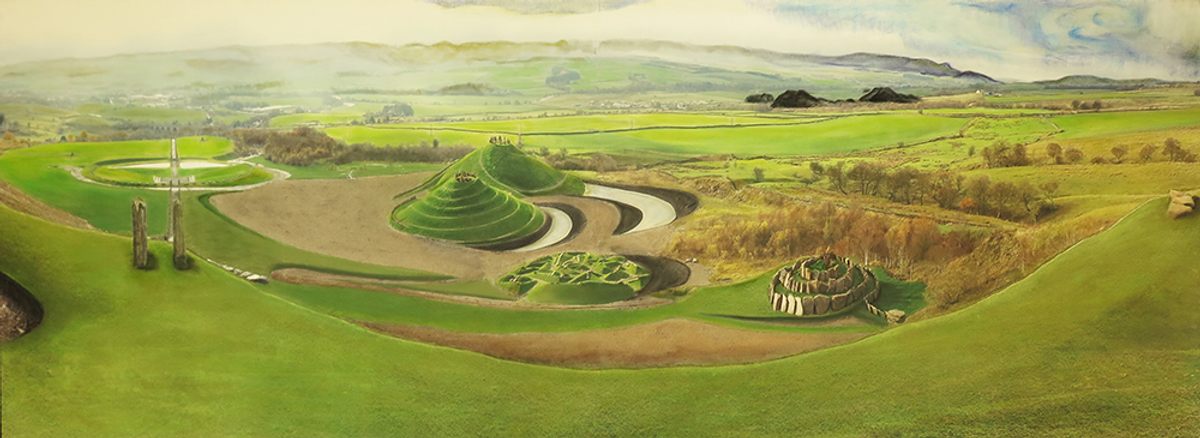

The physicists were surprised to learn that Jencks had spent the past three years bringing their cosmological theories to life in the form of a massive land installation carved into the hills and pastures of the Nith Valley in southwest Scotland. It was titled “Crawick Multiverse” after the village where it was built, and its features, according to the brochure accompanying the invitation, included a Supercluster of Galaxies, twin Milky Way and Andromeda spiral mounds, the Sun Amphitheater (which seats 5,000), a Comet Walk, Black Holes (“in two different phases”), an Omphalos (a boulder-limned grotto symbolizing Earth’s “mythic navel”) and of course, the multiverse itself. And now Jencks, together with the project’s patron, Duke Richard Buccleuch, was asking the physicists to converge on Drumlangrig Castle, to spend the summer solstice weekend discussing the mysteries of the cosmos among Rembrandts and Dutch Masters, and to wander the first earthly representation of the multiverse with a handy, one-page map in their hands.

My father, the cosmologist Alexander Vilenkin, was among the physicists who received this invitation. One could say I’d grown up with the multiverse; my father’s first paper on the subject was published in 1983. He has given lectures around the world, appeared on the covers of magazines, published books and held forth on television about the tumultuous, explosive, eternally expanding state of the cosmos. Multiverse theories suggest a sci-fi scenario: outer space is one giant Etcetera, and ours is but one lonely universe in an endless chorus of universes. In its staggering intricacies and metaphysical implications, it is an idea that seems to test the very limits of human perception. And not all physicists agree it is even true. The notion of fashioning a simulacrum of something so mind-blowingly abstract using nothing more than dirt, rocks and water, sounded, well, frankly insane.

Then I clicked open some photographs Jencks had sent my father. Gazing at a surreal landscape of spiraling mounds and stark plateaus exploding with boulders, it felt as though I were falling through multiple levels of a futuristic video game that hadn’t yet been invented. It was hard to believe these photos had been taken on planet Earth.

When my father asked whether I wanted to come explore the Multiverse with him, there could only be one answer.

top: A view into the world’s first multiverse. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks). above: The North-South view from Amphitheatre of the Crawick Multiverse. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

top: A view into the world’s first multiverse. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks). above: The North-South view from Amphitheatre of the Crawick Multiverse. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

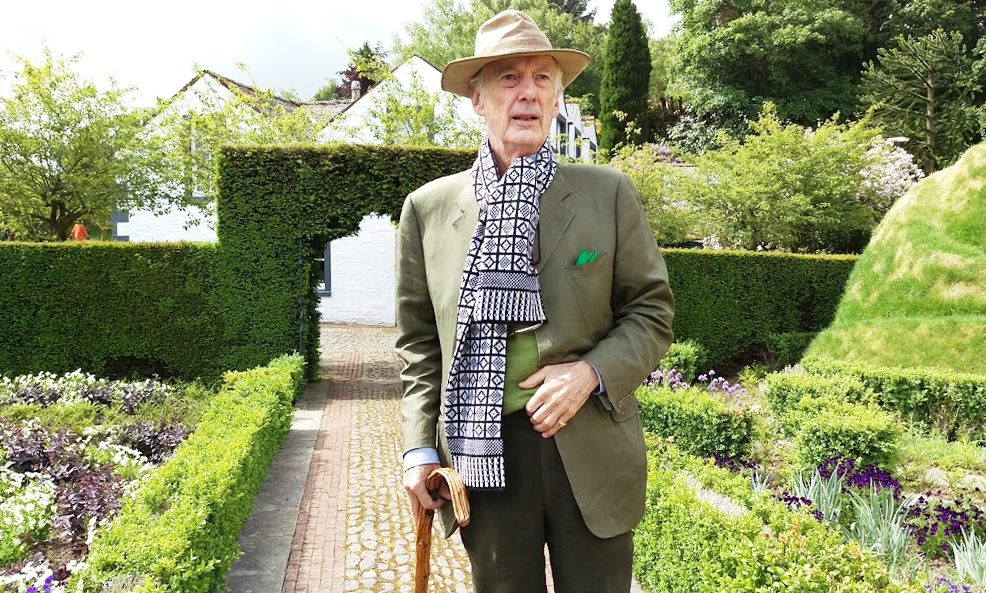

At 76, Jencks is energetic, quick to laugh, and surprisingly stylish. He is tall and thin, and looks all the part of a regal Scotsman, with a scarf tied at the neck, a homburg atop his head, and a carved wooden shillelagh in his right hand. But when he speaks, his American origins (Jencks was born in Baltimore and raised in New England) are betrayed by a flat East Coast accent. Although he does nothing to disguise his old world intellectualism—he is likely to quote Latin or French, or to launch into an explanation of why the anthropic principle is a misnomer, or describe how the epigenetic revolution has doomed neo-Darwinism—his speech is peppered with enabling crutches. “As you know … ,” a typical sentence might begin, or “you’ve probably studied … ,” prods often accompanied by a light touch on the shoulder. Before you can protest that you’ve been miscast as a scholar (or decide he is probably a blowhard) you find yourself giddily swept along, an unwitting co-conspirator in his latest hypothesis—whether you understand that hypothesis or not. The persistent gentility can also make a cipher of the man behind the theories. “I don’t want to go into the thousand and one humiliations because that’s not my nature,” he demurred when asked about dealing with clients who don’t share his scientifically-inspired vision. “I’m happy to struggle. Life is a joyful science.” Given all this, it comes as something of a shock to learn that within the world of architectural criticism where he first made his name, Jencks is known as a firebrand—the flamethrower who burned down the house of modernism.

In 1973, after finishing his Ph.D in Architectural History at University College London, Jencks’ dissertation, Movements in Modern Architecture, was published by Penguin. The modernists, he argued, “had tortured [themselves] into a corner of both criticism, and inability to face what it was discovering about itself,” namely its connection to fascism, both metaphoric — fanatical pursuit of coherence and aesthetic purity—and literal; his research had turned up ingratiating correspondence between Le Corbusier and Mussolini, Walter Gropius and Goebbels, and other modernists jockeying to provide the “new architecture” for the new social order. In subsequent books and articles, Jencks argued that architects should stop trying to purge urban landscapes of manmade disorder one concrete cube at a time, and instead embrace ambiguity, improvisation—the entire chaotic spectrum of emotion that defines the human experience. “It can include ugliness, decay, banality, austerity, without becoming depressing,” Jencks wrote in Movements. “It can confront harsh realities of climate, or politics without suppression. It can articulate a bleak metaphysical view of man…without either evasion or bleakness.” He would later give this bold new inclusive architecture a name: postmodern. It was a term Jencks probably did more to popularize than any other 20th century critic.

My favorite Jencksian metaphor differentiating the old paradigm from the new is cheese-based:

“If the pure Camembert cheese is modern, then the mixed Cambozola is post-modern and the recent crossbreed Camelbert (like Brie but from camel milk) is very pm.”

But not everyone, he soon discovered, was ready for Camelbert. Jencks remembers being escorted out of a Royal Academy Evening to celebrate the Bauhaus to the metronome of “a slow clap;” from architects and critics, and recalls a mysterious incident at Syracuse University where he was “chased off a stage by two dogs.” He claims to have received death threats for touting postmodernism. And while it’s unlikely that Le Corbusier-loving assassins were shadowing his footsteps, it’s true that Jencks had harsh critics. Roger Kimball, the current editor of famed journal The New Criterion, accused him of misrepresenting Modernist master Mies van der Rohe’s connections to the Nazi party and dismissed his post-modernist vision as trendy, arguing he was essentially giving architects carte-blanche to indulge in camp. Such criticism, however, did little to slow Jencks’rising star. He went on to write more books—more than 30 in all—becoming, as Mark Wigley, former dean and current professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, put it, “Mr. Postmodernism himself.”

A panorama painting of Crawick. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

A panorama painting of Crawick. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Jencks’ own career as a landscape architect didn’t begin, as one might expect, as a cerebral experiment, a terra-based test of paper-bound theories. The first garden he designed was born of more primeval causes: love and death. In 1990, Maggie Keswick Jencks, Jencks’ wife, began work on a garden at Portrack House, their 18th-century manor home in Dumfries, Scotland. Keswick was one of the world’s leading experts on Chinese gardens (her book on the subject is still considered a classic). She was experimenting with Feng Shui, and the Taoist idea of harnessing the geological energies hidden in soil and stone, drawing out the “bones of the Earth.” She asked her husband for help—an idea he discouraged at first. “I won’t do it, because I’ll take it over if I do,” Jencks recalled telling her.

Which is exactly what happened, but for reasons both unexpected and tragic. A year after beginning work together on what would become the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, Keswick’s breast cancer, thought to be in remission, returned. As Keswick withdrew (her illness would prove fatal in 1995), Jencks threw himself into work on the garden, developing his singular visual vocabulary—crescent pools, lunar cones, sinuous paths and concentric circles—motifs that he continues to riff off to this day.

The Garden of Cosmic Speculation now ranks among the most famous private gardens in Britain. Although Maggie’s Asian influence remains, over time science has become the garden’s driving metaphor, more specifically, Jencks’ growing obsession with the origins of the universe. According to Tim Richardson, the first landscape critic to visit the Garden in 1996, it’s a passion Jencks has always been eager to pass on to others. “I remember that they were doing jet training exercises,” Richardson recalled of his visit. “I was standing on top of the fractal in the middle of the garden, this huge S-shaped landform, and these jets were flying over the top of us. Charles was in this black suit and an electric blue shirt and matching electric blue handkerchief, and he was talking to me nine-to-the-dozen about all of his cosmological theories. And the jets—I couldn’t hear him—he yelled at me, ‘Can’t you see? We are in a dialog with the universe!’ There was very little I could say to that,” Richardson laughs. “I felt like I was in the middle of the futurist manifesto or something.”

Charles Jencks at his home in Portrack. (Photo: Alina Simone)

Charles Jencks at his home in Portrack. (Photo: Alina Simone)

I had a similar feeling myself touring the garden with Jencks some 20 years later. By then the garden had metastasized into a Dali-esque profusion of scientific metaphors, with Banana Universes and Soliton Waves and Quark Walks and Symmetry Breaks and DNA sculptures so densely entwined that after a half an hour of trying to wreath it all in words, Jencks finally gave up and laughed, “Symbolism run amok!”

The mash-up of science and horticulture may seem like just another hyper-modern hybrid —the landscape equivalent of, well, Camelbert —but it is rooted in a centuries-old tradition. Many of the world’s ancient earthworks are thought to have been astronomical calendars or tools, from the Nazca lines in Peru, to the concentric stone circles of the Rujm el-Hiri in Israel’s Golan Heights. The same holds true for the famous gardens of antiquity, which often incorporated astrolabes and sundials. As Jencks has written, “The idea of the garden as a microcosm of the universe is quite a familiar one…What is a garden if not a celebration of our place in the universe?”

All this might make Jencks sound like a conceptual artist, yet his work has little in common with land artists like Robert Smithson or Andy Goldsworthy, content to let their earthworks decay on an uninhabited spit or anonymous forest floor. To be fully appreciated, Jencks’ work demands both an audience and a skilled phalanx of gardeners. Which is why, in the midst of following Jencks through Portrack, dutifully trying to wring maximum symbolic value from every square inch of terra, a small voice inside my head kept chiming, Can‘t it just be beautiful…? To which Jencks would probably respond: No.

This is probably the biggest challenge of being a Jencks fan. The problem isn’t that he doesn’t understand what he’s talking about, but that he understands too much.

“I think he likes to be one step ahead all the time, to be really candid about it,” Richardson said. “There’s an element where, once you think you understand it, he will always kind of pull it away from you again and tell you another complicating factor.”

Remarkably, Jencks’ efforts to physically inhabit the cosmos actually began 10 years before he began work on the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, with the construction of his own home, a living shrine to theoretical physics which he calls “The Cosmic House,” whose ceilings are covered in murals depicting the birth of the universe. Every room is cosmologically themed down to the “cosmic loo.” Looking up from the toilet-seat vantage point, Jencks explains, one even finds “a white hole” (read: ceiling fan) designed to metaphorically suck away, you know, impurities. Like most things that interest Jencks, he has written a book on the subject (Symbolic Architecture, published by Rizzoli in 1985). In it, he explains that creating the Cosmic House was his way of dealing with “what happens to design and architecture when religion declines.” Science in general, and the cosmos in particular, Jencks concluded, “was what was left after ‘the long withdrawing roar’of religion.”

This conviction has served as the chief animating force behind the landscapes he has spent the last 20 years designing — his career’s spectacular second act. In England, Jencks’ gardens became quite influential, even trendy. For a while in the ‘00s, Richardson said, it became fashionable to have a Jencks spiral mound in one’s garden—a mini Andromeda or Milky Way.

Crawick Multiverse—Omphalos and distant galaxies. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Crawick Multiverse—Omphalos and distant galaxies. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

After the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, Jencks created science-themed gardens throughout Europe and Asia, including work featured in the Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh, Olympic Forest Park in Beijing, and the National Botanic Garden in Dublin. Three years ago he completed The Lady of the North, “the largest landform sculpture in the world” at 46 acres, in Northumberland. From the air, the landscape resembles a reclining woman, but her anatomy, one notices, is made up of the same swirly-hilled nebulas and gravel-pathed comet trails as those found at Crawick. Although there is no mention of science on the Northumberlandia website, when I asked Jencks whether The Lady was also inspired by theories of cosmology, he quickly replied: “Yes.”

Beat. “Women are cosmic.”

The original multiverse was born approximately 13.8 billion years ago from an amniotic stew of “repulsive matter” in an event known as the Big Bang. The multiverse at Crawick had a far humbler genesis.

Until three years ago, it was a wasteland.

Back in the mid-80’s, Duke Richard Buccleuch leased the 55-acre plot to an open-cast mining operation. Soon afterwards, the coal seam ran out, and the owners, lacking the funds to restore the land, simply abandoned the site as it stood. According to John Syme, the councilmember who represents the local ward of Kirkconnel and Kelloholm, the once-bucolic pastureland looked as though “a bomb had been blown up in it.” Decades went by, and the local community grew increasingly unhappy about the eyesore in their midst.

The Garden of Cosmic Speculation: The white steps scissoring down from Portrack House represent the cascading universe. (Photo: Alina Simone)

The Garden of Cosmic Speculation: The white steps scissoring down from Portrack House represent the cascading universe. (Photo: Alina Simone)

But when Duke Richard first approached the Sanquhar Council about cleaning up the abandoned mine at Crawick, it wasn’t to suggest creating a park. Instead, his proposal involved spreading a meter of human waste from a local sewage plant—60,000 tons of treated sludge—across the whole 55-acre site as a means of regenerating the soil. “To say it wasn’t received well,” James Dempster, a Dumfries and Galloway councilmember deadpanned, “is really being quite modest.”

There were obvious reasons to oppose the idea—the smell, as well as the threat of polluting the nearby Nithsdale River. But locals also suspected that the scheme would earn money for the Duke’s estate at the expense of the community. The Scotts no longer reign by hereditary right, but they remain the largest private landholders in all of Scotland. Today Richard, who is the 10th Duke of Buccleuch, serves as the board chair of Buccleuch Ltd., a corporation that serves as “a platform for sustainable economic development” for 220,000 acres of land spread across all of Scotland. A campaign was quickly set up to oppose Scott’s proposal for the Crawick site. Dempster was among those who fought the measure.

It was not long before the Duke abandoned the idea.

Then three years ago, Duke Richard brought Jencks, a friend of more than 40 years, to the top of a windblown hill of coal slag overlooking the mine to discuss restoring the site. It was to be a simple clean-up job: clear away the rubble, level the land, and sort out the wearisome logistics of suds-pond decontamination. But what Jencks envisioned as he looked out from this forlorn ridge surpassed both his expectations and Duke Richard’s. Rising from the broken valley floor, he saw conical hills, undulating landforms and towering stone totems. The mine’s sunken mouth was transformed into an elegant bowl with a jewel-box stage at its heart. Bald earth and blasted boulders were replaced by verdant carpets of pasture grass and serene pools. It was a vision he hoped would serve as an engine of regeneration for a long-impoverished county, and one day, a world-class mecca for art tourism as well.

The original design they presented to the Sanquhar community was austere compared to what Crawick ultimately became, but the suggestion of turning the land into a public attraction was greeted with outsized enthusiasm. “They were literally applauded out of the building,” Dempster recalled. It wasn’t just the low bar set by the prior, human waste-based proposal: Jencks was already well-known for his garden at Portrack; the Duke had committed a million pounds of his own money; and the project would provide a dozen permanent jobs for local townspeople. Still, I was surprised that the idea of a garden dedicated to cosmology didn’t garner any head-scratching.

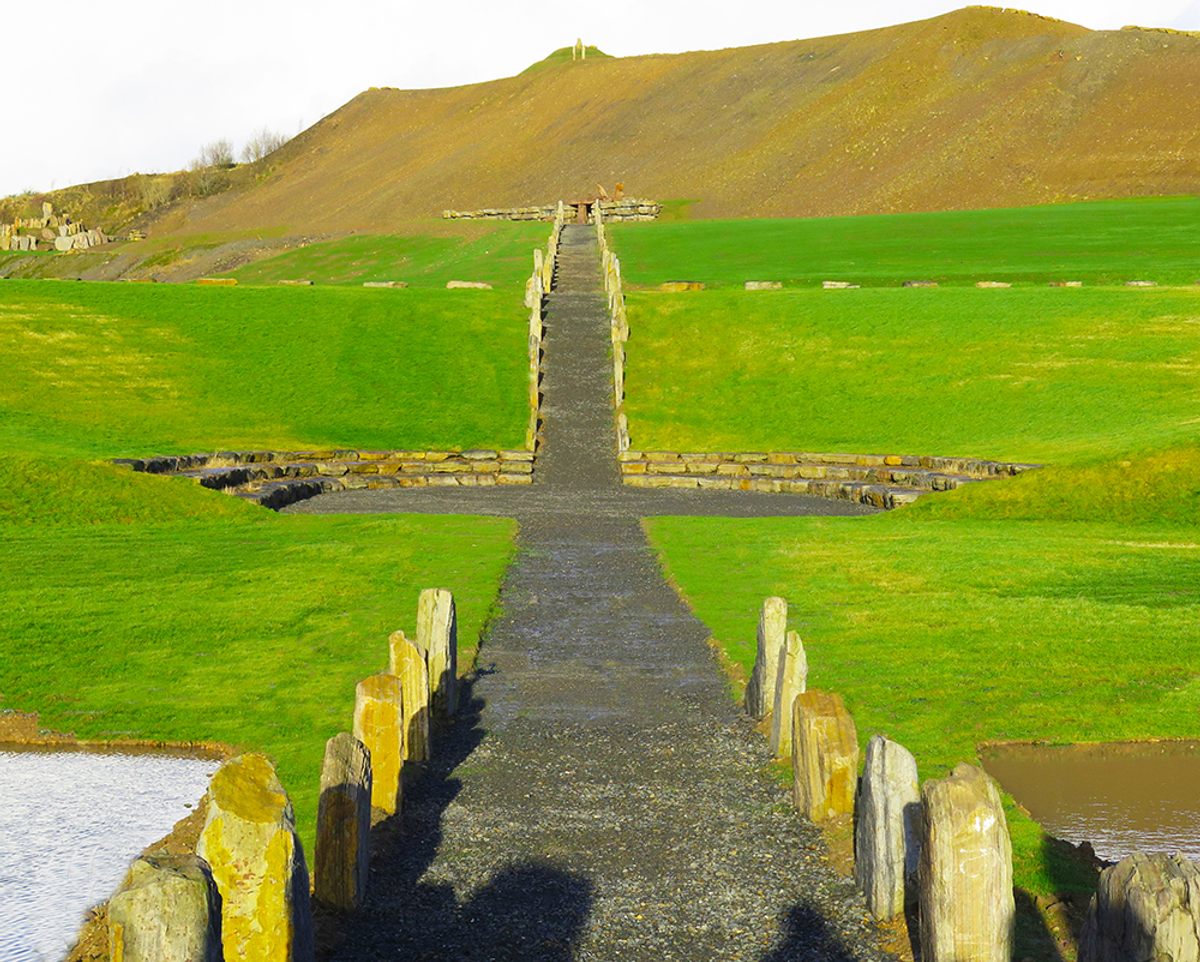

Andromeda view. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Andromeda view. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Cosmology? Demster blinked when I put the question to him. “It was always to be known as ‘Crawick Artland,’ aye. Everybody locally signed up to that. Land art. Land form. Land shape. They liked that.”

To me, it sounded like Jencks had pulled a classic bait-and-switch, promising something fun and easy and swapping in something theoretical and obtuse. But Dempster waved away that concern. People won’t remember it as an “Artland” or a “Multiverse,” he said. Locals wanted a place to take nice walks and hold pipe band competitions. “I’m not a scientist,” Dempster added, “but I’m happy.”

Jencks pointing out one of his iconic spiral mounds, the Andromeda Galaxy, from atop the Northern Ridge. (Photo: Alina Simone)

Jencks pointing out one of his iconic spiral mounds, the Andromeda Galaxy, from atop the Northern Ridge. (Photo: Alina Simone)

So how does one go about building a multiverse? In Jencks’case, it required six men, eight JCB diggers and dump trucks, and three summers. As with all of his projects, this one began with surveys and drawings and Plasticine models, but Jencks soon found himself embracing a more impressionistic approach.

“You know Jackson Pollock? Action painting?,” Jencks said, “Well, this is action sculpture. You have four diggers and four dumpers and they go out in the site and they move it around. You have to design and work as fast as you can think.” Instead of drops of paint, Jencks explained, he used boulders. While the rigorous geometry of Jencks’ landforms, and their effortless concert with one another, suggest serious engagement with CAD, or at least professional survey equipment, the opposite is in fact true.

“I never used any measurements at all,” confirmed Alistair Clark, the master gardener who has been working with Jencks for 56 years and who helped build the Multiverse. “You can measure everything out through the level, you know, spot on. But it might not look right. I just found it much easier to trust my eye.”

In other words, Jencks created his massive paean to physics by … winging it.

Which in part explains how the project metastasized from an “artland”into a “multiverse.” One that Jencks intends to devote the rest of his life to infinitely expanding, embellishing it with ever deeper and richer strata of detail. “It’s the first multiverse in the universe,” Jencks explained, “and I’d like to make it the one to surpass.”

A map of the Crawick Multiverse. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

A map of the Crawick Multiverse. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

The driver who picked me up in Edinburgh to bring me to Crawick was a 34-year-old man named Stuart. His home was in Dumfries, 30 miles away from the Multiverse, but he had lived for some years in the neighboring town of Kirkconnel, which he described as a place where “not much happens.” And as we drove beyond the exurbs of Edinburgh, indeed, the landscape underwent a noticeable transformation. Rolling hills, crosshatched by ancient stone fences, stretched unbroken to the horizon. There were few houses and fewer people—only black and white sheep scattered across the green hills like dice on a craps table. As we drew closer, the road narrowed, the sheep dwindled and the peaks surrounding us grew ever more stark and stony. “You know, there’s gold in those hills,” Stuart said, nodding to the bald escarpment to our right. I thought he was being facetious, quoting the old adage, but it was a statement of fact: 10 days prior, a Canadian tourist had turned up a record-breaking 20 carat nugget at the gold panning course up at the Wanlockhead Museum of Lead Mining.

But unlike Wanlockhead, whose mineral wealth earned it the nickname “God’s Treasure House,” Crawick Village, and its larger neighboring town of Sanquhar, haven’t known a proper boom since the mid-1880s when they were the center of Scottish wool production. After the Industrial Revolution shuttered Crawick’s carpet factory, came the discovery of black gold: coal. While long mined throughout the Upper Nithsdale Valley, coal didn’t become the backbone of the local economy until well into the 20th century, but even that relative prosperity proved short-lived; many of the coal seams were shallow and soon exhausted, leaving the landscape pocked with “coal bings,” eerie pyramids of carbon spoil. By 1971, the Glasgow Herald was calling the Sanquhar district one of Scotland’s unemployment “black spots.” The open cast mine at Crawick, now home to Jencks’ Multiverse, was the last to close.

In attempting to dial back a decline that’s been ongoing for more than 150 years, the Duke and Jencks have their challenge cut out for them. The very road to Crawick seems to mock tourism, winding as it does through serpentine valleys where fences do little to discourage curious livestock from staring down cars from the middle of the road. Coming from Glasgow the only route to Crawick narrows at the juncture of a 13th century tollbooth, to accommodate only one car at a time. It’s not so much a question of, “if they built it, will they come?”—the Lady of the North in Northumberland attracts 115,000 visitors a year, and during the one day each year when Jencks’ Garden of Cosmic Speculation is open to the public in nearby Dumfries, up to 4,000 cars jam the roads—but how, exactly, will they get there. Although the amphitheater Jencks built can accommodate 5,000, the Multiverse parking lot can only fit about 75 cars, which means you can’t just show up at Crawick, you need to make an online reservation first. All of this pretty much banishes visions of EDM festivals and mobbed gift shops.

Andromeda detail. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Andromeda detail. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

But take a flyover view of the Scottish lowlands and a different picture emerges, of a “cosmic route” as Jencks puts it, connecting the Multiverse and Drumlanrig Castle—with its formal gardens and world-class land art—to the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, and further away, Little Sparta, perhaps Scotland’s most celebrated garden, and Jupiter Artland, home to Jencks ‘biology-themed “Cells of Life” landforms. Is it fantastical to think these gardens might form a processional route for art pilgrims? Only two hours drive from Scotland’s capital city, Crawick certainly doesn’t need as much help as, say Marfa, Texas—the minimalist art mecca located in the drought-plagued Chihuahuan Desert of west Texas. When Donald Judd screwed his first fluorescent light tube into a hangar wall in 1971, few would have anticipated that Marfa (whose population, like Sanquhar’s, hovers near 2,000) would one day host a museum of contemporary art, a multifunctional art space, a fake Prada store and ironic dining options such as the Food Shark Museum of Electronic Wonders and Late Night Grilled Cheese Parlour, to become, as NPR put it, a land of “vegan food, straw bale houses, and funky bars filled with artsy kids clinking Shiner Bocks with famous painters and film directors.”

There are many, of course, who think Judd would be turning over in his grave if he could see Marfa now, and Jencks himself is horrified by the notion of Crawick transforming into some kind of “Mickey Mouse, American thing.” No doubt the hoped-for renaissance here would take a different form, but the essential point remains: transformation is always possible.

On the morning of the summer solstice, after a breakfast of baked eggs, roasted tomatoes and ham at Drumlanrig Castle, the physicists boarded a blue shuttle bus for the Multiverse. The scientists who accepted Jencks’invitation were a less august group than had originally been expected (there was some noticeable grumbling amongst the press corps on this point), yet still included enough stars to power a NOVA special. The bus carried them down a long, winding drive painted crimson, past stone cottages that might have been dropped straight from the Brothers Grimm, and beyond an endless row of SUVs queuing up for a different event hosted at Drumlanrig that weekend: Tough Mudder, a 10-mile obstacle course and endurance race promising to turn this “fairytale castle into your worst nightmare.”

Black Hole painting. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Black Hole painting. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

While each of the scientists came for their own reasons, they shared a common curiosity. How would Crawick’s multiverse compare to the one they had spent their lives envisioning? Despite the earthbound constraints, had Jencks managed to capture the grandeur of the cosmos? Did he get it, you know, right?

Earlier that week, the Duke had sent an email warning that the forecast promised wind and lashing rain. Although it was mid-June, the temperature in Sanquhar hovered in the mid-50s. So when the van pulled up at the foot of the Andromeda Galaxy, the physicists disembarked swathed in coats and scarves, hats and boots. A few carried oversized umbrellas. Only the Duke, in a checkered shirt and slouchy corduroys, seemed unbothered by the weather as he passed around walking maps. Though Jencks gave cosmology top billing at Crawick, the Multiverse was actually a mashup of disciplines (physics, astronomy, religion), as well as styles (Neolithic, Romantic, Postmodern) that managed to combine the austerity of a Japanese rock garden with the whimsy of an Alexander Calder mobile; an improbable marriage of Seussian shapes and GPS precision. It was also still a construction site. The muddy plateau abutting the Supercluster bore the telltale tracks of excavators and dump trucks, and the grotto where the Omphalos was housed remained locked, Duke Richard explained, “because it had failed health and safety.”

Galaxies in the Crawick Multiverse. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Galaxies in the Crawick Multiverse. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

The party made its way up a steep dirt road along the naked ridge to the Northpoint Shelter. Two years from now, the sheer slope will teem with nettles, thistle, sticky willy, cow’s grass and wildflowers, but today the ground was still mostly bald, the grass patchy. The group ooohed, training their cameras on the twin hills of Andromeda and the Milky Way to their right, rising like pistachio soft serve into a cloud of marshmallow fluff. Then they turned to the left, no less enthralled by the sheep and cows grazing in the adjoining pasture.

The physicists fractured into groups. Some wandered the perimeter of the downward spiraling Void Shelter, punctuated at the bottom by an apostrophe-shaped pool of murky water. Others sandwiched themselves between two flat-sided boulders where one could look straight down at a grande allée of boulders, a quarter-mile path that ran straight through the elegant bowl of the sun amphitheater, cleaving the pool beyond into twin halves. Meanwhile, above their heads, on conical spire called the “Belvedere Finger,” Charles Jencks held forth to a film crew from BBC Arts, an enormous furry microphone hovering over his head like some Jurassic moth.

From the North Point, we made our way down the comet walk—journey of perhaps five city blocks slowed by the rough terrain—where I caught up with Lord Martin Rees, an astrophysicist and cosmologist currently serving as the 15th Royal Astronomer.

The Multiverse is surrounded by grazing pastures, which makes for a stunning contrast from its highest point. (Photo: Alina Simone)

The Multiverse is surrounded by grazing pastures, which makes for a stunning contrast from its highest point. (Photo: Alina Simone)

“It’s a speculation which may be true,” Rees mused about the multiverse. “I like to think of it as a new Copernican Revolution. We’ve learned that the Earth’s not the center of the solar system. We learned that our solar system is one of zillions of planetary systems in our galaxy. We’ve learned that our galaxy is one of zillions of galaxies in the visible universe. But we’ve learned now that possibly, our visible universe, huge though it is, is just a tiny part of physical reality. And there may have been other big bangs leading to other cosmoses perhaps quite different from ours.” We took a sharp right, approaching a spot marked “comet explosion” on our maps, which in non-cosmological terms resembled an impressive cluster of boulders.

Rees, who is 73, leaned on his cane and paused, taking it all in. “This wonderful earthworks here is a sort of metaphor for all of this,” he smiled. Of course it wasn’t a very precise representation, he added, and there were ways in which it could be improved, but as a “happening of instruction”and an artwork that sought to represent the complexity of the cosmos, it was still, Rees stopped, searching for the right words, “great fun.”

The Multiverse itself turned out to be about the size of a swimming pool, an upward-spiraling mound lined with red sandstone and mudstone boulders. At its base, I found my father and his friend Bernard Carr, a professor of mathematics and astronomy at Queen Mary University.

“I’ve spent so many years thinking about it but this is the first time I’ve actually entered it,” said Carr, before quickly correcting himself, “Of course, we’re all in the multiverse.”

The North-South Line. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

The North-South Line. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

We had just begun our ascent when he stopped to peer at a carving on one of the boulders. “It could be the burgeoning complexity of life. I don’t know… I mean, it’s interesting. It’s like a giant fan, isn’t it?”

“Symmetry breaking,” my father added, leaning in.

“This is rather like in quantum cosmology where you have a superposition. All possible histories of the universe.” Staring at the carving, Carr realized he actually has a lecture slide that looked quite similar to it, which led to the conjecture that the carved stones encircling the Multiverse functioned like a Neolithic PowerPoint presentation.

“Makes you wonder what a Neolithic seminar would have been like before PowerPoint,” Carr laughed. “Bring your own stone!”

We wound our way up the path, stopping periodically to puzzle over Jencks’ cosmological hieroglyphics, until we reached the top, where we crowded around the unfinished altarpiece, a red sandstone boulder with a design still outlined in graphite, mysteriously captioned “Hot Stretch.”

“Hot stretch. Alex, this is you.” Carr turned to my father, who stepped forward for a better look. He peered at the stone for a long moment.

“The wave function of the universe?” he offered.

“Ah, that makes sense!”

Carr had spent so much time unpacking the Multiverse that he’d forgotten to take any pictures of it. Now he held up his cell phone and took a step back, only to teeter perilously on the edge of the summit’s steep ridge.

“Oh the irony if I were to fall off this thing,” Carr laughed. “Slain by the multiverse!”

It was, the physicists agreed, the ultimate doomsday scenario.

A local pipe band makes its way across a field that still bears the marks of construction prior to the opening ceremony. (Photo: Alina Simone)

A local pipe band makes its way across a field that still bears the marks of construction prior to the opening ceremony. (Photo: Alina Simone)

The day before the Multiverse was to be officially unveiled—the day that also happened to be Jencks’ birthday—Duke Richard hosted a soft opening for members of the community. It was cold and wet, but that didn’t deter hundreds of locals from filling the muddy parking lot, crunching up the long, gravel walk, and making the place their own. There were school children and town officials and engineers in fluorescent orange jumpsuits. There were five locals dressed as space aliens carrying giant tinfoil stars and a spacecraft fashioned out of paper mache, whose only purpose was to lend an extra-terrestrial element to what was already a very otherworldly event. Atop the twin spires of the Andromeda and Milky Way Galaxies the eerie call-and-response of bagpipe players echoed across the valley. I watched four siblings race one another up to the top of the Multiverse’s spire as their mother, standing at the base, tried to maneuver a cell phone around the fifth child strapped to her chest. Over by the East Comet Collision Shelter, a local group was practicing Tai Chi, cutting slow motion circles in the air.

Speeches were made in the Sun Amphitheater. Duke Richard thanked Jencks and his engineers for creating “a landmark whose fame will extend far beyond Scotland.” Councilmember John Syme declared the Multiverse had, quite improbably, turned him into an art lover. Charles Jencks called it the happiest day of his life. Then the schoolchildren sang, and a pipe band played, and two girls on raised platforms kicked out an enthusiastic Highland Fling.

Locals dressed up as extraterrestrials for the Multiverse’s opening ceremony. (Photo: Alina Simone)

Locals dressed up as extraterrestrials for the Multiverse’s opening ceremony. (Photo: Alina Simone)

Throughout all of these festivities, I noticed there had had been no talk of black holes or galactic superclusters. Jencks has insisted that he didn’t want to turn Crawick into a lesson in physics, but that he hoped the experience might serve as a subtle form of cosmological consciousness-raising. To see whether this was true, I decided to talk to some locals. Mary Crichton and her daughter Pamela, the pair seated on the stone benches next to me, had both lived in Sanquhar their entire lives.

“Oh I think it’s gorgeous. Very, very nice.” Mary said. “Picturesque.”

“Before it was all a mess,” Pamela seconded.

“Trees and rubble.”

“But does the place remind you of anything…?” I asked.

“The Stone Age,” Pamela laughed.

Maybe it also made them think of something else, I nudged. Like…cosmology?

Mary eyed me silently. “I’m just enjoying the moment,” she said, which I took as my cue to leave. Seeing me looking disconsolately around, Duke Richard swooped in and ushered me over to Jamie Shankly, a costumed young man sitting atop a horse with an elaborately braided mane. In addition to being a psychology student at the local university, Jamie was Sanquhar’s principal cornet, which meant he led the annual Riding of the Marshes, a Scottish tradition that dates back to at least the 1500s, when any man who owned a horse was called upon to inspect the borders of their burgh, ensuring no encroachments had been made.

Andromeda view. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Andromeda view. (Photo: Courtesy Charles Jencks)

Craning my neck upwards, I ask Jamie what he thought of the Multiverse. “They did a good job cleaning it up,”he nodded enthusiastically. “It’s certainly pleasing to the eye.”

“It’s actually inspired by cosmology. The, uh, theories of abstract physics … ” I trailed off, realizing the three days I’d spent in the Multiverse hadn’t done much to improve my ability to describe it.

“Oh?” Jamie’s eye widened. From atop 500 years of Scottish history, he gazed out at the elegant forms blooming across the valley, iconic shapes whose simplicity cloaked 14 billion years of evolution, synthesis and synergy.

“Yeah,” he smiled, nodding slowly. “I can kind of see that.”

This story was funded with support by Longreads Members. Join, or make a one-time contribution.

Update, 9/15: The original version of this story misstated Martin Rees’ age. We regret the error.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook