Double Sunsets and Peasants with Pitchforks in the Trials of 18th Century Balloonists

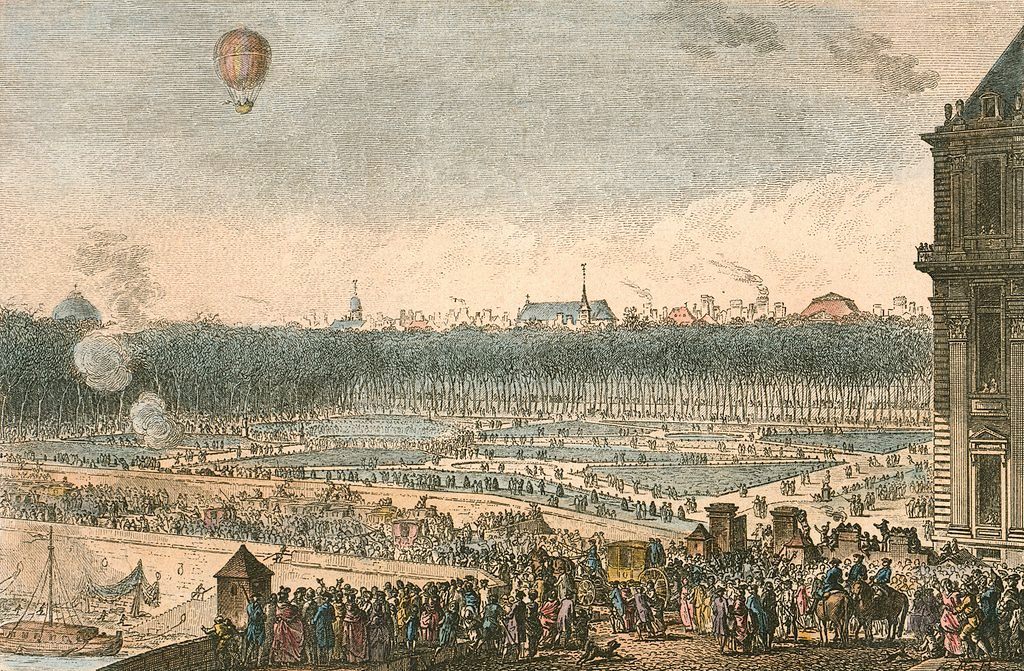

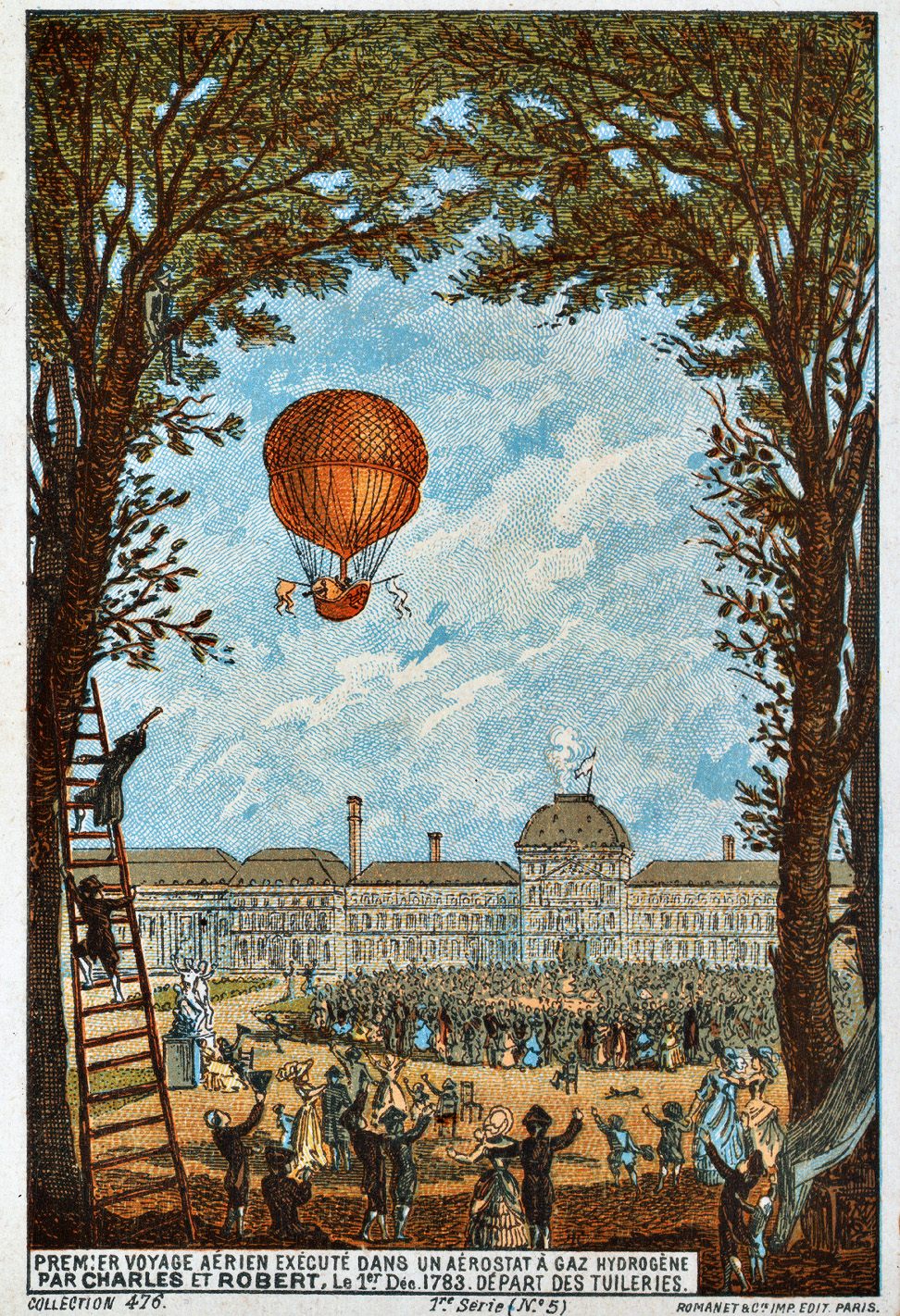

The Jardin des Tuileries depicted during the balloon launch (hand-colored etching, 1783) (via Library of Congress)

The Jardin des Tuileries depicted during the balloon launch (hand-colored etching, 1783) (via Library of Congress)

1783 was a big year for ballooning, one with peasants attacking the strange flying machines with pitchforks, and of double sunsets. Perhaps the most monumental achievement was on December 1, when French scientist Jacques Charles with Nicolas-Louis Robert of les Frères Robert, a duo of ballooning brothers, ascended into the skies over Paris in the first manned hydrogen balloon flight.

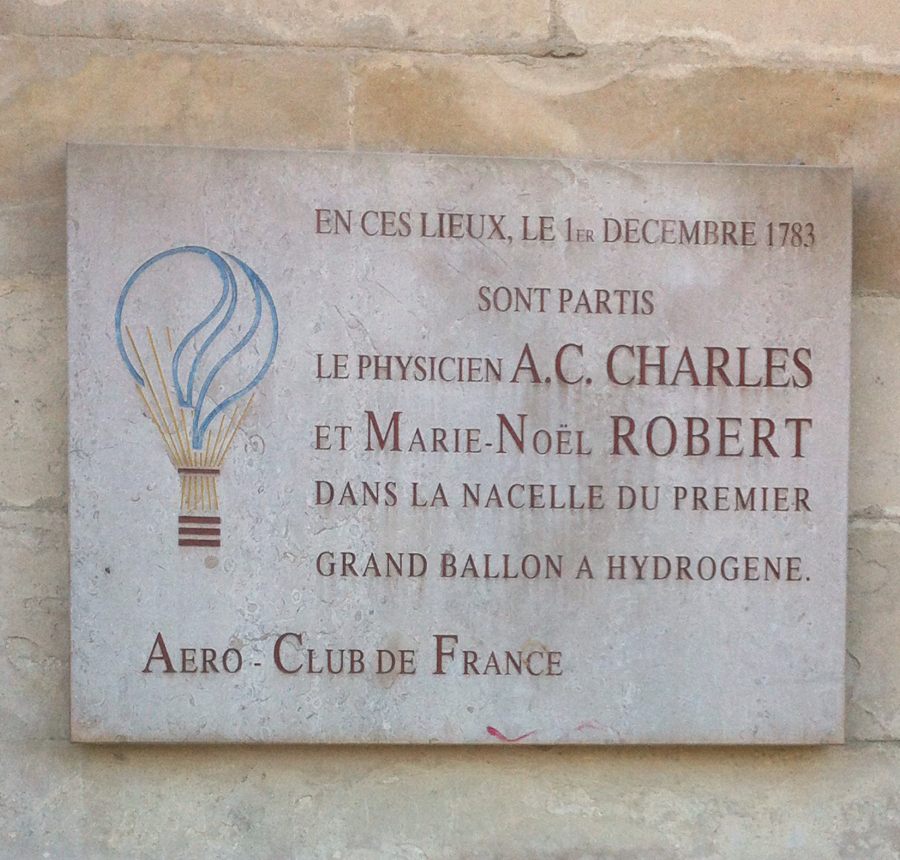

Plaque for the December 1 flight in the Jardin des Tuileries (photograph by the author)

Plaque for the December 1 flight in the Jardin des Tuileries (photograph by the author)

A small plaque for the flight is tucked in an alcove at the entrance to the Jardin des Tuileries just before the garden meets with the busy Place de la Concorde. Despite being wedged on the thoroughfare between two of the most touristy destinations in Paris — the Louvre and the Champs-Elysées — the marker mostly goes unnoticed. However, back on that day in 1783, some 400,000 people packed into the garden just for the event, about half the population of the whole city at the time.

Jacques Charles with Nicolas-Louis Robert (whose name is commemorated with his alternative name “Marie-Noël” on the plaque) didn’t just suddenly decide to go ballooning, there was a whole aeronautical history that brought them to that point. Robert with his brother Anne-Jean (whose parents must have been wanting daughters based on the names) were active balloonists. Charles, however, had delved into physics without much training and was much more of an experimenter in the field.

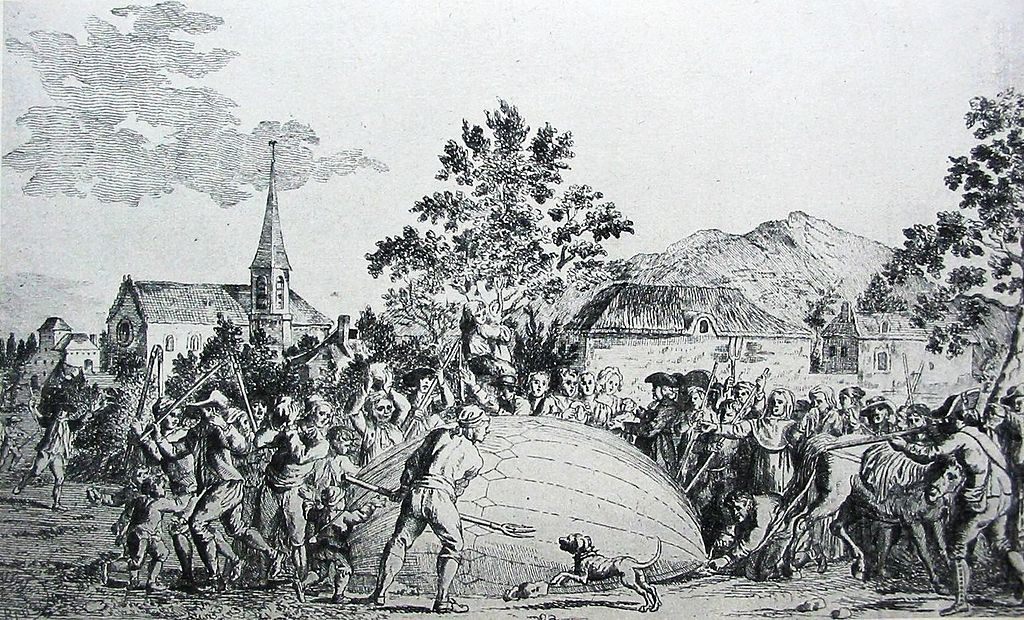

Earlier that year, on August 27, the group had launched another hydrogen balloon, this one unmanned. The balloon left the Champ de Mars in Paris (future home of the Eiffel Tower) and touched down in the village of Gonesse. There the locals were thrown into terror by the silk and rubber object suddenly drifting down from the skies like an otherworldly invasion, and thus rendered it to shreds with knives and pitchforks.

Gonesse villagers attacking the balloon (via Wikimedia)

Gonesse villagers attacking the balloon (via Wikimedia)

Then on September 19, another balloonist, Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier, part of another ballooning brotherhood with his sibling Joseph-Michel, launched a balloon for King Louis XVI. The feat would not just get their father a title of nobility, but was the first to carry living creatures, with its passengers being a duck, a rooster, and a sheep. They survived, and the sheep was given a place of honor in the menagerie of Marie-Antoionette (no word on the fowl, perhaps there was a celebratory feast to which they fell victim). On November 21, at the Muette castle, Jean-Francois Pilâtre de Rozier then claimed the title as the first person to go up in a hydrogen balloon, while it remained tethered to the ground.

Crowd trying to scale the Jardin des Tuileries wall to see the balloons (note the men viewing the women’s exposed rears with their spyglasses instead of the launch) (via Library of Congress)

Crowd trying to scale the Jardin des Tuileries wall to see the balloons (note the men viewing the women’s exposed rears with their spyglasses instead of the launch) (via Library of Congress)

The scene was insane on December 1, the country hyped up by the growing aeronautical feats. Contemporary artists delighted in depicting the wonder and madness, such as the above cartoon with men turning their spyglasses to the exposed bottoms of women attempting to climb the Jardin des Tuileries wall. The balloon itself was processed in by four noblemen, and in the crowd was Benjamin Franklin.

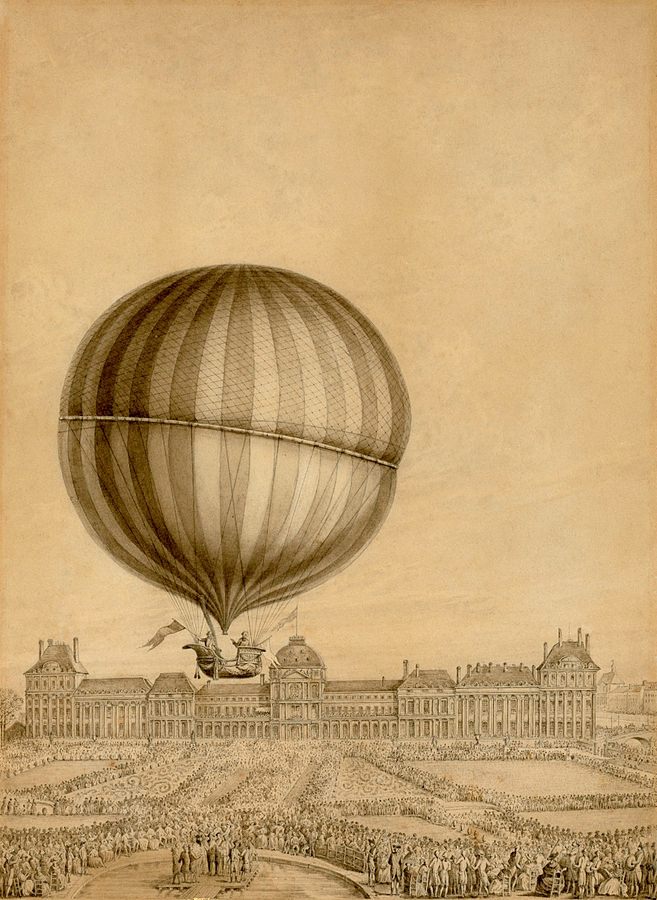

When the balloon soared to the skies, Charles was absolutely euphoric. As Richard Holmes quotes in his book Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air, the scientist wrote of the journey:

“Nothing will ever quite equal that moment of total hilarity that filled my body at the moment of take-off. I felt we were flying away from the Earth and all its troubles and persecutions for ever. It was not mere delight. It was a sort of physical rapture […] I exclaimed to my companion Monsier Robert - ‘I’m finished with the Earth. From now on our place is in the sky!’”

Illustration of the balloon flight by Antoine Sergent dit Sergent-Marceau (1783) (via Library of Congress)

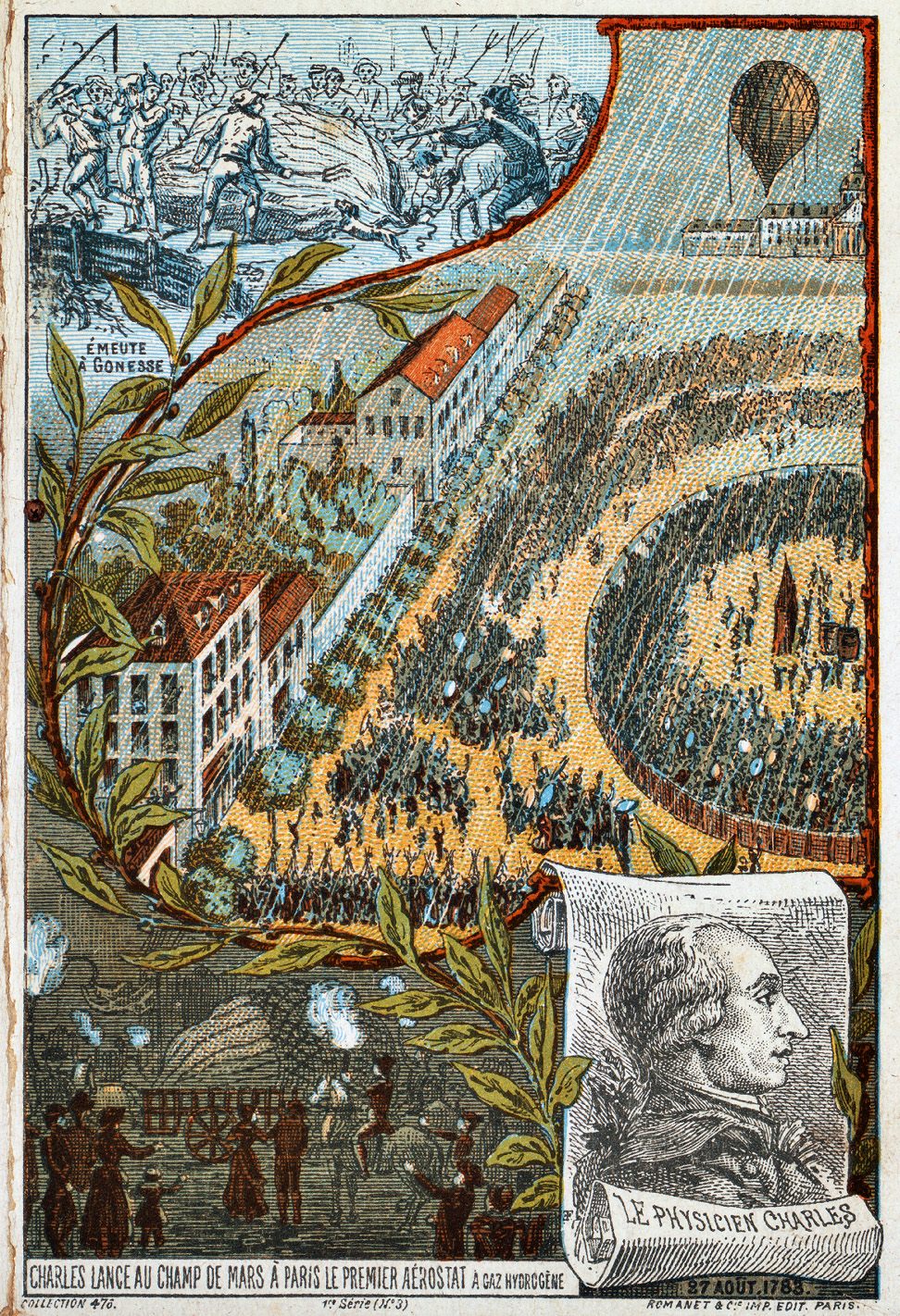

Chromolithograph of the flight (1890-1900) (note the destruction of the earlier balloon by the peasants in the upper left corner) (via Library of Congress)

However, despite his avowal to leave all the annoyances of the planet behind, the day would be Charles’ last in a balloon. After landing at Nesles-la-Vallée, brought down by horseback chasers led by the Duc de Chartres, Charles took a solo flight. The balloon wasn’t quite in launch shape, and he took off much quicker than expected. As a contemporary account goes:

“In this second journey M. Charles experienced a violent pain in his right ear and jaw, no doubt produced by the rapidity of the ascent. He also witnessed the phenomenon of a double sunset on the same day; for, when he ascended, the sun had set in the valleys, and as he mounted he saw it rise again, and set a second time as he descended.”

Chromolithograph of the flight (1890-1900) (via Library of Congress)

The dedication of the plaque in the Jardin des Tuileries in 1914 by the Aéro-Club de France (via Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Just two years later, balloonists Joseph Croce-Spinelli and Théodore Sivel would perish attempting to fly higher than anyone before, reaching 28,000 feet on April 15, 1785, but unfortunately dying in the process. (They are buried in Père-Lachaise, a monument showing their corpses hand-in-hand.) Ballooning was really one of the last hurrahs of the French aristocracy, a show of richness and wonder above people who were starving. However, in these moments were real scientific victories that would lay the groundwork for the next century of flight experimentation, and eventually make leaving the ground with its troubles something attainable for the masses.

Print of the Tuileries balloon launch (one scientist seeming to have dropped his flag of victory) (1783) (via Library of Congress)

The plaque in the Jardin des Tuileries (photograph by Jim Linwood)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook