The Forgotten Secret Language of Gay Men

After a heyday in the ’50s and ’60s, Polari all but vanished.

The Manchester Pride parade. (Photo: Pete Birkinshaw/CC BY 2.0)

These days, very few people know what it means to vada a chicken’s dolly eek.

Vada (“look at”), dolly eek (a pretty face), and chicken (a young guy) are all words from the lexicon of Polari, a secret language used by gay men in Britain at a time when homosexuality was illegal. Following a rapid decline in the 1970s, Polari has all but disappeared. But recently it’s been popping up again, even appearing in the lyrics of a song on David Bowie’s final album.

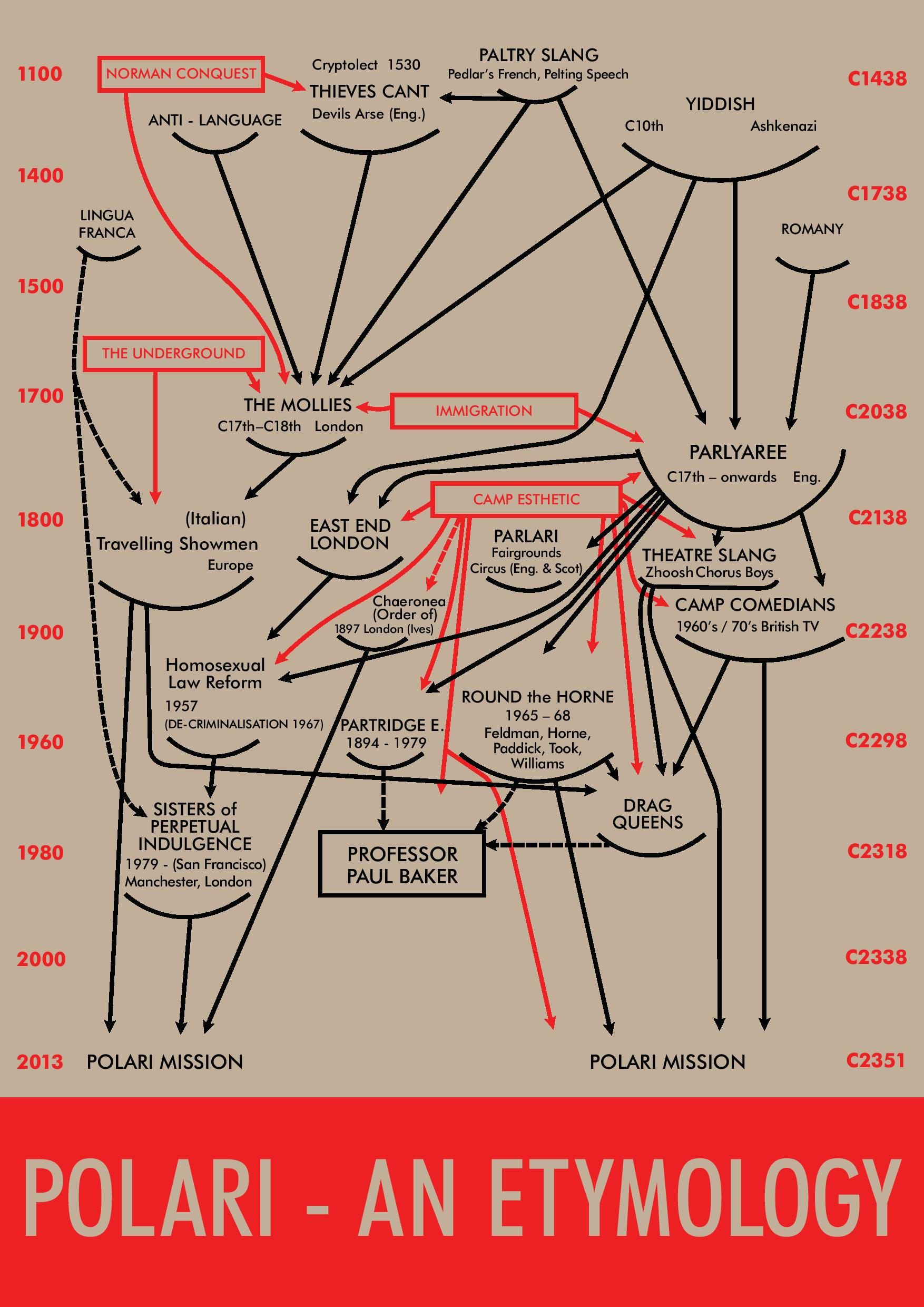

Polari is a language of, in linguistic professor Paul Baker’s words, “fast put-downs, ironic self-parody and theatrical exaggeration.” Its vocabulary is derived from a mishmash of Italian, Romani, Yiddish, Cockney rhyming slang, backslang—as in riah to mean “hair”—and cant, a language used by 18th-century traveling performers, criminals, and carnival workers. Many of the words are sexual, anatomical, or euphemisms for police.

Historically, people who spoke Polari “were generally ‘the oppressed,’ the bottom of the rung,” says Jez Dolan, a Manchester artist whose work focuses on queer culture. “Polari is very much a working-class thing.” During the 19th- and early 20th centuries, the language was used by merchant seafarers and people who frequented the pubs around London’s docks. In the 1930s it was spoken among the theater types of the West End, from which it crossed over to the city’s gay pubs, gaining its status as the secret language of gay men.

Jez Dolan’s Polari - an Etymology According to a Diagrammatic by Alfred H. Barr (1936), which he offers with the caveat that it’s likely “full of holes and assumptions and bare-faced lies.” (Image courtesy of Jez Dolan)

In England, homosexuality was officially considered a crime until 1967, when the Sexual Offences Act legalized private “homosexual acts” between consenting adults over 21. (“Private” was interpreted very strictly by the courts—hotel rooms, for example, did not qualify.) The Act came a decade after the government’s Wolfenden Report, which ignited debate by recommending the partial decriminalization of homosexual acts.

During these interim years, when being openly non-straight brought the risks of social isolation and criminal prosecution, Polari provided gay men with a subtle way to find one another for companionship and sex. Says Dolan, “if you fancied somebody you’d drop a few words in, see if they picked it up, and go from there.” The code words of Polari, indecipherable to outsiders, made the solicitation process safer, allowing men to approach potential partners without having to reveal their own sexuality.

Among confirmed gay men, however, there was nothing subtle about Polari conversations. The language was used to “recount stories of trade [sex], and cottaging [looking for sex in public bathrooms], and wigs and makeup and who was wearing what and who did what to whom,” says Dolan. “It was a way of showing off and bitching and all that kind of stuff.” In Hello Sailor! The Hidden History of Gay Life at Sea, Paul Baker and Jo Stanley write that Polari played a role in “allowing gay men to construct a humorously performative identity for themselves.”

This “performative identity” was heavy on camp—the word camp itself comes from Polari. Here lay its great virtue and its great problem. In the late ‘60s, as gay liberation groups were fighting for recognition and equality, Polari hit mainstream British pop-culture in the form of Julian and Sandy, two flamboyant, not-officially-but-pretty-obviously gay characters on a BBC radio show called Round the Horne. Julian once delivered a rousing speech culminating in the words: “Let us put our best lallie forward and with our eeks shining with hope, troll together towards the fantabulosa futurette!”

Round the Horne was enormously popular. Every Sunday at 2:30pm, around nine million Britons tuned in to hear the latest exploits of the unflappable Kenneth Horne and the madcap personages that whirled around him. And Julian and Sandy were the most madcap of them all. Portrayed as two out-of-work actors launching a series of doomed business ventures, Julian and Sandy had effeminate voices, spoke in Polari and threw in frequent sexual innuendo. If they appeared on TV in 2016, they would be instantly denounced as offensive stereotypes. But in the ‘60s, they were the extent of gay men’s media representation in Britain.

Julian and Sandy presented a conundrum: as lovable gay characters on a very popular show, they endeared themselves to British audiences in an era of homophobia. But some gay liberation groups came to resent the image that they—and Polari—perpetuated. By the early ‘70s, as LGBT groups fought for rights beyond those granted by the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, the image of the camp gay man had become the target of ire. Many who were lobbying for sexual equality, says Dolan, “felt it was about gay people presenting themselves as just ordinary folks.” As a result, “anything that smacked of camp had to be thrown out the window”—including Polari.

The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, a ”leading-edge Order of queer nuns,” have used Polari in their ceremonies. (Photo: torbakhopper/CC BY-ND 2.0)

These days, Polari is little-known. “There’s very few people who actually use it anymore,” says Dolan. “Gay men under 40 barely know of it at all.” In the last few years, however, the underground language has resurfaced. In 2012, Dolan and Joseph Richardson launched the Polari Mission, a Manchester-based project that incorporated a Polari dictionary app and lectures about the history of the language. It also incorporated a Polari version of the King James Bible translated by Tim Greer-Jackson, a computer scientist who is part of an order of queer nuns called the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

In 2015, Karl Eccleston and Brian Fairbairn made the short film Putting on the Dish, in which the characters speak entirely in Polari. Set in 1962, it involves two men meeting on a park bench and having a highly coded conversation. In the script, the characters are named Maureen and Roberta, a reference to Polari speakers’ tendency to feminize male names.

When Eccleston and Fairbairn posted the film online, they were surprised by the enthusiastic response—and the level of fascination with Polari, this mysterious, indecipherable “gay language.” But though Polari has faded, similar languages are still being used. “These kinds of cants still exist where oppression is still entrenched,” says Eccleston, citing Swardspeak, a language based on English and Tagalog that is used among gay men in the Philippines.

Given its associations with stereotypical representations of gay men, Polari may not seem to have a place in the 21st century. But the backlash against camp has mellowed—it’s not the way to be gay, but it’s one way among many. Dolan brings up the point that gay men shouldn’t have to be “straight-acting” in order to be accepted: “Might it not be more fun to embrace a bit more camp and actually have fun with ourselves and with each other?”

“If we’re not having a backlash against stereotypical camp behavior in the media, we’re having a backlash the other way, where it’s stereotypical butch behavior,” says Fairbairn. “I think that will be a never-ending back and forth.”

Polari may not come back into conversational use, but it ought to be preserved, says Dolan, because it’s “a significant piece of British queer history” that, while mostly forgotten, has its own appeal to younger generations. “I’ve worked with young people’s LGBT groups,” says Dolan, “and when you say ‘We’ve got a language,’ they’re like, ‘No, really? We’ve got a language? Oh my God, how exciting is that?’”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook