The Ghost Of Bruce Wayne’s Real-Life Namesake Haunts Pennsylvania

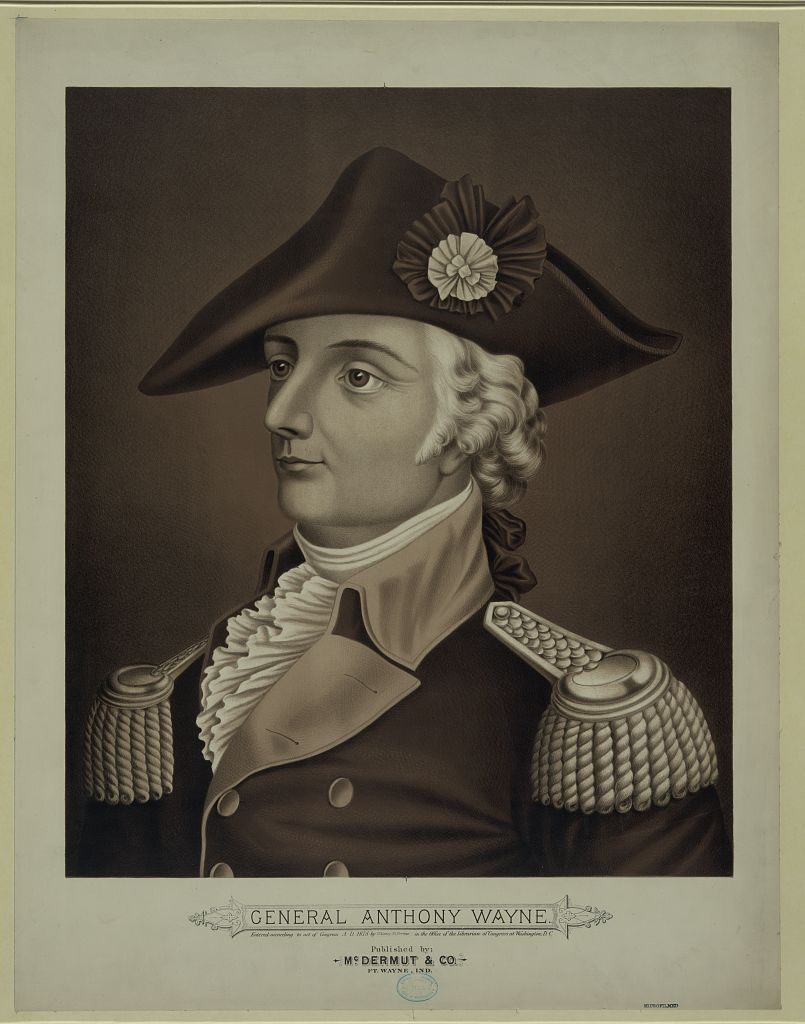

A print of General Anthony Wayne, 1878 (Photo: Library of Congress)

A print of General Anthony Wayne, 1878 (Photo: Library of Congress)

In the far west of the Philadelphia suburbs, just before the affluent Main Line area turns into horse-breeding farms, there is a grand mansion that sits with very little fanfare on a small street opposite a golf course. It’s called Waynesborough, and it’s the historic home of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne, the namesake of dozens of towns and townships and forts and other assorted places throughout the eastern United States. In this part of Pennsylvania, just a few minutes’ drive from Valley Forge, Anthony Wayne is a ghostly presence. Teenagers have awkward teenage dates at the Anthony Wayne theater, conveniently located in the town of Wayne. There are other towns called Waynesburg and Waynesboro. That golf course is part of the Waynesborough Country Club. Streets, schools, and businesses bear the name of Wayne.

And yet history teachers rarely give lessons about the life of “Mad” Anthony, a man whose military career spanned two wars, whom DC Comics decided was the ancestor of the fictional Bruce Wayne, and who is supposed to be haunting a highway that criss-crosses the entire state. Even weirder: Mad Anthony is buried in two places. Not two ceremonial graves: parts of him are literally buried in two totally separate graves, hundreds of miles apart.

Anthony Wayne was born to a wealthy family in what is now Paoli, Pennsylvania, my hometown, about 45 minutes west of Philadelphia by car. His family home is an enormous Georgian estate, all white pillars and stone, which remained in the Wayne family until a few decades ago. Anthony’s early life was varied; he was a surveyor in Canada, he worked at a tannery, he went to the college that would become the University of Pennsylvania (though he never graduated). But he found his calling at age 30 in the military, and quickly rose through the ranks.

A Keystone Marker for Wayne, Pennsylvania (Photo: Doug Kerr/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

A Keystone Marker for Wayne, Pennsylvania (Photo: Doug Kerr/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

“He was very militaristic,” said Bill Lange, park ranger and education coordinator at Valley Forge National Historical Park, the site of the famous revolutionary war battle where Wayne fought.

The myth of the Revolutionary War goes that the unorganized, untrained regional militias were responsible for upsetting the uptight, predictable, and preening British Army. But Wayne wasn’t a militiaman—in fact, he scorned them.

“Wayne was famous for his ferocious attacks, but he was very well read in military history and tactics, and really took being a soldier seriously,” said Thomas Fleming, author of How Mad Anthony Wayne Won The West.

Waynesborough home of General Anthony Wayne, near Paoli, PA (Photo: Smallbones/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Waynesborough home of General Anthony Wayne, near Paoli, PA (Photo: Smallbones/Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Wayne was, in fact, a professional, which was in rare supply in the fall of 1777, when the Continental Army seemed to be on its last legs. On September 20th, the Wayne-led troops in his hometown of Paoli were silently slaughtered with British bayonets in what’s alternately known as the Battle of Paoli or the Paoli Massacre. That winter, camping out in nearby Valley Forge, the troops were hungry and miserable, wondering what they were even doing there. Dozens deserted.

Enter Prussian-born American strategist Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, who preached fierce loyalty, lockstep training, and, well, a firm dress code. The soldiers at Valley Forge lacked the most basic of clothes, and it became Wayne’s job (among others) to find clothing. Eventually Wayne became obsessed with looking good on the battlefield, even earning yet another nickname, “Dandy Wayne.” He once wrote to George Washington: “I have an inseparable bias of an elegant uniform and soldierly appearance, so much so that I would rather risk my life and reputation at the head of the same men in an attack, clothed and appointed as I could wish, merely with bayonets and a single charge of ammunition, than to take them as they appear in common with sixty rounds of cartridges.”

Major General Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus, Baron von Steuben by Ralph Earl, c. 1786 (Photo: Public Domain/ WikiCommons)

Major General Friedrich Wilhelm Augustus, Baron von Steuben by Ralph Earl, c. 1786 (Photo: Public Domain/ WikiCommons)

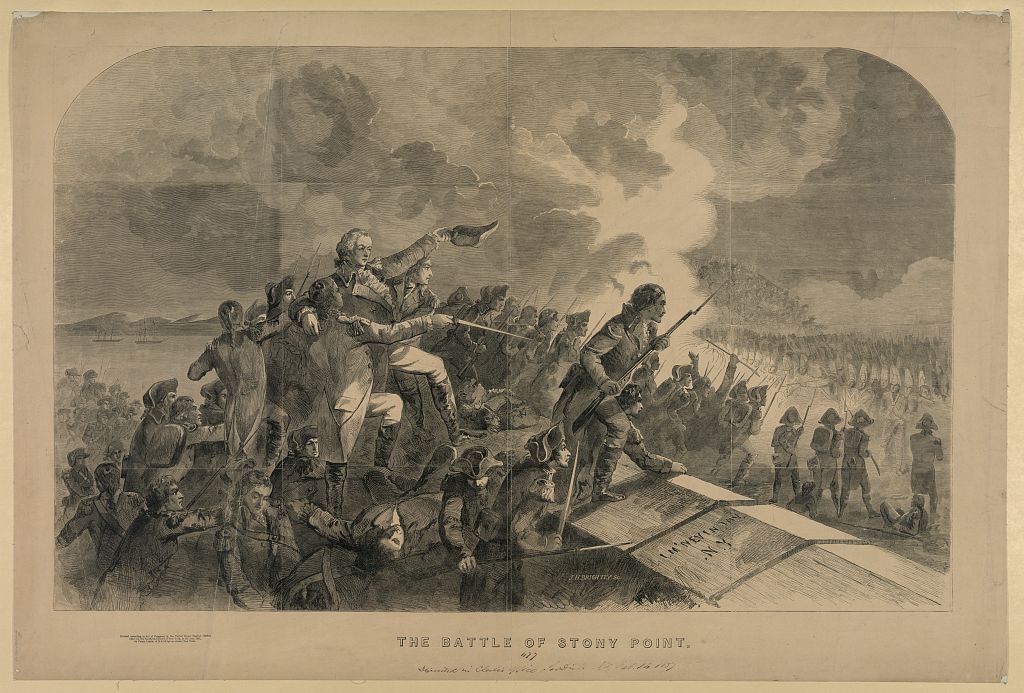

Von Steuben turned out to be right; after surviving the brutal winter of 1777-1778, armed with better training and a new set of duds, the Continental Soldiers were a whole new army. Wayne even led his division to a mirror-image defeat of the Paoli Massacre at the Battle of Stony Point, on the Hudson River north of New York City, using a silent bayonet charge in the night.

That kind of attack earned him the nickname “Mad Anthony” Wayne. Probably. In fact it’s not totally clear how he earned that name. Both Lange and Fleming told me he got the name from bold military moves and general bravery (he often served on the front lines of his own battles), but there are other theories relating to his legendary temper, cursing ability, and propensity to use violence on, or even kill his own men for stepping out of line.

A common theory holds that he was given the nickname by a sort of freelance spy and friend, who, upon behaving improperly at camp one night, was whipped thanks to orders from Wayne. The spy screamed that Wayne was “mad, mad.”

General Anthony Wayne and his men shown attacking a British fortification in ‘The Battle of Stony Point’ by J,H. Brightly (Photo: Library of Congress)

After the war, Wayne moved to Georgia, where he tried and failed for about 20 years to farm some land he was given. Luckily, there was a new war afoot, against various Indian tribes in what’s now Ohio, who had banded together to fight off the U.S. The tribes were a victim of some horrible chess playing; there was a clause in the Treaty of Paris that declared that all “indigenous lands” set up by the British would revert to American ownership at a certain time, so the Americans set out to reclaim what they saw as legally theirs.

The tribes found this ludicrous, that a treaty they had no part of could decide which of two foreign parties owned their ancestral land, and successfully repelled a few local American militias. George Washington, annoyed with the amateurish militias, brought his friend Mad Anthony up from Georgia.

Wayne landed in Pittsburgh and set about training the lousy group of soldiers he found there. “He had half of his army paint their faces all kinds of stripes and things like that, and then he sent them out into the forest,” said Fleming. “And then the other half attacked the first half, and the first half had orders to scream and yell and curse. They did this time and time again and soon enough they weren’t afraid.”

After priming his men for semi-racist Indian attacks, he went into Ohio and successfully slaughtered huge numbers of Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, near what’s now Toledo, thus ending that period of Indian rebellions. Here’s where things get weird. On his way home, Mad Anthony realized he was dying of gout, thanks to his lifetime diet of wine and rich foods. He made his way back to Pennsylvania as soon as he could, but died just outside of Erie, Pennsylvania, in the far northwest of the state, tucked up against the Great Lakes. He was buried there in December of 1796, but he did not stay there for long.

In 1808, only 12 years later, his relative decide they want his body to be buried at the family plot in Radnor, a few miles down the road from Paoli, but over 300 miles from Erie. So the same doctor who pronounced him dead was tasked with digging him up and transporting him. The doctor open his casket and found that the body was in surprisingly good shape, except for one leg, which had rotted. This was far from ideal: it was a long trip back to Radnor, and the recently exumed body would rot and stink most unpleasantly. The solution was gruesome.

The doctor carved up the body into smaller pieces and threw them in a pot of boiling water. The theory was, when you throw pieces of a chicken in water to make soup, the chicken meat falls off the bones and soon you have clean bones, which, says Lange, were really what Wayne’s family wanted to bury. This wasn’t that uncommon of a tactic; corpses were sometimes shipped from the U.S. to England, and the boiling technique was used to get clean bones then as well. Anyway, the doctor buried everything that came off the bones, including the knives used to scrape the bones clean and the pot used to boil them, back in the grave in Erie. The bones were sent southeast to Radnor.

But at some point in the journey, some of the bones were lost. “When the box arrives in Waynesborough, it’s not, um, complete,” said Lange. “There’s not a complete body there, some of it’s missing along the way.” Nobody knows whether those bones made it back into the Erie grave ,or whether they simply fell out of the coach on the way to Radnor, but legend sides with the latter. In fact, legend has it that every year, on Wayne’s birthday (New Year’s Day), Mad Anthony Wayne haunts the path his skeleton took on its way home, looking for his lost bones. That path is now U.S. Route 322.

That’s not the end of the ghostly elements of Anthony Wayne; Waynesborough itself is said to be quite haunted, both by Wayne himself and by the wife of his great-grandson, who died in a fire on the top floor in 1899. Allegedly women, and only women, have been able to hear ghostly screams, crying, and glass breaking.

Oh, and the Batman connection: In the DC Comics universe, Bruce Wayne, Batman himself, is a direct descendent of Mad Anthony Wayne. Bill Finger, one of the co-creators of the character, named Wayne not after John Wayne, as is commonly thought, but after Anthony. “Bruce Wayne’s first name came from Robert Bruce, the Scottish patriot,” wrote Finger. “Wayne, being a playboy, was a man of gentry. I searched for a name that would suggest colonialism. I tried Adams, Hancock … then I thought of Mad Anthony Wayne.”

General Anthony Wayne Monument in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania (Photo: slashvee/Flickr)

General Anthony Wayne Monument in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania (Photo: slashvee/Flickr)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook