The Hidden Gardens Producing Peaches Outside of Paris

They’ve survived for centuries.

(All photos by Anna Brones)

A version of this story was originally published in Makeshift magazine.

Before the era of urban sprawl, the outskirts of Paris were ripe with orchards. Hundreds of hectares produced kilos of fruits to feed the masses inside the French capital. Yet even as concrete and asphalt expand ever outward, plowing over centuries-old fields with new homes and roads, the spirit of homegrown farming is still embedded in the soil of the Parisian suburbs.

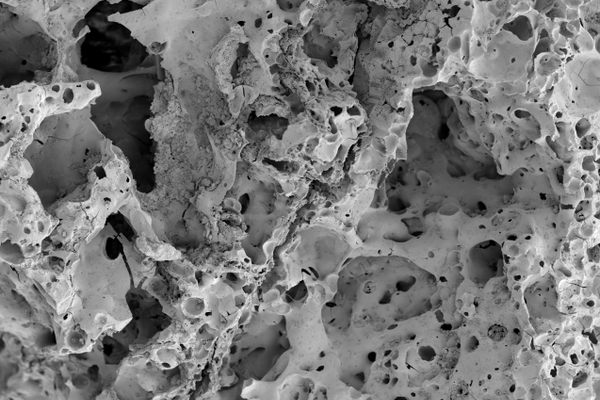

The suburb of Montreuil, just east of Paris, today houses some 100,000 people. But in the 18th to 20th centuries, it served as a hub of agricultural activity. At its high point, this area produced upwards of 15 million fruits a year, thanks largely to the murs à pêches, or ‘peach walls’. Established in the 17th century, this clever network — some 500 hectares of walls — helped protect the peach trees from the cold.

The north-south orientation of the walls and the ability of limestone to trap the sun’s heat provided a few extra degrees of warmth for the fruits, allowing them to flourish farther north than their usual habitat.

Amid urban sprawl and encroaching concrete, homegrown farming remains embedded in the Parisian soil.

The peaches of Montreuil became famous. They attracted royalty, earned a horticulturalist a prestigious Legion d’Honneur, and spurred an agricultural industry. Yet eventually, urban sprawl engulfed the walls.

“Today we are no longer in an [industrial] agricultural production,” says Pascal Mage, the president of the organization Murs à Pêches. He tends to the remaining 35 hectares of peach walls. Some are still home to peach trees, but others have been turned into gardens and are maintained by a variety of organizations devoted to the growth of urban agriculture. The result is a network of small gardens, all open to the public. “It’s a poetic place,” Pascal says.It’s Sunday, and despite the on-and-off downpour, members of the organization arrive to work on the orchards. One of the volunteers walks up with a peach in one hand and a knife in the other. She slices the fruit and passes pieces around.

Beyond the orchards that Murs à Pêches maintains, a maze of community gardens used for food production and education surround the plots made by the old peach walls. A medieval garden, called Jardin de la Lune, grows herbs and greens that would’ve appeared many centuries ago. Students from a nearby horticultural high school use the gardens for hands-on training — a reminder of more productive times, and an inspiration for the future.

As the world’s population continues to trend toward the urban, people move farther away from where food is grown. Paris, perhaps due to its history of mixing urban living with rural growing, seems to be ahead of the curve on this. Residents are keen to both draw on past experiences while innovating toward new ideas.

About a half-hour drive east of Montreuil’s farms, residents in the densely populated Ile-de-France region are pursuing gardens with a bit more buzz. Over 600 beehives dot the city — some even on the rooftop of the famous Opera Garnier — while vineyards hang in well-known neighborhoods such as Montmartre and Belleville, and near the Gare du Lyon train station in Bercy. Members of around 70 community gardens grow their own food, while rooftop gardens supply fashionable, top-tier restaurants. The city recently launched a gardening permit system for the outskirts of Paris, which allows people who want to keep the tradition of food production to select and maintain their own space.

Arable land is, of course, in limited supply in the city’s tightly packed suburban zone. This has forced harvest-minded Parisian entrepreneurs to find creative ways to keep feeding the local population, with the most viable option being atop the endless buildings.

Parisian suburbanites are reviving the region’s agricultural past with modern innovative twists.

Across the city, a flurry of rooftop gardening has taken hold in the last decade. Topage, a startup, is driving the movement. Its work includes Le Pullman Eiffel Tower restaurant garden, Yannick Alleno’s garden for the restaurant Terroir Parisien, and the research-focused 600-square-meter rooftop garden at AgroTech Paris. DIY and citizen-led projects have also garnered the attention of the city’s formal leadership. Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo has promised that within the next five years, 100 hectares of rooftops and walls will be turned into productive green zones.

Beyond maximizing space, rooftop agriculture offers other desirable gains. After decades of industrialization, the ground beneath Paris is saturated with heavy metals. The abundance of lead, cadmium, and zinc lodged in the earth is one of the reasons the Murs à Pêches doesn’t envision developing into a larger, full-scale agricultural production.

Production capacity of artisanal gardens remains small. Like at Murs à Pêches, many of the cooperative gardens in Paris usually produce just enough food to feed those who grow it. That’s far short of the 2 million people within the Paris city limits, or the more than 12 million people in the urban sprawl. While it’s hard to imagine that urban gardens could fully sustain the population, the region is slowly slimming down imported calories as independent producers continue to grow.

At the popular bar La Recyclerie, near Sacré-Cœur, visitors can find eggs from the chickens at their onsite urban farm. Veni Verdi, a five-year-old urban garden organization, sells the produce from one of its rooftop plots at a local cafe in Paris’ 20th arrondissement. The group’s latest initiative involves installing a rooftop garden on the ERDF (France’s electricity company) building, a stone’s throw from the area once known for its food markets, Les Halles.

Other groups are pushing to label locally grown food — a marketing ploy, perhaps, but also further incentive for Parisians to find new ways to produce homegrown eats. Doing so greatly ups the travel efficiency of the food consumed (and thus drops the ecological footprint). Local production also spurs community growth. “The residents invest in the space,” says Pascal, speaking of the Murs à Pêches members. This investment brings them food, but it’s also an accessible alternative to the rhythm of a modern metropolis.

Back in the Murs à Pêches, Pascal marvels at the tranquil, productive space within the city. “It’s the countryside,” he says, walking through the flourishing gardens and orchards, looking across the field. “It’s a change of scenery.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook