The Historical Reenactor Accuracy Wars

How to get ostracized at a Civil War reenactment: use bug repellant.

A re-enactment in action in Virginia. (Photo: Donnie Nunley/CC BY 2.0)

When you load up the car for a camping weekend set in the 1800s, the gear is a little different: Canvas tent. Wool bedroll. Hobnail boots instead of hiking sandals. Homemade food wrapped in wax paper. An ice cooler disguised as a wooden chest. Muslin underwear. Silk suspenders.

Anywhere you have dedicated history nerds who dream about the romance of the past, you’ll find reenactors reliving it, usually in the context of a dramatic struggle for the fate of a nation. In September 2015, a crowd of 75,000 gathered in a field south of Moscow to watch—or fight in—a pivotal 1380 battle between medieval Russians and Mongols. Three months earlier, 6,200 reenactors in Napoleonic garb recreated the 10-hour battle of Waterloo for the benefit of 64,000 spectators gathered in Belgium. For four years running, U.S. military history geeks have spent an April weekend sleeping in trenches at the Midway Village Museum in Illinois, facing mustard gas attacks from another continent a hundred years ago.

However, in the U.S., one period dominates the reenactment scene: the American Civil War. Sure, there’s a yearly “remember the Alamo” meetup in San Antonio, and New Englanders are happy to spend Patriots Day kicking off the Revolutionary war at Lexington and Concord, where the British are perpetually coming. But if you want to spend almost every weekend of the summer in one historical period, and practice your military drills year round, you join a Civil War unit. And as you load up your gear—your wool bedroll, your hobnail boots—you live in fear of one word: farb.

A Civil War re-enactment in Maryland. (Photo: Ron Cogswell/CC BY 2.0)

To call someone a farb is to call them inaccurate, with an added layer of moral judgment: a farb’s gear is not just wrong, but wrong, a sin against history. It’s reenactor slang that dates back to the 1960s, the dawn of the modern reenactment era, when the Civil War centennial and the civil rights movement coincided to cause a surge of mainstream interest in a hobby previously dominated by small-scale “town history” celebrations and marksmanship drills. In the same way contemporary comic con attendees snipe about “real” fans versus “fake geeks,” reenactors who devoted a lot of attention to the accuracy of their historical “impressions” complained about those who didn’t—and still do.

Your quintessential farb might spend all weekend talking on a cell phone, or wear a jumble of mismatched “old timey” costume pieces from different decades. Bright-colored crocheted snoods—decorative female hairnets—are a reliable target of ire; more 1940s than 1860s, they’re nevertheless sold to entry-level reenactors by opportunistic merchants happy to take money from a newcomer looking for a quick “period hairstyle” solution.

Farbs are an inevitable part of any large-scale reenactment, since perspectives on history—and what historical immersion means—are far from uniform. There’s natural tension between hobbyists who want to dress up and fire cannons, then sit down for a beer with fellow nerds, and people who want to get as close to time travel as possible—who would rather not see anyone duck behind a tree with a can of insect repellant.

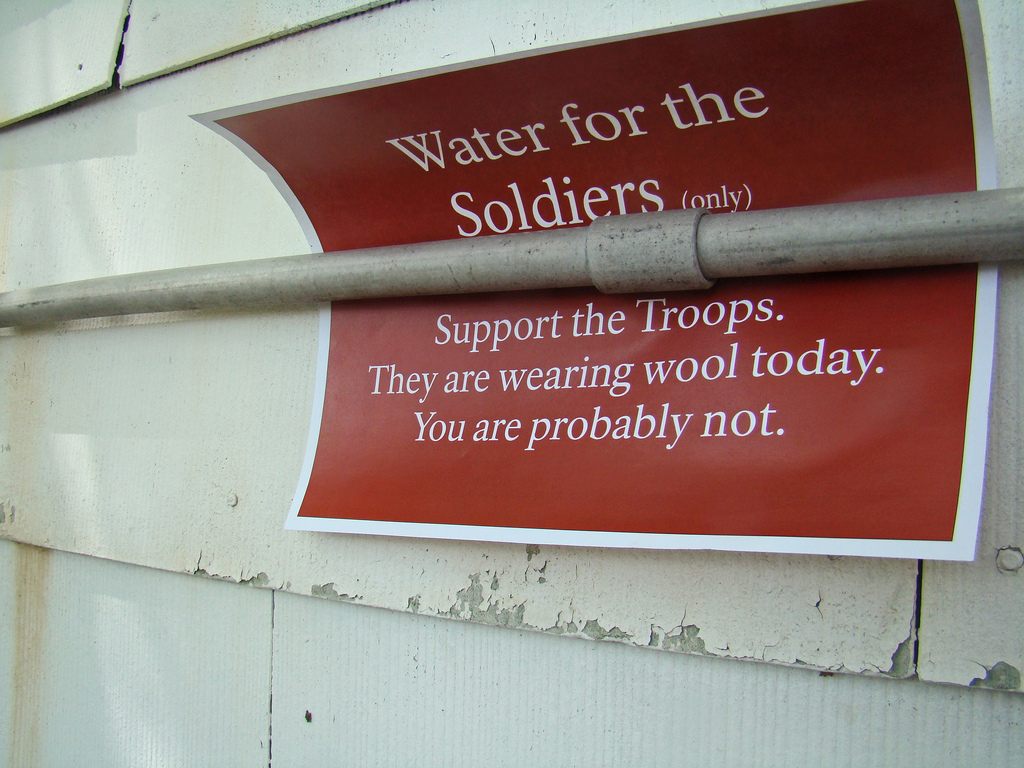

A sign at a re-enactment regarding historically-accurate costumes. (Photo: istolethetv/CC BY 2.0)

Emotional connection to the era adds another layer. As historian and Revolutionary War reenactor Seán O’Brien notes, a participant looking to honor his family’s memory of a much-mythologized ancestor “tends not to listen when you point out that wearing cavalry boots with breeches and a uniform coat six sizes too big with modern glasses and a bunch of medallions hanging off his hat doesn’t look anything like a mid-19th century uniform.”

Even for someone incredibly dedicated to historical accuracy, reenactment involves compromise simply by the fact of life in the present. Today’s corset-fancying woman would not have been shaped in one since the age of nine, and will therefore never achieve an 1800s-accurate ribcage shape. Nobody’s going to actually try to kill anyone, or forego prescription medication, or risk drinking unsterilized water during a battle. Wearing sunblock may be inaccurate, but so is a fresh sunburn because it’s been months since you spent a full day outdoors.

And since volunteers are paying for period-appropriate gear out of their own pockets, not everyone can afford to sink a few hundred dollars into 1862-accurate handmade shoes. Griping about someone else’s reenactment choices can quickly feel like sour grapes. No one is immune; a Confederate reenactor who was an extra in Glory bragged to filmmaker Gareth Harfoot that he’d pushed Matthew Broderick off a pier for not properly returning a salute—and gotten away with it by fading into the crowd with his impeccable costume.

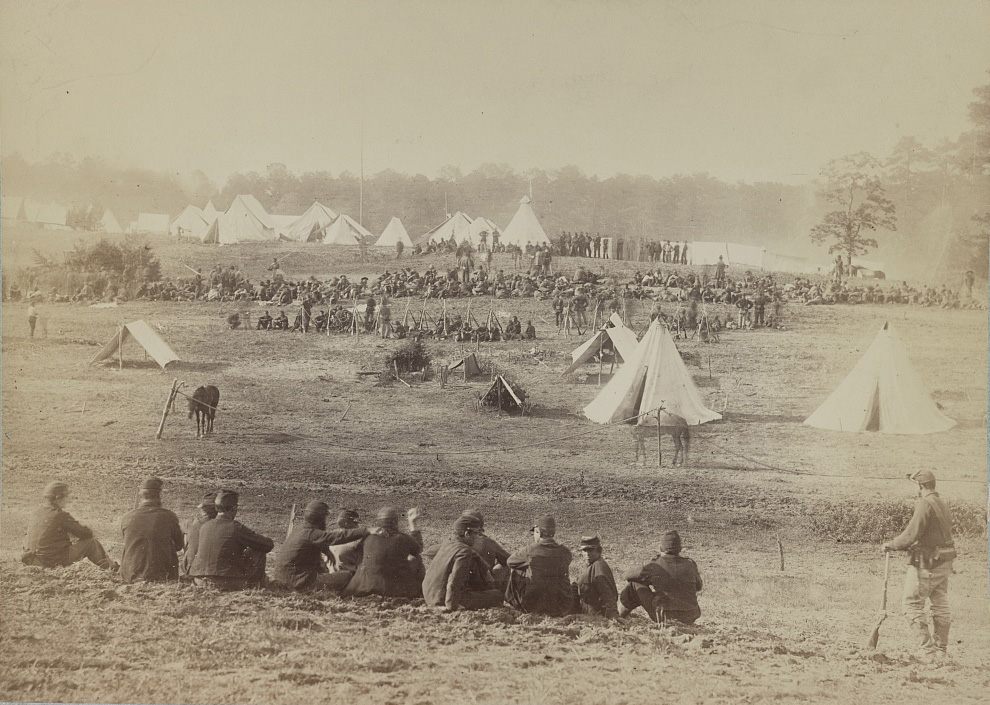

A photograph from 1864 showing Confederate prisoners captured at the battle of Fisher’s Hill, under the guard of Union troops. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ppmsca-15835)

However, the accuracy debate isn’t solely about reenactors. At large events, spectators outnumber reenactors by a factor of ten or more; these events are billed as educational “living history,” sponsored by museums and historical societies, and partly funded by spectators’ entry fees. Although onlookers will be able to spot prominent anachronisms like flashlights, they’ll take other historical compromises at face value.

When individual units and events set their own accuracy standards to determine who can participate, they enter a minefield of heated political arguments over who the hobby belongs to, and who it’s meant to serve. Should women be banned from fighting units? Aren’t reenactors overwhelmingly too old, too fat, and too white? At what point does a reenactment misinform more than it educates?

A cautionary tale is embedded in the term farb itself. Although it has several popular folk etymologies, it was most likely invented by the First Maryland “Blackhat” Regiment, led by German teacher Gerry Rolph. “Farb” is the German word for “color”—and during weekend sewing sessions in Spring 1961, the Blackhats mocked other units for too-colorful uniforms. Ironically, the original farbs may have been onto something: the Confederate army had a problem with blue, and therefore so do reenactors.

An illustration from 1895 showing the uniforms worn by Union and Confederate soldiers. (Photo: US Government/Public Domain)

Moreover, according to uniform historian Fred Adolphus, Confederate cadet grey may never have been as blue or as irregular as the shade reenactors have tried to recapture, based on a comparison of reproduction cloth with museum-conserved uniforms.

For symbolic reasons, the Confederate government wanted uniforms in the pale, bluish grey of state militias, to reinforce the idea that states had always been independent nations with a legal right to self-government. But the only fabric mills capable of producing that fabric in quantity were in the north, particularly around Lowell, Massachusetts. Thus Confederates spent the early years of the war in an array of mismatched hues as they tried different dye processes and imports. The homemade stuff tended to fade to brown after a few weeks or months in the sun—good camouflage, but demoralizing since “butternut” was an insult with the same meaning as “hayseed.”

Meanwhile, already-available manufactured fabric was often too dark a blue, to the extent that Union forces declared outright they’d execute as a spy any captured Confederate whose too-indigo uniform might be mistaken for a Federal soldier’s. Further complicating matters, Confederate uniforms sometimes were Federal uniforms with some of the color boiled out. Many of the deaths at the 1862 Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day of fighting in all of U.S. history, occurred because a Confederate unit under A.P. Hill was wearing captured Union uniforms, sowing confusion on both sides. (It’s equally but less lethally confusing for modern spectators.)

A print showing the Battle of Gettysburg. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-pga-03235)

Even once Southern industrial production of grey cloth had ramped up in places like Roswell, Georgia, and Richmond, Virginia’s Crenshaw woolen mills, achieving a regular, repeatable bluish gray was a challenge. The most readily available colorfast dyes of the time were indigo and black walnut, but “indigo’s tricky,” says natural dyer Jess Lionne, “because, first of all, indigo itself doesn’t dissolve in water.”

The same thing that stops indigo from washing out stops it from washing in, unless the dyer deoxygenates the water—usually by adding live bacteria and waiting a few days. This yogurt-like process smells like rotten fish, and attracts a lot of flies.

For a reenactor, the problem is obvious: no contemporary fabric company is going to use stinky, slow natural indigo instead of the synthetic version. However, the problem for uniform suppliers in the 1860s was indigo’s lack of predictability. Once dyeing begins, it’s hard to know in advance how dark a blue a vat will produce, since that depends on both bacterial activity and the potency of an individual indigo plant. To regularize the process, suppliers combed together dyed and undyed wool or cotton fibers until they achieved the desired shade with minimal heathering.

Costumed actors at a Civil War re-enactment. (Photo: Craig Shipp/CC BY-SA 2.0)

This process takes skill and machinery which are no longer readily available. Charlie Childs, founder of County Cloth, revered purveyor of Civil War reproduction fabric and clothing, relied on a 30-year partnership with Harry Lonsdale, a Philadelphia upholsterer who specialized in reproduction wool for refurbishing classic cars. Since Lonsdale’s recent retirement, Childs has been on an unsatisfying quest to find a worthy replacement. A long process of sending swatches back and forth between Childs (himself an experienced handweaver), a mill, a dyer, and a spinner, may still result in cloth that isn’t quite right.

As Mark Twain wrote in The Gilded Age, his co-authored 1873 satire of post-Civil-War corruption, “History never repeats itself, but the Kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends.”

It’s not quite the same as saying history rhymes; but it’s a little like saying there will be reenactments, and they’ll get a bit farby. Or that 150 years after a war about skin color and about fabric, men will still fight a battle of blue versus grey.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook