The Last Place to Experience 2016 Will Be an Abandoned Island Full of Bird Poop

Baker Island, in the middle of the Pacific, is one of two islands in the world in time zone UTC-12:00.

As 2016 draws to a close, just about everyone is thinking the same thing—boy, are we going to miss it! Every year must end, but something about this one was special: maybe the unceasing political turmoil, or the spate of celebrity deaths, or all those charming, friendly clowns.

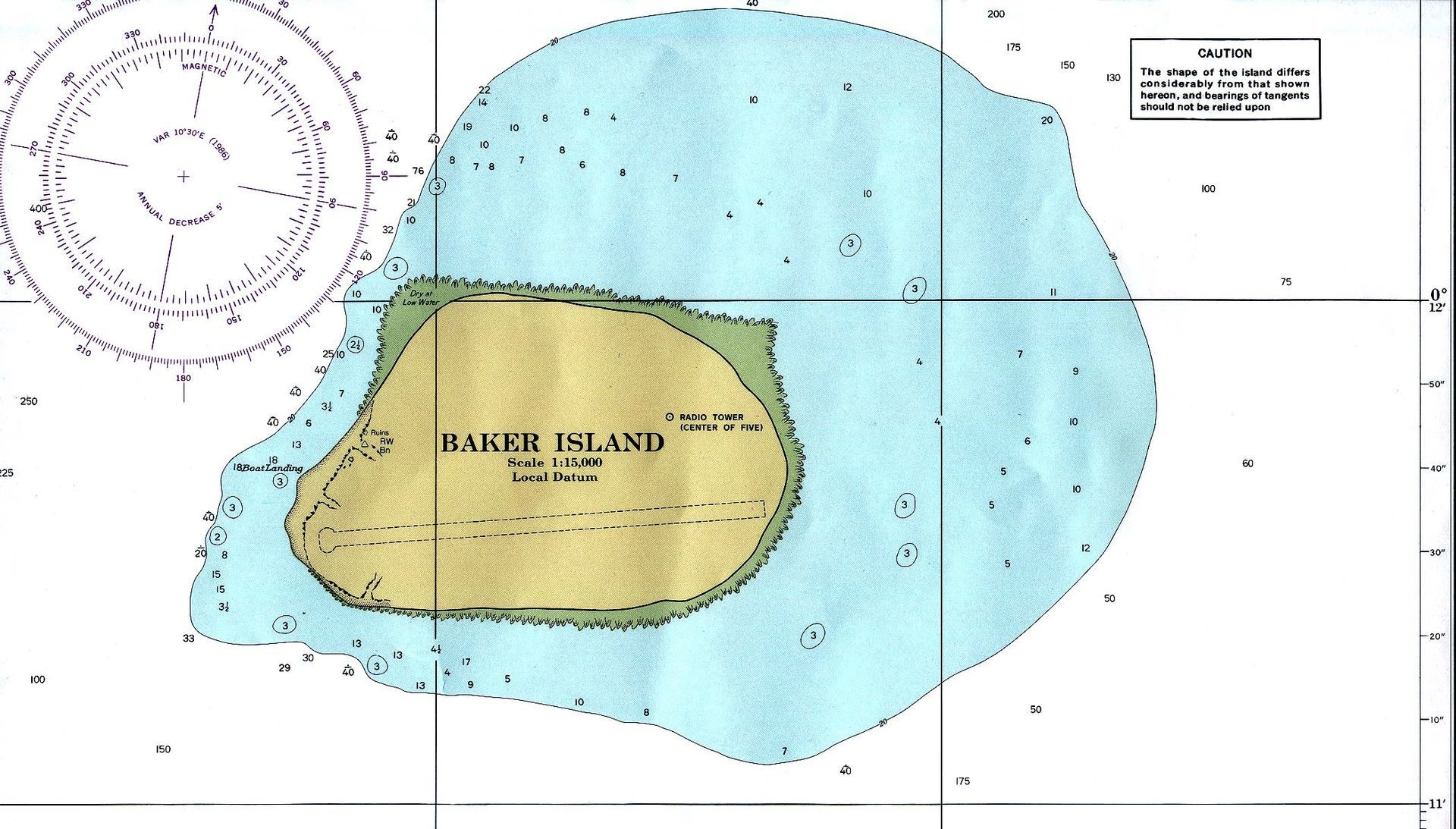

Nothing gold can stay. But if you want to squeeze just a little more out of 2016, we’ve got just the place for you to do it: Baker Island, a tiny, saucer-shaped atoll in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. Located halfway between Hawaii and Australia, Baker Island is one of only two named pieces of land in the world to fall within the time zone UTC-12:00. (The other is its neighbor, Howland Island.) This makes it the last place on Earth where each day—and thus each year—finally ends. Below is a brief guide to this prime New Year’s Eve location, where, surrounded by bird poop and boobies, 2016 will breathe its dying breath.

What is Baker Island?

Baker Island is an atoll—an island made out of a jutting coral reef—about 1,500 miles southwest of Hawaii. It is not quite a mile square, and is, for the moment, completely uninhabited (by people, at least). Although it was certainly frequented by Polynesian sailors, its first “official” sighting was in 1818, by the occupants of the whaling ship Equator, and for a few decades after that it served mainly as a place to bury dead seamen. In 1855, it was sold to the American Guano Company, who set up camp there to harvest the plentiful mounds of bird poop, which one expert called the “finest he had seen.”

Attempts to make the island anything more than a giant bird poop repository—a would-be settlement in 1935, a military air base project in 1943—have mostly been stymied by the enormous number of birds that already live there. In 1974, the US gave up and declared Baker Island a National Wildlife Refuge, part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

How can I get there?

Like most worthwhile New Year’s Eve spots, if you want to visit Baker Island, you’ll have to make your plans far in advance. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sends a boat over once every two years or so to make sure everything is still going well. In order to be on it, you need a special permit that is generally only afforded to researchers and educators. If you get past these bureaucratic bouncers, you’re facing eight days at sea, after which you’ll arrive at a small landing on the island’s west coast.

What should I wear?

Baker Island is located just north of the equator. According to the CIA World Factbook, it enjoys “scant rainfall, constant wind, [and] burning sun”—so dress accordingly! For this special occasion, you may want to coordinate your outfit with the island’s vegetation, which consists mostly of grasses, short shrubs, and vines that grow on the ground.

Who will I meet there?

Currently, most of the residents of Baker Island are seabirds—largely boobies, frigatebirds, and sooty terns. Two types of reptiles, the snake-eyed skink and the hawksbill turtle, also hang out there, along with hermit crabs and various insects. A contingent of 40 bottle-nosed dolphins generally greets boats on arrival. There are also a heck of a lot of Norway rats, which eat bird eggs.

What attractions should I be sure not to miss?

At a slim 0.8 square miles, you’d think there wouldn’t be a lot of Baker Island to love—but what there is of the island packs a wallop. You can squelch around remnants of the guano trade—one 2006 travelogue describes a scraped-out basin beside several remaining “piles of low-grade guano.” Once that gets old, there’s an overgrown former airstrip, a decrepit radio tower, a lone cistern, and a crumbling day beacon that fills with shade-seeking hermit crabs during the hot days. The most stunning attraction, however, can’t be visited at all—like most atolls, Baker Island lies atop an enormous underwater volcano, which dates back to the Cretaceous era. Just because it hasn’t blown in a while doesn’t mean it won’t on New Year’s Eve—think of the fireworks!

If Baker Island is too crowded, where should I go instead?

There is one other named piece of land that falls within the UTC-12:00 zone—Howland Island, which is much the same as Baker, with the added distinction of having been the intended destination of Amelia Earhart when she disappeared in 1937. Let’s hope the same fate does not befall 2016—which, for all its faults, is at least guaranteed a final landing on these islands before it finally relegates itself to the guano heap of history.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook