The Lost and Found Art of Assembling Whale Skeletons

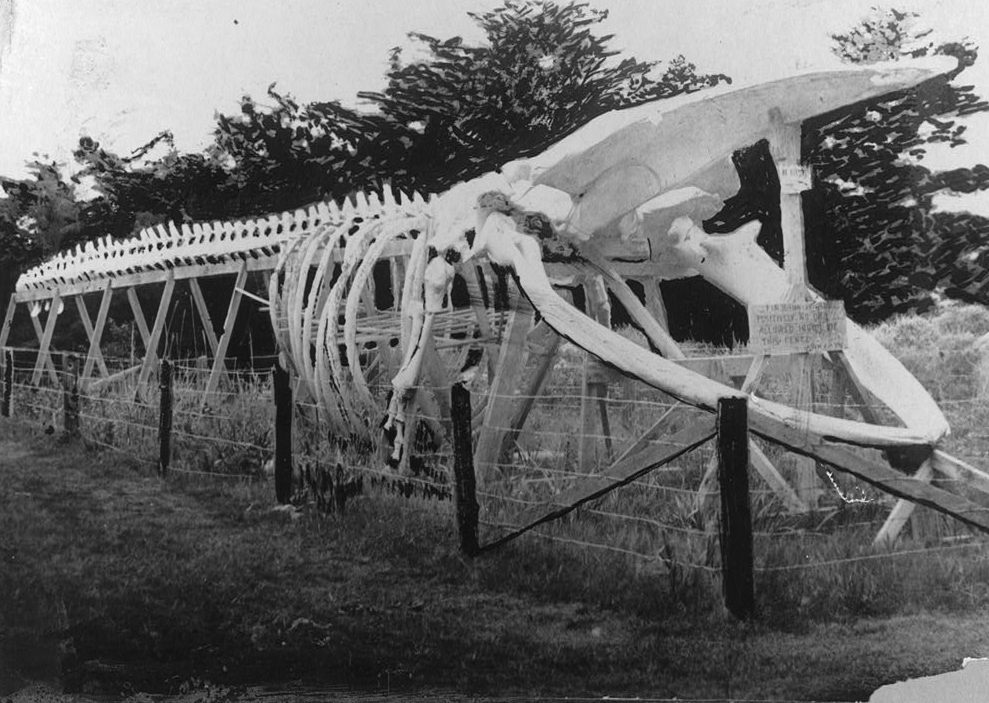

Skeleton of a whale in Alaska, 1900. (Photo: Library of Congress)

In the late 1970s, a 17-foot beaked whale washed up on the shore of a small community called Homer, Alaska. The town’s natural history center, the Pratt Museum, de-fleshed and cleaned the skeleton, but what do you do with hundreds of large, loose bones?

The skeleton had seen better days. The bones were darkened or split, still heavy with pungent whale oils, and stacked in dark museum storage. Two years after the discovery, the museum wanted to make a whale articulation–the lifelike assembly of a skeleton–but lacked the resources to find out how.

Lee Post, a former bicycle mechanic who co-ran a bookstore, had loved animal bones and natural ephemera since childhood. He volunteered at the museum working with smaller skeletons; when he heard about the mysterious whale bone challenge, he jumped at the opportunity. Post set to work, searching for the instructions to help him begin his dream project: assembling a large skeleton for a natural history museum.

Lee Post working on a recent whale articulation. (Photo: Lee Post)

But the investigation was a flop. Post tried to order a book on the subject, but there were none to be found. He made hopeful calls to museums where he’d seen whale articulations before, and prepared to ask the experts themselves, but to no avail.

Post still recalls this in disbelief: “It turned out all the whale skeletons I remembered were done more than 100 years before that, by people long dead, who left no instructions on how they did them.” The skeletons Post knew of were a legacy that reached back into time, and he saw them during a unique lull in the history of whale bone enthusiasts.

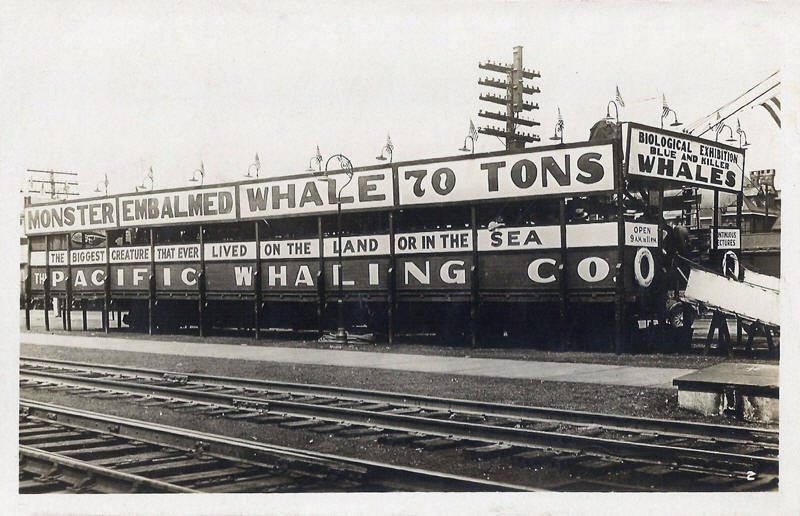

Humans have been fascinated with cetaceans–the taxonomic order that includes whales and dolphins–for over 2,000 years. In the first century BC, Palestinians wheeled a whale skeleton hundreds of miles to awe Roman crowds. Europeans in the 1600s illustrated beached whales as monsters and bad omens, surrounded by bewildered audiences. And in the 1860s, a whale from Gothenburg, Sweden was shuffled across European cities and set up as a morbid cafe, recounts Joe Roman in his book, Whale. A passerby would see large whale jaws hinged toward the sky, revealing upper-class social adventurers drinking tea in its cavernous throat.

An engraving of a beached whale with allegorical references to natural disaster, death, and the plague by Jan Saenredam, 1602. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

By the late 1800s, museum exhibits had evolved from their origins as personal status-boosting collections, and the British Museum and American Natural History Museum became established institutions. While many curators couldn’t get their white-gloved hands on a coveted dinosaur skeleton, practically anyone could get access to a commercially hunted whale.

Whale displays reigned supreme for over 100 years: “Jonah”, the humpback whale, rotted across the U.K in the 1950s as an unpreserved exhibit and memorable olfactory experience. In 1967, traveling showman Jerry Malone bought one of the last whale carcasses hunted in the United States, froze it with liquid nitrogen, and carted it around the country as “Little Irvy” until 1995.

“Virtually every museum had a whale. But over the years they became decrepit, dinosaur-looking, dark with oil in them, no exciting poses,” says Post. “Over the decades they got taken apart and then there were not a lot of places that had them.”

Monster Embalmed Whale show of the Pacific Whaling Company, date unknown. (Photo: Courtesy of Sideshowworld.com)

To make matters for future bone enthusiasts more difficult, museums rarely had whale skeleton experts on staff. They outsourced their stock to design firms–a practice that many museums continue today. Henry A. Ward, an adventurer and naturalist, sent so many specimens to museums in the late 1800s that it became his primary trade. Sadly, many whale experts died in the early years of the 20th century without recording their knowledge, forever guarding proprietary secrets.

Post managed to find “three to four” people in North America who made attempts at whale articulation first-hand, but learned that no one was doing it exactly the same way. In fact, many were copying the outdated anatomy of skeletons from the previous century, or using techniques to connect and preserve bones that seemed rickety and short-lived. Large marine animal bones present unique challenges; size, weight and natural oil content. To do this right, the process had to be reinvented.

Completed beaked whale articulation by Lee Post, hung at the Pratt Museum. (Photo: Lee Post)

Post consulted people who had articulated moose or elephants, and even “anyone interesting” who walked into his bookstore–artists, mechanics, and carpenters–until trial and error revealed solutions that worked. During the dark Alaskan winter he worked intently on his own, and slowly assembled the skeleton in a small museum workspace. Ultimately, Post wrote and illustrated the world’s only whale articulation manuals, and fueled the first resurrection of whale articulation experts since the early 20th century.

More people began to study the craft; over 15 whale articulations now exist in the U.S. with more projects in the making. These days, Post and his colleagues rarely go at it alone. “I admire anyone who’s put together a large whale, because it takes so much time and commitment right from the beginning” says Keith Rittmaster, a biologist and natural science curator at the North Carolina Maritime Museum who is is one of the top whale articulation specialists in the country. In 2012, he and volunteers completed the ambitious “Bonehenge” project: an eight-year-long effort to articulate a 33.5-foot sperm whale.

Sperm whale, shortly after it was found on the beach. (Photo: Keith Rittmaster and the Cape Lookout Studies Program)

When a whale washes up on the beach, it’s usually deceased–sometimes rotten or half-eaten. Rittmaster’s sperm whale was somewhat of an anomaly: it lived long enough to arrive ashore, and then abruptly passed away. “The body was still warm! That’s when the excitement came in. This is an endangered species, it’s super fresh, and we have veterinarians who can do a knock-out necropsy,” says Rittmaster, whose evident enthusiasm for his work is contagious.

Necropsies, autopsies performed on non-humans, are vital to marine center research. He and a team spent weeks cutting off flesh, dismantling ribs, preserving the heart, and even x-raying the whale’s pectoral fin for later reference.

How the whale is prepared depends on the size, location, and freshness of the remains, but many methods are similar. After the body is secured, its parts are examined and processed. Teeth may be sliced to estimate the whale’s age, their inner layers counted like tree rings. In some cases the bones are composted or buried for years, in others they are stored in underwater pots until ocean creatures eat residual flesh. Large bones–like the skull of Rittmaster’s sperm whale–are tidied by bacteria through a maceration process, which includes a nine-month stay in a water and horse manure pond.

Burying the sperm whale after the necropsy. (Photo: Keith Rittmaster and the Cape Lookout Studies Program)

When the bones are de-fleshed, they can be treated with a trichloroethylene vapor degreaser, an industrial solvent that reduces bone weight, stench, and bacteria. Another soak in hydrogen peroxide evens color and further cleans the bones. No trade tool is left untouched–bookbinder’s glue can be applied to preserve color before bones are placed into jigs, drilled for metal supports, and held together with expert welding and fitting tactics.

The extensive time and care put into whale articulation today creates humbling and impressive exhibits. In contrast to opportunistic shows of the past however, recent articulations are mainly meant to educate. When Rittmaster thinks of why it’s important to do this at all, it’s because of the fragility of marine life. “The number of different species is shocking–even to me, who’s been studying these things for 30 years,” he says.

“When oil companies are applying to our federal government to use seismic noise in order to drill for oil, I want people to know what we stand to lose.”

Sperm whale atlas bone, after being buried for three years. (Photo: Keith Rittmaster and the Cape Lookout Studies Program)

This is a fairly new line of thinking. For most of history, whales were seen as otherworldly creatures or, less poetically, commercial opportunities–heating oil and transmission fluid among them. As the public became familiar with the gentle, intelligent whale narrative for the first time, as in Jacques Cousteau’s 1955 underwater film The Silent World, the idea of using whale bodies for profit was increasingly seen as inhumane. Conservationists today study whale organs and bones for proof of how humans affect ocean life. It’s a sort of forensic investigation that induces laws, like speed limits for vessels that strike whales, toward protecting endangered species. In just a few decades, whales came to represent everything we need to protect instead of the alien unknown.

Post believes that whale bones will never fail to provoke awe. “No matter what happens in the museum world…there will be people who are fascinated by skeletons, by bones,“ he says. “That’s happened since cavemen days–I think there were troglodytes in caves that people were picking up and thinking ‘this is cool.’”

One wonders where this is all going. Will we hit another whale articulation peak? Will the experts of today fade over time, only a few dusty articulation manuals left in the world? “Maybe there will be 3-D printed bones, or skeletons with motors in them,” says Post. But the real thing always seems more interesting. Bones have entranced people all over the world for thousands of years, in particular the knowledge that they once functioned in live creatures, in a way not so differently from our own.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook