Hidden 25 Years Behind an Apartment Wall, A Spectacular Synagogue Mural Is Rediscovered

Tucked away in an apartment building in the city of Burlington, Vermont is an extraordinary wall painting known as the Lost Shul Mural. The mural, which adorns the apse of a former synagogue–“shul” means synagogue–was hidden behind a wall for 25 years. It is the only known remaining example of pre-Holocaust Jewish synagogue folk art in the United States, and one of the best-preserved surviving examples in the world.

The Lost Shul Mural today (Photo by Amanda Levinson).

The Lost Shul Mural today (Photo by Amanda Levinson).

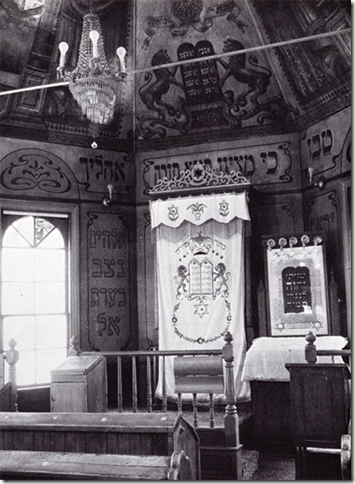

The story of the mural begins in 1889, when a group of Jewish Lithuanian immigrants built a wooden synagogue in Burlington they called Chai Adam. In 1910, the congregation hired a Lithuanian Jewish artist named Ben Zion Black to paint a mural in the style of religious Jewish art then popular in sanctuaries across Eastern Europe. The mural depicts the curtains of a tent, pulled back to reveal bright rays of divine sunlight shining down on an ornate crown - the scroll beneath it reveals it is the “crown of the Torah.” The crown hovers above the tablets bearing the Ten Commandments. These tablets, in turn, are flanked by two lions, symbols of the Jewish people. For the original congregants of Chai Adam, the mural provided not only spiritual comfort; It was also an important cultural link between the old world of Lithuania and their adopted homeland.

It was the only religious mural that Black, who was also a mandolin player, actor, Yiddish poet and playwright, would paint. A secular Jew, he went on to own a commercial sign company, “Signs of the Better Kind,” for 50 years, and wrote poetry for Yiddish newspapers.

The Chai Adam Synagogue in 1910 (Photo from Lost Shul Mural Committee).

In 1939, Chai Adam merged with another congregation and closed its doors. The building was sold several times and was used at one time as a warehouse, exposing the mural to dust and smoke. In 1986, the building was converted into apartments. Members of Burlington’s small Jewish community had the foresight to hide the mural behind a false wall, in the hopes it could be recovered and relocated at some future date.

In 2012, a small band of community volunteers, led by Aaron Goldberg, a local lawyer and descendent of Burlington’s earliest Jewish Lithuanian families, opened the false wall to check on the mural’s condition. The further deterioration of the mural persuaded the group that the time had come to embark on the costly and laborious process of working with architects, conservators and museum experts to safely relocate the mural. Following an ambitious fundraising campaign has raised $325,000 to prepare and stabilize the mural, it is ready to be moved to a local synagogue, where it will be completely restored and puton view to the general public beginning in May 2015. The relocation and restoration are expected to cost an additional $300,000.

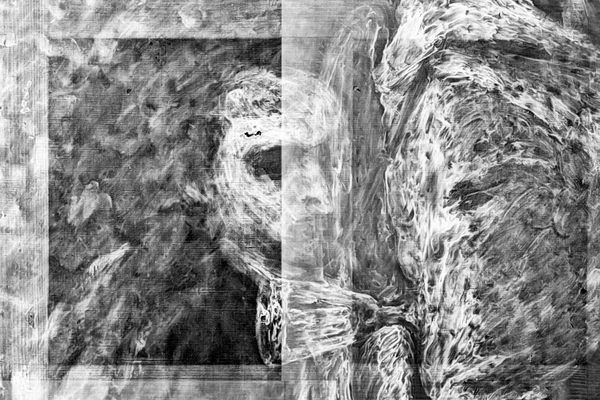

Close up of the mural’s lions (Photo by Amanda Levinson).

Close up of the mural’s lions (Photo by Amanda Levinson).

Jews started as a nomadic people and aren’t always thought of as one the world’s great material cultures. The “Lost Shul Mural”– its name now freighted with the melancholy of post-Holocaust diaspora–invites us to learn about cultural survival not only through the stories we hear from families, the ever-growing bookshelf of Holocaust histories, or through religious observance (which is declining in the United States), but also through the architecture and objects that embody Jewish history and Jewish values.

Says Dr. Samuel Gruber, President of the International Survey of Jewish Monuments, “The Burlington mural is a treasure. It is vivid and evocative. The colorful mural is by itself a unique work of synagogue art, but it also embodies a larger and mostly lost Jewish tradition of religious decorative painting.” For contemporary viewers, the Chai Adam mural is a vibrant and rare example of a once-prevalent folk art tradition that was destroyed, along with thousands of synagogues and millions of lives, during the Holocaust. It is also a potent symbol of the endurance of a people.

Lost Shul Mural (Photo by Amanda Levinson).

Lost Shul Mural (Photo by Amanda Levinson).

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook