The Lust Branch: “Private Matters” of Eccentric Musician Percy Grainger

Australian composer Percy Grainger. All photographs courtesy of the Grainger Museum unless otherwise stated.

Australian composer Percy Grainger. All photographs courtesy of the Grainger Museum unless otherwise stated.

Not for nothing is Percy Grainger (1882-1961) considered Australia’s most eccentric composer. In 1956, visiting his homeland from the United States, he deposited a mysterious locked chest marked “Private Matters” in his Melbourne bank vault, with instructions not to open it until 10 years after his death. Imagine the shock and scandal when the researchers and archivists who did the honors in 1971 discovered a Pandora’s Box containing more than 70 homemade whips (some fashioned out of conductors’ batons), an extensive pornography collection, and candid photographs documenting Grainger’s fetish and bondage experiments in clinical detail. He stipulated that these intimate artifacts be displayed in what he conceived of as the “Lust Branch” of the unassuming red-brick Grainger Museum he himself had founded (and funded) at the University of Melbourne; a rare example of an autobiographical museum endowed by its subject.

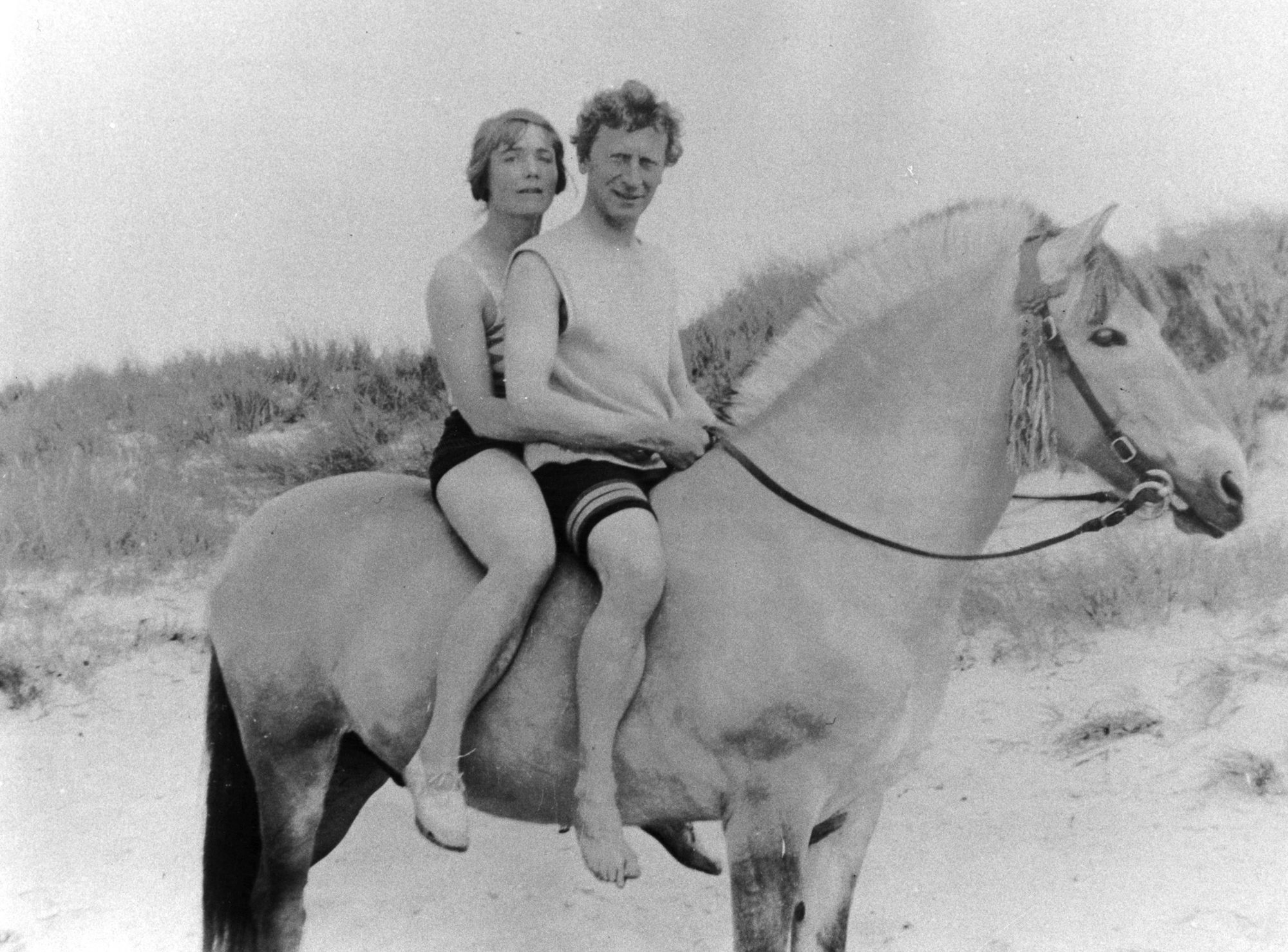

Percy Grainger on horseback (Photo courtesy of the Grainger Museum)

Percy Grainger on horseback (Photo courtesy of the Grainger Museum)

So why air all that dirty laundry in public (there are, in fact, blood-stained shirts in the collection)? Grainger had begun experimenting with sadomasochistic practices by the age of 16. In 1928, in a letter to his future wife Ella, he confessed his “hot wish”: “As far as my taste goes, blows [with the whip] are most thrilling on breasts, bottom, inner thighs, sexparts.” In his manifesto Aims of the Museum, written in 1955, he states that the “contents of the Grainger Museum have been assembled with the main intention of throwing light upon the processes of musical composition.” And since he believed that his sexual proclivities and creative drive were inextricably linked, he decided that the public would need an all-access, backstage pass in order to truly understand his art.

Just as well he wasn’t shy – his bid to display his own skeleton in the museum after his death was rejected on the grounds of public indecency. But just about everything else you could imagine is there – and quite a few things you might struggle to imagine. Percy Aldridge Grainger: sounds like a minor Harry Potter character, and perhaps that’s not too far off considering the Australian piano virtuoso, conductor and composer often dressed like a wizard in his self-designed terry-towelling harlequinerie (some of which can be found in the museum), and was known to wave a wand in front of orchestras of some repute. Makes you wonder how Dumbledore expressed his dark side behind closed doors.

Just as well he wasn’t shy – his bid to display his own skeleton in the museum after his death was rejected on the grounds of public indecency. But just about everything else you could imagine is there – and quite a few things you might struggle to imagine. Percy Aldridge Grainger: sounds like a minor Harry Potter character, and perhaps that’s not too far off considering the Australian piano virtuoso, conductor and composer often dressed like a wizard in his self-designed terry-towelling harlequinerie (some of which can be found in the museum), and was known to wave a wand in front of orchestras of some repute. Makes you wonder how Dumbledore expressed his dark side behind closed doors.

The museum was inaugurated in 1938 (and reopened in 2010 following three years of extensive restoration). Over the decades, Grainger obsessively collected and shipped off more than 40,000 items of correspondence, along with photographs, music manuscripts, furniture, and personal effects – right down to his dentures. What emerges is a detailed portrait of a complex man, one of Australia’s true iconoclasts.

Above is a selection of whips from the Lush Branch of the Grainger Museum. (Photo courtesy of www.bentleather.com)

Grainger modelling brightly-colored terry-towel clothes of his own design. (Photo courtesy of the Grainger Museum)

Grainger modelling brightly-colored terry-towel clothes of his own design. (Photo courtesy of the Grainger Museum)

Although his popular arrangement of the English folk ditty Country Gardens is one of his only works to remain in the public consciousness today, he was a major personality of the early 20th century, a friend to composers George Gershwin, Duke Ellington, Edvard Grieg, and Frederick Delius; his wedding was held at the Hollywood Bowl before a paying audience of 20,000. Beyond his celebrity as a concert pianist, he was an avant-garde thinker, experimenting with electronic music as early as 1937. He composed for the solovox and theremin as well as inventing his own instruments; those on display at the museum include the “Butterfly Piano” tuned in 1/6 tones, and a “Kangaroo Pouch” oscillator designed to sound like a malfunctioning air-raid siren.

“Butterfly Piano,” Grainger’s own design. (Photo courtesy of the Grainger Museum)

“Butterfly Piano,” Grainger’s own design. (Photo courtesy of the Grainger Museum)

Just as intimate as the “Lust Branch” in its own way is the section dedicated to Grainger’s syphilitic mother Rose, with whom he had an abnormally close relationship up until her suicide in 1922 amid rumors of incest. Percy added to the collection her final note (signed “your poor, insane mother”), the contents of the handbag she had been carrying the day she jumped from the 18th floor of the Aeolian building in New York, and – perhaps the most eerie item – a lock of her hair.

The contents of Rose Grainger’s handbag on the day of her suicide in 1922. (Photo courtesy of the Grainger Museum)

The contents of Rose Grainger’s handbag on the day of her suicide in 1922. (Photo courtesy of the Grainger Museum)

Rose’s death contributed enormously to her son’s desire to preserve every last trace of his own life – and not just through his musical legacy. “I am hungry for fame-after-death,” he told his wife. And even if his work is rarely heard in concert halls today, the astounding breadth and eclecticism of material he deposited in his personal “hoard house” ensures that it’s not just musicologists – or S&M enthusiasts – who pay him a visit. If music be the food of lust, play on.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook