The Only LGBT Cemetery Section in the World Was Inspired by J. Edgar Hoover

A section of D.C.’s Congressional Cemetery has become a gathering place for honoring LGBT activists.

Leonard Matlovich’s grave at Congressional Cemetery. (All photos courtesy of Paul Williams)

Congressional Cemetery, just east of Capitol Hill in Washington, has been dubbed “America’s hippest cemetery.” It entices the living to its grounds with offerings of yoga sessions in the chapel, al fresco movie nights, and dog-walking groups. The cemetery also has a feature that, according to the administration, is unique among cemeteries around the world: a “Gay Corner.”

Congressional’s LGBT section, in the cemetery’s northwest, began with a man named Leonard Matlovich. In 1975, Matlovich, a Vietnam vet, had been in the Air Force for 12 years and had an unblemished service record. On March 8 of that year, he sent a letter to his superior officer confirming that he was, indeed, homosexual.

Military regulations at the time clearly stated that “homosexuality is not tolerated in the Air Force.” At a hearing into the matter, government counsel asked a psychiatrist named Dr. Money “whether Sergeant Matlovich’s continued presence in the military might pervert sexually normal servicemen.” Dr. Money said no. Matlovich was discharged anyway.

Following his dismissal from the military, Matlovich became a committed activist. “He had a lifelong fight for LGBT inclusion in the military, way before ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’” says Paul Williams, president of Congressional Cemetery. One of the great legacies of this fight, and the foundation of the Gay Corner, is Matlovich’s tombstone.

Leonard Matlovich’s funeral in June 1988.

In 1984, Matlovich purchased two adjacent plots at Congressional—one for himself, and one for a future partner. He chose the location of these plots because of their proximity to two notable graves: those of J. Edgar Hoover, and Clyde Tolson. Hoover, the first and longtime director of the FBI, waged an anti-gay war during the 1950s and ’60s, spying on suspected gay employees of the government and referring to them as “sexual deviates.” Tolson was Hoover’s longtime colleague, friend, and, according to many, romantic partner.

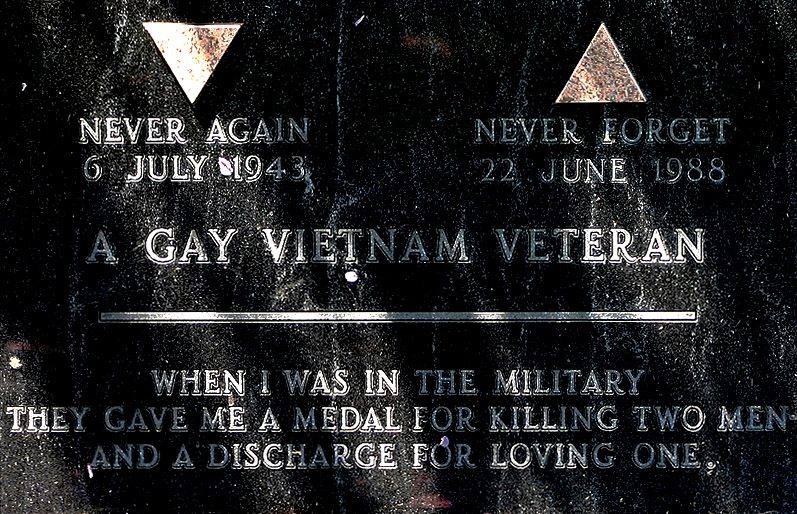

Matlovich designed his own headstone with great care, intending it to serve as a memorial for LBGT veterans. He chose reflective black granite so the stone would resemble the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall. He placed pink triangles on it and, instead of emblazoning it with his own name, used the more inclusive phrase “A Gay Vietnam Veteran.” Most striking of all was the epitaph: “When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one.”

The inscription on Matlovich’s tombstone.

In 1988, four years after buying his plot, Matlovich died at 44 of complications from AIDS. His self-designed memorial, and the poignant message inscribed on it, inspired other LGBT veterans and activists to purchase their own plots near Matlovich’s grave. Some of these people were HIV-positive. During the earlier years of the AIDS epidemic, says Williams, “a lot of other cemeteries wouldn’t bury [people who had contracted HIV] because they were scared of the disease. Our cemetery has always been inter-denominational and inclusive, so we didn’t have a problem with that.”

Williams says that about 35 people have chosen to be buried in the LGBT corner to show solidarity with Matlovich. The footstone that reads “Gay is good” memorializes Frank Kameny, who in 1957 was dismissed from his position as an astronomer in the U.S. Army Map Service because of his homosexuality. In the ’60s, Kameny was president of the D.C. chapter of the Mattachine Society, which sent pro-gay literature and campaign letters to high-ranking politicians—all the way up to President Lyndon B. Johnson. The society also made sure to include J. Edgar Hoover on its mailing list, much to his ire.

Frank Kameny’s grave. Kameny coined the phrase “gay is good” in 1966.

Nearby is the joint plot of LGBT activists Barbara Gittings and Kay Lahusen, partners in work and life. During the 1970s, Gittings, who died in 2007, campaigned tirelessly to have homosexuality struck from the list of mental illnesses. Lahusen, a photojournalist who worked with Gittings on the first national lesbian publication in the 60s, is still going strong at the age of 86. But when the time comes, she will be laid beside Gittings in the LGBT corner.

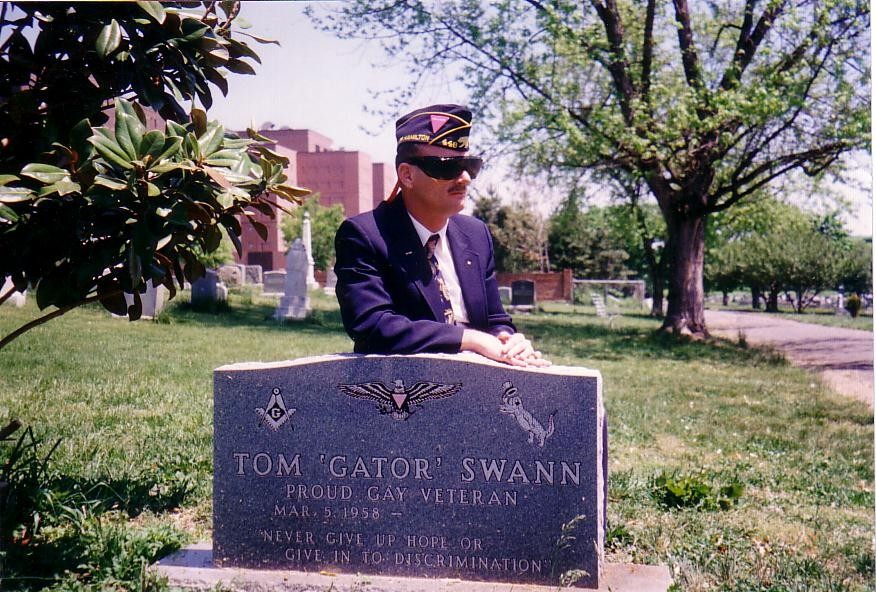

The headstone in the shape of a precariously balanced, jaunty black cube belongs to Ken Dresser, a gay graphic designer who worked on Disneyland’s Main Street Electric Parade. (“We encourage creative headstones,” says Williams.) Tom “Gator” Swann’s grave is marked by a headstone that reads “Never give up hope or give into discrimination.” Swann himself, a blind veteran and civil rights campaigner since the ’70s, is very much alive, but he made sure to purchase a plot early to secure his place in the LGBT corner.

Tom Swann stands behind his own headstone.

Though its primary purpose is to honor the dead, Congressional’s LGBT corner has become an inspiring gathering place for the living, too, with Matlovich’s grave forming the shrine-like centerpiece.

And there is a wedding or two among the funerals—in 2011, gay Iraq veteran Stephen Hill married his partner Josh Snyder—legally—in front of Matlovich’s memorial.

Update (3/30): The story originally stated erroneously that Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings are buried beneath their memorials.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook