The ‘Oscars Of Water’ Honors the Best of Bottled and Tap

A lithograph from the 1880s advertising Berkeley Springs as a tourist destination. (Photo: Jeanne Mozier)

The Oscars are upon us, but it’s not just movies that are being lauded. This weekend marks the 26th annual Berkeley Springs International Water Tasting—the self-proclaimed “Oscars of water.” Over 100 entrants, both corporate and municipal, will compete for the titles of Best Tap Water, Best Purified Drinking Water, and Best Bottled Water (Still and Sparkling).

While it may not have an E! red-carpet pre-show, the event in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia, has become the longest running and most prestigious water tasting competition in the world, attracting participants from around the globe. Bottled water companies have actually redesigned their labels solely to include accolades from the competition.

An example of a water bottle that redesigned its label to include a winning seal from the Berkeley Springs Water Tasting. (Photo: Jeanne Mozier)

And yet for all its industry prestige, the water tasting was never meant to be an industry event. What has become perhaps the most famous example of America’s obsession with bottled water was born out of a desire to bring visitors back to a town that was built off of another American obsession with water—mineral springs and their associated spa towns.

When Jeanne Mozier moved to Berkeley Springs in the 1970s, there wasn’t much to distinguish the community of about 600 residents from any other small town in the state. Berkeley Springs isn’t located on a river, or any other major thoroughfare. Though just an hour-and-a-half from Washington, D.C., the town had been on the decline in recent decades, with the economy largely dependent on a few local industries, like a tomato cannery and a small sand mine on the outskirts of town.

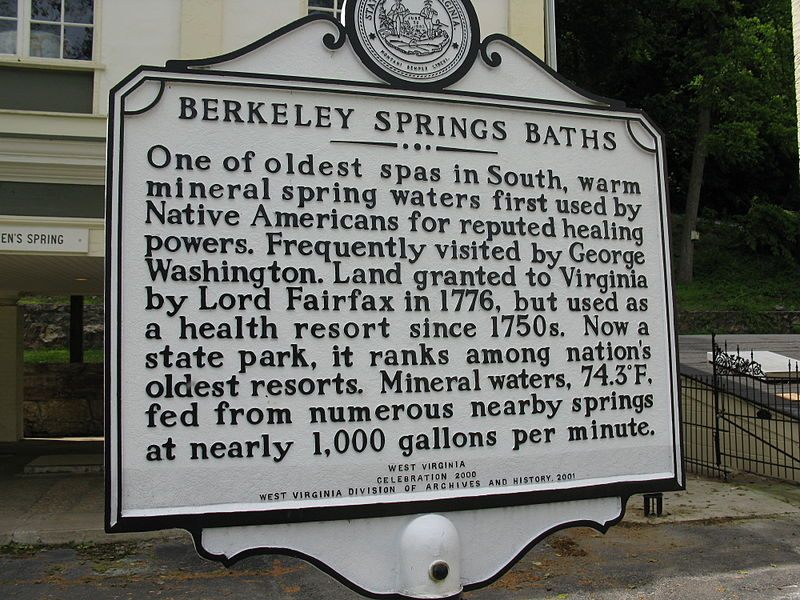

But Berkeley Springs had one thing going for it that other West Virginia hamlets didn’t: a mineral spring in the center of town. And this was no ordinary mineral spring. It flowed at a constant 74.3 degrees Fahrenheit, happened to be one of George Washington’s favorite vacation spots, and inspired the United States’ first spa town.

A sign for the Berkeley Springs Baths in West Virginia. (Photo: Andrew Bossi/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.5)

In the 18th century, scientific advances like Louis Pasteur’s theory of germs had sparked a renewed interest in bathing and personal hygiene. By the 19th century, Europeans were visiting spa towns like Bath en masse, to treat afflictions like rheumatism, gout, arthritis, infertility, or skin issues.

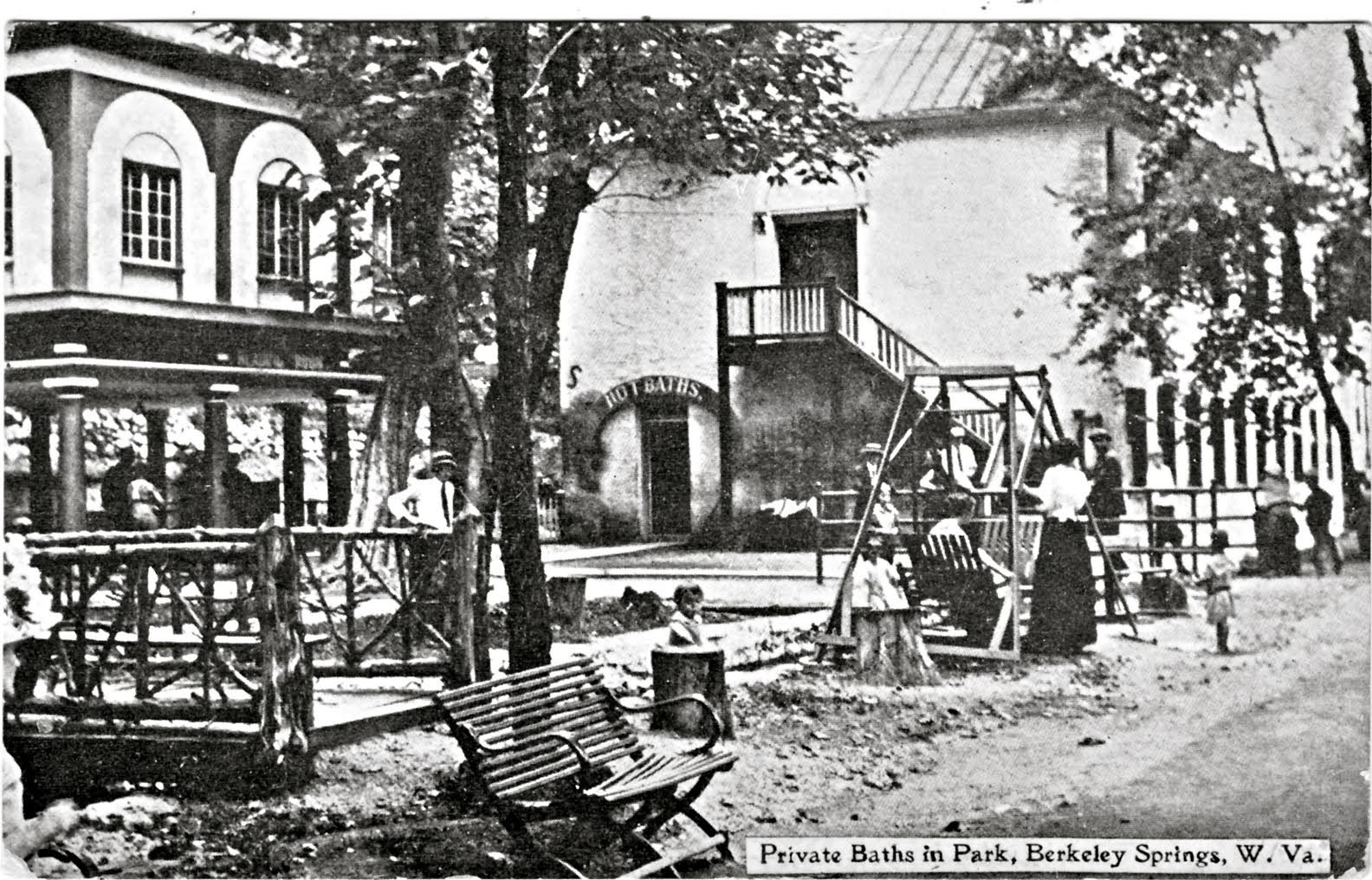

Berkeley Springs, founded in 1776, was the first iteration of a European spa town in the United States. Like in Europe, American spa towns thrived off of their reputation for wellness. Hydrotherapy, the catch-all for taking mineral waters, was looked at as a medical panacea. By the 1850s, more than 20 of the country’s 31 states had spa towns, with an increasingly sophisticated network of resorts catering to all kinds of leisure activities, from swimming to hunting.

A photograph of the mineral spring and baths circa 1900. (Photo: Jeanne Mozier)

For Berkeley Springs, the late 1800s were somewhat of a golden age, and the town saw a marked increase in visitors looking to spend their spring and summer months enjoying the town’s waters. A series of devastating fires hit the town in the early 1900s, however, wiping out both of the town’s hotels and putting a serious dent in its ability to attract tourists.

Those fires coincided with a general downturn in the popularity of water cures across America, due in part to advances in medicine (like the advent of antibiotics) and an expansion of the American transportation system, which opened up new places for Americans to vacation. Some former spa towns, like Palm Springs in California or Saratoga Springs in New York, were able to successfully make the transition from destination spa towns to self-sustaining cities, but for towns like Berkeley Springs, the decline of the American spa town marked the beginning of a decades-long slump.

Just as the nation’s spa towns were losing their grasp on the public imagination, the bottled water industry was finding its first foothold. In 1859, the Ricker family, based out of Maine, made the first commercial sale of water bottled from a mineral spring on their property, extolling the health benefits of the water. In 1907, they opened a commercial bottling plant near the spring, a facility that would eventually become the headquarters for Poland Springs. Two years earlier, hoping to mirror the success of the Ricker family’s bottled water operation, Dr. Alvah Jackson began selling water bottled from the Eureka Springs in Arkansas. Jackson’s business, which would eventually become the Ozarka Spring Water Company, also promoted its waters on the basis of their special healing properties.

The mineral spring and baths today. (Photo: Jeanne Mozier)

The bottled water industry didn’t really get going, however, until the 1990s, when marketers spent millions of dollars a year to present the product as a pure, natural alternative to industrial, sugary soda. This brings us back to Berkeley Springs, and the origins of the “water Oscars.” At the time, Jeanne Mozier had been working with Berkeley Springs’ other young, formerly urban newcomers to revitalize what was once one of America’s premier spa destinations, bringing in restaurants, attracting artists, and restoring historic movie theaters. But convincing people to visit in winter was difficult. Then, in 1990, the Berkeley Springs tourism council had an out-there idea for increasing visitor numbers.

“Someone had read a story in a magazine about a water tasting,” Mozier says. “Needless to say, everybody laughed at that idea, but we went ahead and did it anyway.” The competition has run every year since, and now attracts entrants from as far afield as Brazil, China, and Macedonia. While a panel of distinguished judges conducts the tasting for award-giving purposes, the public is also welcome to sample the many varieties of water. For those who can’t be there in person, the Berkeley Springs YouTube channel will stream this year’s event live.

Judges taste water at the annual Berkeley Springs Water Tasting competition. (Photo: Jeanne Mozier)

What started as an event based on the pleasures of water as a commodity has, in recent years, become a window into just how precious a resource clean water really is. In 2014, the competition took place as thousands in West Virginia dealt with tainted tap water from the Elk River chemical spill. This year, judges will crown the world’s best bottled water as residents of Flint, Michigan contend with levels of lead in their water so high that filters have been rendered useless.

“At some future time, being able to live in a town where you have access to pure water is going to be a phenomenal resource,” Mozier says. “There are certainly potential catastrophes down the road if people don’t wake up and protect the water.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook