The Visual Heritage of Westeros

Sigils have a long history in the land of ice and fire.

The Song of Ice and Fire series predated its HBO adaptation by about fifteen years, and, in that time, readers conjured up the entire world themselves, drawing on the rich detail and vivid descriptions provided by author George R. R. Martin. Now, an enhanced edition of Martin’s third book, A Storm of Swords, has been newly released on iBooks, including annotations, family trees, and interactive maps—as well as a deep-dive into the symbolism of every house’s sigil.

But the real art that helped inspire Martin and has laid the foundation for generations of fantasy worlds—rich as it already is with symbolism—is intriguing in its own right, and has just as much symbolism. In creating the Seven Kingdoms, their peoples, their monsters, and their rules and rituals, Martin drew on both an established fantasy canon and the visual heritage of medieval Europe.

Martin has cited the Tudor Wars of the Roses—and its two rival branches of the House Platagenet, House York and House Lancaster—as an influence for his conflict among houses for the Iron Throne. House York, symbolized by the white rose, eventually fell to House Lancaster, associated with the red rose, and the resulting Tudor dynasty ruled England for almost 120 years.

Scheming advisors, sick or ineffective kings, rival claimants, dashing young princes whose lives were cut short: some of the inspiration is general, but in particular, Martin seized on the device of the sigil (or crest) as a shortcut to identifying characters, much the same way heraldry and coats of arms were used in history. Wolves, lions, stags, and falcons all carry multiple meanings as well. In A Song of Ice and Fire, for example, not only does the direwolf flag show where House Stark holds territory and has supporters, the appearance of the wolf in dreams and prophecies acts as a metaphor for events in the past and hints to what may come in the future. Direwolves are small in number and native to the North—just like the Starks.

Sigils were a serious affair in history as well, like in medieval Europe, where these symbols showed where someone’s loyalty lay and guaranteed the identity of a message sender or recipient. Take this image, dating back to the 1600s, which is the heraldry of the German Huesst family.

Here, the coat of arms is hand-drawn in a “Liber amicorum” (literal definition: book of friends), which belonged to Joannes Erlenwien, a seminary student. His friends signed his “yearbook” with their family heraldry, just like high school students doodle and write notes in contemporary yearbooks. From this image we can learn a lot about the Huesst family: The black background indicates constancy, and the silver “X” shape (known as a “saltire”) symbolizes sincerity and suffering for faith. The helmet atop the escutcheon is barred, showing the Huessts were members of the nobility, and the human head most likely represents the patron saint of the Huessts’ home town. Compare that now to a Westerosi sigil like House Bolton’s (which depicts a flayed man on a blood-red field), and you begin to understand both the family’s violent predilections—and Martin’s point of inspiration.

Elsewhere in the Martin universe are the Riverlands and the Twins, the family seat of House Frey (sigil: two towers connected by a bridge), an important river crossing in the middle of Westeros and the site of much of the military action in A Storm of Swords. And, here, this print of a castle in the Netherlands overlooking a much-trafficked bridge comes close to what the Twins and the Riverlands might look like. Notice the many boats, signifying trade and commerce, the mill with waterwheel, the church in the left middle-ground, and how the bridge acts as a choke point between the two sides of the river.

After a battle’s end, the losers often find themselves at Harrenhal, the cursed castle visited so far by Arya Stark, Gendry Waters, Roose Bolton, Jaime Lannister and Brienne of Tarth in A Storm of Swords, and who knows what unlucky souls in the future. The largest castle in Westeros, and holding some of the richest lands, Harrenhal was a formidable place before its ruin. Don’t mind the man sleeping in the foreground in this Italian print: the castle depicted is a scary place! The sun is rising to the east, but the castle is still shrouded in cloud cover and moonlight. There’s an ominous, cave-like passage at the base of the castle, one of the towers is ruined, and the trees surrounding it bend low, as if they’re dying. At Harrenhal, Jaime loses his sword hand, and Brienne is almost killed. Were it not for Jaime’s dream (we can almost imagine it is Jaime, asleep in the foreground), he would never have returned to Harrenhal and brought Brienne to safety.

And all Westerosi little boys and girls know what destroyed Harrenhal:

Dragons.

The dragons in this 16th century print don’t appear to breathe fire, but the severed head (including exposed windpipe) in the foreground and those gruesome talons—and the fact that the dragon is depicted in the act of eating a man’s face—suggest that these dragons would be right at home with Drogon, Rhaegal and Viserion. This particular dragon is the Ismenian Dragon, which in Greek mythology guarded a spring near Thebes dedicated to Ares until it was killed by Cadmus. Dragons are often depicted guarding treasure, valuables and sacred places, and only occasionally do they breathe fire (a trait that became more common in medieval folklore).

So, how would someone with a dragon fascination of leviathan proportions find such a beast? Despite the expression “here be dragons” being associated with the whimsical imaginations of medieval cartographers, there is no evidence that these words were ever included on a flat map from that era. The Latin phrase does, however, seem to originate from the early 16th-century, where it appeared on what is now known as the Hunt–Lenox Globe.

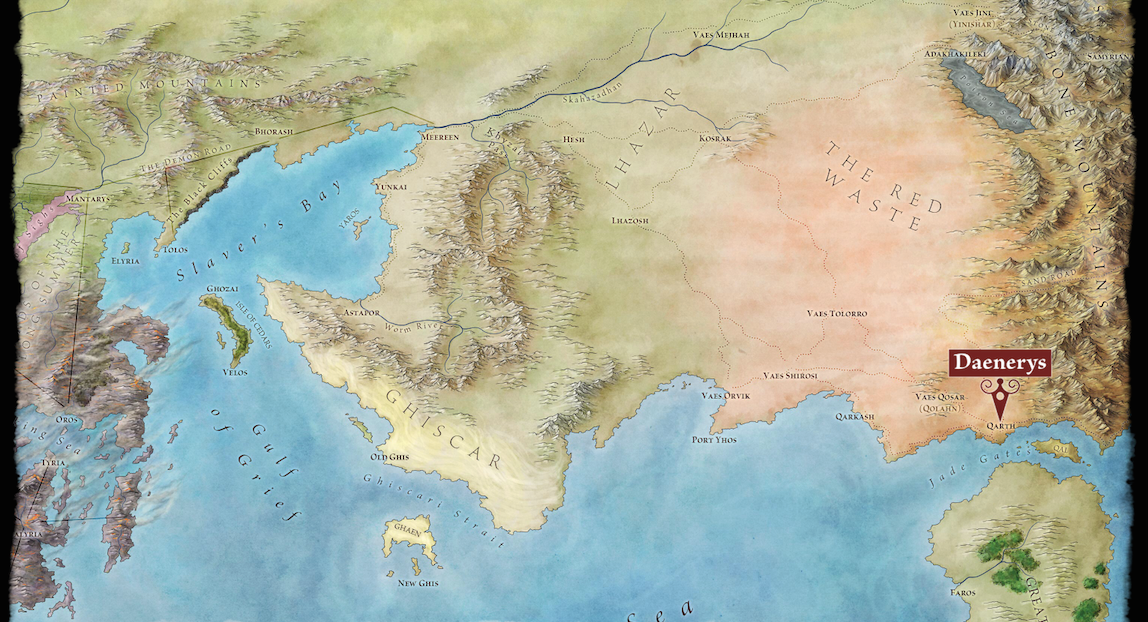

While it might have taken a lot for a medieval sailor to find a map that would have directed him toward dragons, all an adventurous Westerosi would have to do is head east, across the Narrow Sea and around the cape of Valyria, to where Daenerys Stormborn raised her brood. That is, after all, where dragons—and their mother—be.

Explore the enhanced digital edition of George R.R. Martin’s A Storm of Swords with Atlas Obscura on iBooks.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook