The Rise of the Luxurious Suburban Master Bathroom

How a utilitarian room turned into a pleasure palace.

The 1986 edition of the International Collection of Interior Design, a trade magazine for those in the business, issued a bold statement regarding bathrooms:

“The era of the utilitarian, puritanical bathroom is over and now it is returning to center stage as the place for luxurious, sophisticated relaxation in the home.”

The 1986 bathroom would bring back the grand indulgences of the Romans, who surrounded themselves with plush beauty during their ablutions. This elevation of the master bathroom from the “necessary room” as it was euphemistically called, to its reign as the cornerstone of the master suite, was such a rapid and recent development, that it is easy to take it for granted.

Bathrooms haven’t changed much since indoor plumbing became a standard feature in newly built homes at the turn of the 20th century. This, coupled with changing societal expectations regarding the frequency of bathing and new technology such as the flush toilet, swiftly ushered in the era of the modern bathroom.

Indoor plumbing coincided with the discovery of germ theory—the idea that disease is spread by germs. More importantly, germ theory linked cleanliness to the prevention of illness. The intersection of science, technology, and societal pressures for cleanliness ultimately led to the development of the “hygienic” bathroom—one clad in tile and other hard surfaces, absent of carpet, heavy drapery, or other porous soft goods thought to be good places for germs to fester. The easier a bathroom was to clean, the more proper, safe, and sanitary it (and the people who used it) was.

The hygienic prototype, aided by the new marvels of mass production, swiftly became and remained the standard. The typical bathroom is a five-foot-by-eight-foot square room with a bathtub, a toilet, and a pedestal sink. The pedestal sink may be swapped out with a vanity sink, the bathtub with a tub/shower combo or a shower stall, but the basic composition of three porcelain fixtures in a small room has remained relatively unchanged throughout the decades.

The consistent design schema of bathrooms is linked to a number of factors. Ease of cleaning was the main appeal in bathroom design—hence the popularity of tile walls and floors, as well as porcelain fixtures. The vanity sink, for example, did not become popular until the 1950s, when new materials such as formica and MDF made them less expensive as well as easier to clean and maintain.

In addition, Americans have always had a difficult time talking about intimate matters, including bathroom activities. The impropriety of such dirty acts as passing bowel movements made the bathroom a place that remained out of sight and out of mind, clinical in its aesthetic and unchanged since its inception. A recent article for The Atlantic pointed out that discussing or depicting the bathroom (specifically the toilet) on television was considered obscene until as late as the 1970s.

House size, however, was the main concern. At the turn of the 20th century, the vast majority of Americans lived in cities, and dwelled in townhouses, apartments or tenements. With the availability of mass-produced housing and inventions such as the streetcar, more affluent families expanded into the first generation of suburbs, located within the outer limits of the city.

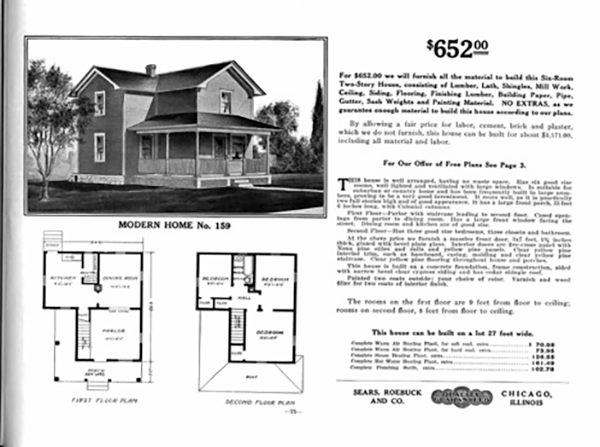

The first generation of these houses, built from the 1890s to the early 1920s, took after farmhouses and Queen-Anne-style architecture, were the largest of the kit-houses, boasting 3 or more bedrooms as well as a parlor for entertaining. Still, despite their size, very few had more than one bathroom, as bathrooms were still rather expensive to build in the days before the fixtures could be cheaply mass-produced.

The majority of the kit houses from the ’20s and ’30s (which made up most of the U.S.’s suburban stock) were bungalows—small, one-story houses boasting two or three bedrooms and a single bath.

The bathroom was a utilitarian place, and its aesthetics came secondary to its functionality. There was no need for a large bathroom or multiple bathrooms in early suburban life, as space was scarce and fixtures were expensive. The Great Depression and World War II stalled residential construction, creating a huge need for housing in the 1940s. Coupled with the invention and proliferation of cars and housing incentives provided for veterans through the GI Bill, modern tract suburbia was born.

Despite the incentives to buy, the GI Bill only covered housing which conformed to the guidelines set by the Federal Housing Authority’s mandates: a price range of US$8,000 to US$10,000 and a size range of 800 to 1,000 square feet. Thus, houses built in 1950 were even smaller than those built in the previous 30 years, boasting a mere two or three bedrooms, a kitchenette, and one bathroom. These houses also boasted an open floor-plan in order to make them feel much less cramped than they actually were. Families sacrificed privacy for comfort.

However, it was during the 1950s that new and exciting technologies came on the market for the bathroom: hairdryers, built-in ventilation fans, warming units, and a plethora of new catchy products for haircare and makeup.

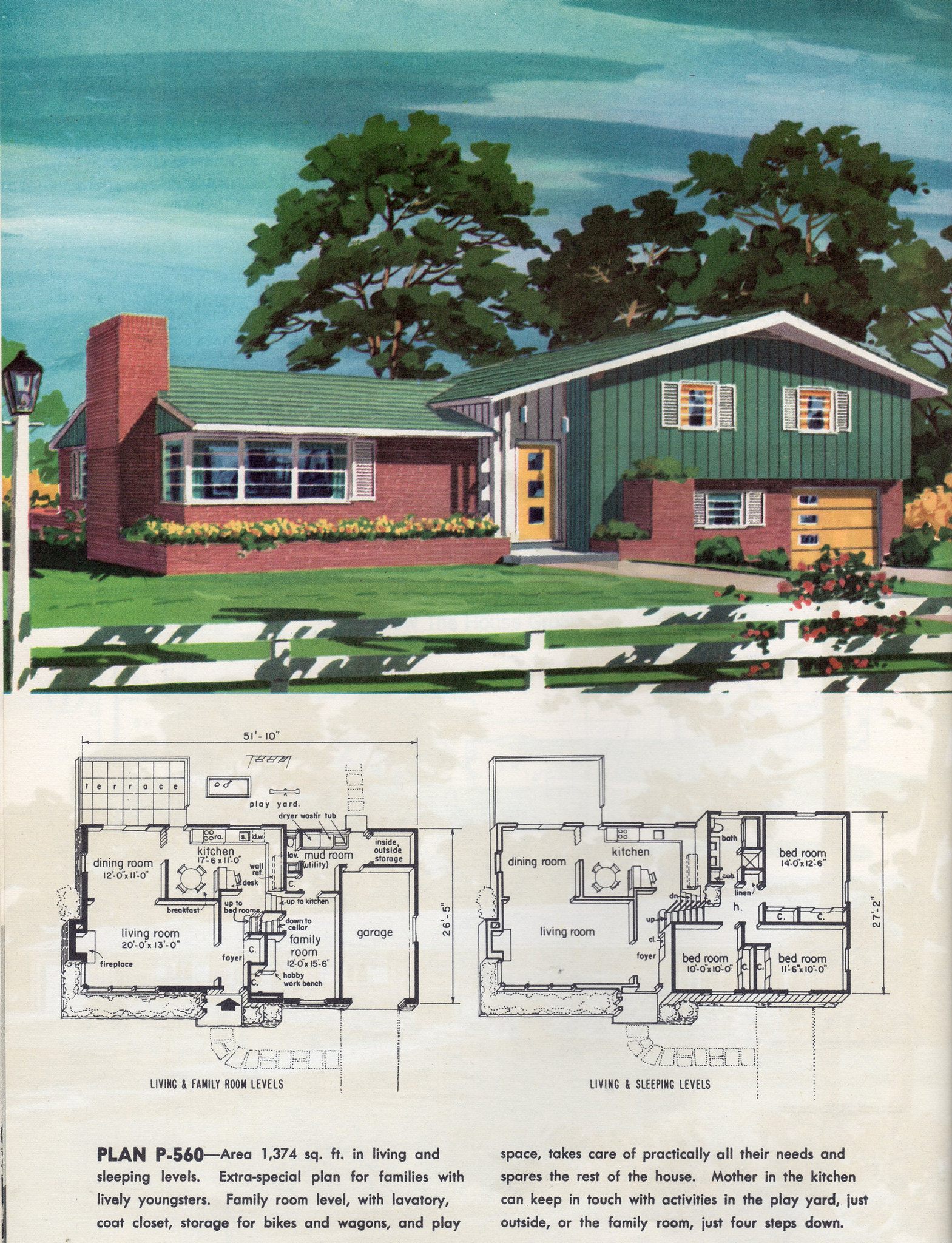

All of these new gadgets required space, and Americans wanted bigger and more spacious houses, especially since the two-car attached garage was becoming more and more common and desired. A garage was a huge chunk of square-footage, and house size grew accordingly.

The ’60s and ’70s saw further expansion out of cities into rural areas, and house size increased due to the inexpensiveness of rural land.

More square-footage meant more luxury. For example, standard queen- and king-sized beds didn’t even exist until the end of the ’50s. In response, the bathroom, for the first time in decades, had begun to change. The biggest change was the dawn of the commonplace master bath. House size was only one factor that facilitated this new luxurious feature.

Newly constructed neighborhoods featured infrastructure for more efficient plumbing and water management, leading to an increase in bathrooms in the home. Gone were the days when flushing the toilet meant a scalding surprise. More space meant that unlike their FHA-mandated predecessors, new houses boasted less-open floor-plans, offering the marital couple privacy. In addition, the sexual revolution of the ’60s led to more open-mindedness about private matters, as well as a penchant for plush new features like jacuzzis and garden tubs.

These factors stuck with the American public, and the master bathroom took off, becoming standard on all new homes by 1980. However, these bathrooms were still rather modest, like the one above.

The growth of houses, while generally on the increase since 1960, stalled in the ’70s due to an energy crisis. When the ’80s rolled around and energy became cheap again, there was an explosion in homebuilding, and the homes kept getting bigger and bigger. The introduction of new construction materials (e.g. vinyl siding) and relaxed mortgage lending practices in the ’80s and ’90s meant it was easier to get a bigger house for less money. The outsourcing of labor during the Reagan and Clinton eras made consumer goods less expensive, and Americans consumed new goods—including luxury goods now available at a lower price point—like never before. Thus, the master bath exploded.

Societal changes have played a role in the growth of the master as well: women entering the mainstream workforce and the rise of the working couple meant families earned more, had more stuff, and needed more space. The puritan notions of the bathroom as a dirty place no one talked about were over—now was the time for sunken tubs and flaunted luxury.

The story of the master bathroom was long in the making. A space we now deem a necessity is only around 36 years old. It’s one of many examples of how a cocktail of social, technological, and economic influences combine to create new standards of living, and change the face of not only architecture, but how we live.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook