The Resurrection of Rajasthan’s Royal Liquors

After fading away post-Independence, Heritage Liquors are back and, this time, everyone can sip them.

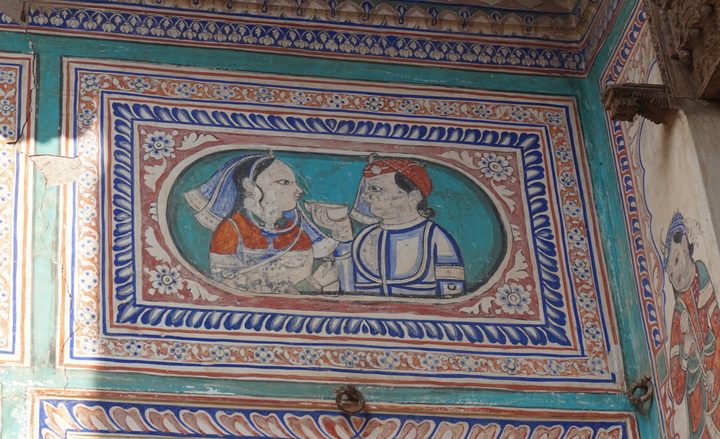

Maharani Mahansar Heritage Liquor is the modern manifestation of a nine-generation family tradition that has spanned monarchy, colonization, and independence in India’s northern state of Rajasthan. The Shekhawat family, descended from a prominent baron—or thikanedar—of Jaipur State in the early 1700s, began distilling liquor in 1768. Now, for the first time since Indian independence, the family has returned to distilling old recipes in their ancestral village of Mahansar. Not only do these heritage liquors contain the spiced aromas of India, they also hold lessons in the history of power in Rajasthan.

The earliest renditions of Rajasthan’s liquors would not have been liquors at all, but fermented herbal infusions used for dosing Ayurvedic natural medicines called asava. But by the 15th and 16th centuries, Rajasthan’s ruling class was largely from the Rajput caste system, which allowed drinking alcohol (whereas elites in other regions were often of the Brahmin caste, which discouraged the practice). As a result, royal physicians who served the local maharajas concocted new herbaceous medicines in high-proof spirits, which they came to call asaav. Reserved only for the ruling class, intriguing medicinal recipes called for potent ingredients like mutton, rabbit’s blood, and fluid from the skulls of male sparrows.

As distinct liquors emerged, the operation of darukhana, or distilleries, was outsourced to a class of feudal lords known as jagirdars and thikanedars. Surendra Pratap Singh Shekhawat’s ancestors were among these noble distillers to the kings. “It was quite old and traditional, using clay pots and fermenting with ingredients like jaggery,” says Shekhawat, who now serves as managing director of the Shekhawati Heritage Herbal private distillery, which makes Maharani Mansar’s liquor. “You add your different ingredients depending on your recipe and you ferment it for so many days, and then you distill it, and you distill it again, and you distill it again to bring out the finest form of liquor.” Only then was it ready for the royal families. In Mahansar, his family produced spirits on behalf of rulers in Bikaner, Jaipur, Jodhpur, and Jaisalmer (and kept some for themselves).

The spirits they distilled would have had concentrations of alcohol that rival today’s absinthe, around 80 percent. Tales suggest that a cotton ball dipped in the liquor could get anyone drunk. According to Anil K. Singh, the former general manager of Rajasthan’s official state-run distillery and author of a forthcoming book on Heritage Liquors, the recipes ranged from a minimum of 20 to over 75 herbs and spices. These flavors encompassed traditional Indian staples like cardamom and fennel as well as more distinct aromatics such as safed musli root and sandalwood.

It helped that the maharajas were ruling over a land through which the Silk Road passed. Magan Singh, author of The Indian Spirit, argues, “Just the fact that you had access to these spices meant that you were rich.” As an example, he cites Kesar Kasturi, a liquor made for the Jodhpur royal family from the extravagant combination of saffron and the waxy secretion of the Himalayan musk deer. “Saffron didn’t grow anywhere in Rajasthan, it came all the way from Kashmir, a journey of a month. So it’s the most lavish thing,” he says. The power of the maharajas was distilled in these spirits, which represented luxury, exclusivity, and a total control of policy. But that began to change when the British colonized South Asia.

It was British colonization that led to the popularization of distilled spirits as recreational beverages throughout India. In the late 19th century, the British government implemented several policies that punished those who produced traditional fermented beverages and consolidated the alcohol market in the hands of licensed government distilleries who produced what would come to be called Indian Made Foreign Liquor. Moreover, common Indian recreational products like cannabis and opium were frowned upon by the British, while alcohol was permitted. Wealthy Indians who worked alongside the British learned to drink spirits as they did—often in the form of whiskey, rum, and gin.

But even asaavs, once medicinal and aphrodisiacal elixirs restricted to royals, were becoming consumer goods. Raj Shree Thakur Durjan Saal Singh Ji, of the Shekhawat family, began commercial distillation in 1890. Commercial distillation also meant industrialization. According to Anil Singh, a Jodhpur distillery opened in 1924 with machinery imported from Glasgow. “It was a modern distillery,” he says. “Before that, all liquors were made on local traditional processes using firewood and all.”

This moment, though, was short-lived.

After India gained independence in 1947, Mahatma Gandhi’s anti-alcohol beliefs began to influence policy. In the Directive Principles of the Indian Constitution (which are not law but are meant to guide states in their governance), prohibition was strongly encouraged, though alcohol was ultimately left for each state to regulate. In 1950, the new democratic state government of Rajasthan implemented the Rajasthan Excise Act, which reset the licenses and laws that governed local distilling.

With independence, the royal families and the thikanedars could no longer control the alcohol industry. “They were banned,” explains Shekhawat. “At that time, our projects and distilleries were also shut down.” With the power outside of the hands of those who traditionally consumed the liquor, it quickly disappeared.

That is, until the new democratic government began to distill commercially. During the 1950s, the Rajasthani government opened a state-run distillery. The state-owned sugar mill used molasses from their production to ferment and distill “country liquor,” which could be distributed only within the state.

For almost 50 years, heritage liquors disappeared altogether until one maharaja, High Highness Gaj Singh Ji Sahib of Jodhpur, pushed for the reestablishment of the traditional asaav under the new name “Heritage Liquor.” On July 9, 1998, the Heritage Liquor Act amended the Rajasthan Excise Act to include a new, permitted category for the royal spirits in hopes of drawing in revenue from the region’s history. The act opened up proposals for new distilleries that were run by families with a tradition of making herbal spirits.

Shekhawat says that royal families had regularly been suggesting that heritage liquor be reinstated since they lost their license in 1950. When the Heritage Liquor Act passed, the Shekhawats of Mahansar were able to re-enter the world of traditional spirits.

To get the license, the family had to show the government their recipes, for around 150 liquors, written in old Rajasthani dialect that only elders could read. After getting approved, they first produced their liquors in other facilities until 2020 when they built their own distillery in Mahansar. Now, under their own roof, they produce liquors with saunf, or fennel, Damask rose petals, cardamom, orange, paan leaf, and other aromatic herbs. Their reputation has spread. “If you say Mahansar, people know that we make liquor,” Shekhawat says.

The state-owned distillery has also moved in on the Heritage Liquor category. They’ve worked with Jodhpur’s maharaja to produce recipes like Kesar Kasturi and Royal Jagmohan, the latter of which includes saffron, barks, and fruit preserves called murabba mixed with milk and clarified butter among other things. Meanwhile, an aristocratic family of Kanota gave the state distillery their recipe for Chandr Hass, a drink they used to produce as thikanedars of Jaipur, with over 80 ingredients like sandalwood, nutmeg, and dried fruits. Anil Singh says that, for these families, profit isn’t the point; their main goal is to ensure “their recipes are safe from dying.”

Even so, now that heritage liquor is regulated by the democratic state, some things have changed. Where the liquors were once reserved for royalty, distilleries are now marketing to the public. Their legendary strength has been watered down to around 40 percent alcohol by volume due to regulations. Ingredients, too, have changed due to various issues like Indian narcotics law, the 1972 Wildlife Protection Act (which banned the use of musk deer secretions), and the affordability of rare spices.

“Today what remains of the royal liquors—I think it’s a fraction of what they were originally drinking,” Magan Singh says. “The distillation process would have been less fine-tuned, but it would have had more texture to it—more of everything. They could have done anything they wanted. If someone said you had to distill this through gold brocade, the kings would have made it happen.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook